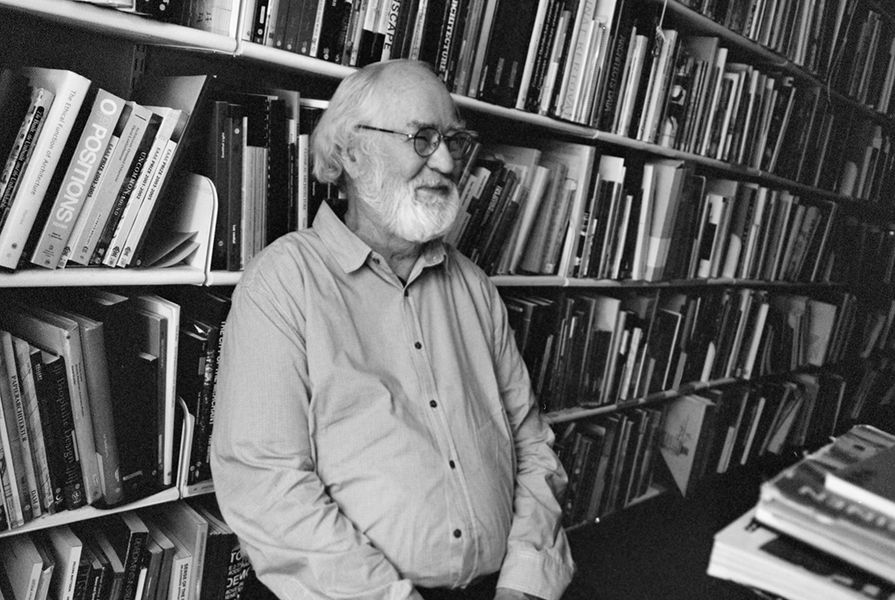

Finnish architect and theorist Juhani Pallasmaa took part in the Droga Architect in Residence program in 2016.

Over the more than 50 years that Pallasmaa has practised architecture, his interests have shifted from rationalism, standardization and prefabrication to phenomenology, culture and neuroscience. While in Australia he ran workshops with students and delivered six lectures in different cities on topics including “Dwelling in time – the architectural meaning of time,” “Tradition and Newness – continuity and meaning in art” and “In Praise Of Vagueness – diffuse perception and uncertain thought.”

In this interview, the first in a series of interviews with past Droga architects in residence, Pallasmaa discusses the value of architect residency programs, the problems with architecture and modernity and some unlikely sources of inspiration, from dance to neuroscience.

Josh Harris: Your residency was four years ago, so I understand if some of the details are a bit vague, but could you give brief sketch of what your memory of the residency was? How was the experience for you?

Juhani Pallasmaa: I was there with my wife, Hannele, who’s a retired journalist, and my memories of the months in Sydney are extremely positive.

Partly because I had been to Australia several times before, and I already had a number of friends among the best architects in Australia. I had been in similarly privileged situations at the American Academy in Rome, and the Frank Lloyd Wright Taliesin West studio in Arizona, so I was prepared mentally, but altogether the time was very enjoyable, both in terms of the connections and program I had there, my six lectures in various museums, and then also in terms of my own work. I wrote a number of essays and I also worked on a book. I always work; even though I’m now 84, I still write 10 hours every day. And of course, the Droga Apartment was very enjoyable and beautifully located in relation to Sydney. My lectures outside of Sydney gave me a chance to see different parts of Australia. I had already earlier visited the Kakadu National Park and Tasmania.

JH: You mentioned that you gave six lectures, and I understand that you were inspired by Harvard University’s Charles Eliot Norton lecture series, which featured writers such as T.S. Eliot and Italo Calvino. What was it about the six-lecture format that appealed to you?

JP: The choice of six lectures was not mine, it was decided by the people at the Australian Institute of Architects Foundation, who selected the locations of my lectures, but the fact that I had six lectures appealed to me. Due to the influence of my professor and mentor Aulis Blomstedt, who studied proportional systems passionately, I have been a Pythagorean since the late 1950s. I like certain even numbers such as four, six and 12. In 2012, I wrote a book together with the American professor Robert McCarter, which is entitled Understanding Architecture. As we were planning its structure, we ended with 11 chapters. I said to Robert, as a Pythagorean, I can’t deal with number 11, we have to have 12. We finally came up with the 12th theme and then the whole concept became very clear. The entity of 12 themes divides beautifully into two or three, four or six logical groups of titles, or themes. I tend to apply Pythagorean number harmonics to everything I do.

JH: In your first lecture in Sydney, you spoke about atmosphere and mood. I know you’ve said that artists and musicians are more aware of atmosphere than architects. Why do you think that is?

JP: Modern architecture in particular has been focused, or even obsessed, with form. On the other hand, atmosphere has not much to do with form. Forms impress us through their fixed qualities. Also, modern architecture has been oriented towards focused perception, focused form, whereas atmosphere is a peripheral, immaterial and largely unconscious perception. Atmosphere is against the grain of contemporary architectural thinking, and most architects would – at least they would have 20 years ago – considered atmosphere a somewhat romantic notion, which should be left to stage designers and window decorators. But during the past two decades there has been an increasing interest in atmospheres, which also implies that there is a growing interest in multisensory experience, as opposed to the singular visual experience.

JH: You had a public conversation with Glenn Murcutt during your residency. I know you’ve described him as one of the best atmospheric architects. What makes a good atmospheric architect?

JP: Well, in the case of Glenn Murcutt, my argument that his work is atmospheric might come as a surprise, because many would consider him a formal architect with a strong technological emphasis. But his love and interest in nature and natural phenomena is so strong that it penetrates even into the technological aspects of his architecture. Atmosphere arises from a dialog between the building and its setting, landscape and the climate, cultural context and traditions, etc. This is another criticism I have about modern and contemporary architecture, they tend to be a monologue. Maurice Merleau-Ponty has a thought-provoking line: “We come not to see the work, but the world according to the work”. This is especially true in architecture; architecture is fundamentally a mediating and dialogical art form.

I believe in architecture that is relational and which is in a dialog with history, time, setting, existing buildings, and life in general. I think that this is the essence of architecture; its relational and mediating nature.

JH: I’m interested in what you say about time in particular. You’ve quoted Italo Calvino in saying that time was destroyed in the modern novel. David Harvey has said similar things in the field of political philosophy, and you say that this is the case in architecture, that the time has been taken out of architecture.

JP: Well, it has not been taken out entirely, but the understanding of time and its focus has changed. Contemporary architecture is about now-ness – the depth dimension and the temporal interplays have been lost. And it is the now-ness in contemporary architecture that makes it emotionally flat, experientially and existentially flat.

I’m just writing a piece on the Swedish architect, Sigurd Lewerentz, and he’s one of the rare exceptions in modernity, whose architecture is not fundamentally visual but tactile. And it is also an architecture that speaks strongly about time – time as a durational presence rather than time as a kind of a historical chronology. His architecture is about silence, solitude and time.

JH: How can architects embrace the past and grapple with tradition without becoming regressive traditionalists? How does that dialog work in a way that’s not regressive?

JP: Historic influences do not only travel one way from the past to the future, they also travel the other way. I often use the example of Aldo van Eyck, the Dutch structuralist architect. When he was appointed professor at the University of Delft, the chancellor, who was his friend, asked him to give his inaugural lecture on Giotto’s influence on Paul Cézanne. Aldo refused and gave his lecture on Cézanne’s influence on Giotto, who lived nearly 600 years earlier. I think this reversed history is often much more important – causality also goes against time, the way that new ideas or artistic ideas reveal new aspects of the past and old art. For me, our time in the arts is a presence rather than a chronology. I often advise my students to select their mentors carefully and I advise to select their mentors from dead artists, who might have might have died 500 years ago. It works beautifully in art and architecture, because artistic ideas and works do not age; they have a perpetual presence, mental presence. The nearly 30,000 years old cave paintings are as fresh and moving in our experience as any work of today.

The worksop at Robin Boyd’s Walsh Street house.

Image: Robin Boyd Foundation

JH: You’ve said that when you first started collecting books, you had “architecture” books and “other” books. But as you’ve as you’ve grown older, you’ve started to read more of the “other” books than the architecture books.

JP: Absolutely. My library began as a collection of architecture books, now it’s about 10,000 volumes, and for the last years, I have very rarely purchased an architecture book, simply because architecture books tend to be rather superficial and professionalist reports on the work of the architect. Novels, poems, biographies of great artists and books on the sciences open up for me more inspiring ideas and perspectives than books on architecture. This view results from the dialogical and mediating essence of the art form of architecture.

Books on philosophy, poetry, painting or sciences tend to get into the essence of things in a manner that inspires me. One of the latest books I have read was by a young Finnish astrophysicist on Cosmology and Dark Matter, and I was greatly inspired by the idea of dark matter. The new physics opens up truly novel ideas about space, time, matter and energy, for example.

JH: I know you’ve recently been interested in neuroscience as well, could you tell me how your study of neuroscience has informed your architecture critique?

JP: I have not really studied neuroscience. I have never academically studied philosophy either. But I read philosophy books constantly with satisfaction and inspiration.

Speaking of inspiration, when beginning a new project, I have practically never looked at projects of other architects in similar tasks. I mostly look at paintings, all the way from paintings of the Siena School, the early Renaissance painters, Piero della Francesca, Rembrandt, Vermeer, the Impressionists, the Abstract Expressionists, etc. These works of art do not give me any concrete examples of architecture, but they soften my mind and fill it with inspiration and optimism.

I have philosopher and neuroscience friends, just as I have painter and poet friends, and I read books in these fields because they inspire me.

I was drawn to neuroscience by a lecture invitation at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, where Louis Kahn designed a marvelous building, and after that I have been repeatedly invited to lecture and teach, at the New School of Architecture and Design in San Diego, which is probably the first architecture school to start a course in neuroscience and design.

So, I have been drawn into a continuous conversation. I have also had, for six years or so, correspondence with Michael Arbib, an American neuroscientist, who was educated in Australia and was a schoolmate of Richard Leplastrier. That’s the way I usually get involved, not seeking actively myself, but reacting to the occasions that open up.

I have also had conversations and contacts with dancers, but also they have sought me out because of my writings. Many times it has been very rewarding, because of the choreographic nature of architecture.

JH: I can certainly see parallels between your writing on architecture and the way that dancers might think about the way their bodies occupy and move in space. What did you talk about with the dancers?

JP: Well, very fundamentally, architecture is a choreography. Every piece of architecture choreographs human movements, behavior, observations, attentions, experiences and emotions. I have been very interested in the choreographic dimension in architecture, which is an active component in architecture. A window frame is not architecture, it is the view of a mountain far away, or of an apple tree in bloom in the garden, which is architecture. I have often said that architecture is a verb; I think this idea mediates the fact that architecture works on our behavior, from physical movement to mental and emotional movement. This was to some degree already written about by Charles Moore in the 60s, but it has not been studied further or brought to the educational context.

JH: So often architecture is spoken about as a being static, but you are located in a dialog, as a choreography rather than as a static object.

JP: Yes. I’m beginning with the fundamental idea of John Dewey: the artistic dimension does not exist in the painting, or a building as an object. The artistic component is a mental thing, it is in the personal and unique experience. Also in education, we teachers should more focus on how things are experienced than on conceptual or geometric or ideational intellectual criteria.

JH: What role does imagination have in architecture?

JP: Imagination is absolutely essential. Even our perceptions contain an imaginative component. We tend to think that perception is a well-defined event with boundaries. It’s not. Every percept is immediately connected with memory and projected to imagination. Every percept has this temporal continuum, we combine every percept with something that we have experienced before and we project it through our imagination to understand what might come out of it. Imagination is integrated into our way of experiencing the world. It’s not a separate category.

Now that I’m writing on Sigurd Lewerentz, I have been thinking about Gaston Bachelard’s idea that there are two imaginations: formal imagination and material imagination. He argues that images of matter are more emotional than images of form, which I fully agree with. Again, my criticism about the main line of modernity is that it operates with formal imagination rather than material imagination, with the exception of certain architects, Lewerentz being one of them. We also have empathic and ethical imaginations, which are central dimensions in the architectural imagination.

JH: Is it fair to say that you are rather pessimistic about the state of architecture, and where architecture is going?

JP: Yes. I have full confidence in the continued meaningfulness of architecture and the central mediating task of architecture in culture and human fate. I am critical about the current orientation of architecture, which is becoming increasingly a service profession, a prescribed service like the practice of engineering or law.

Also, architecture has become rather narrow-minded in terms of its dialogical relationship with history. Buildings are increasingly visual, most of them are visual exercises, which have very little relationship with the rest of the world. Architecture is turning into an aesthetic manipulation. We are made to experience someone else’s feelings, not our own.

I am critical of the situation of architecture in the market economy and consumer culture. I’m not pessimistic at all about architecture as a human and cultural device and manifestation. Architecture is absolutely essential, because it is part of ourselves. We extend ourselves into the world through architecture in a very central and significant manner. Without the art of architecture we are doomed back to barbarism.

JH: Do you connect this sort of problem with political economy, with capitalism?

JP: It’s everywhere – it’s in the legislation, in the ever more complex regulations concerning architecture, construction and planning. It’s also in the economic emphasis, in the dominance of the idea of profit in societies everywhere. I think now that real architectural qualities have nothing to do with the idea of profit. As I said earlier, they are mental things which celebrate culture and human potential.

I would also blame here architectural education. In most cases around the world I have witnessed the pressure of the commercial orientation, profitmaking and shallow professionalist orientation dominating. When I teach, and I have been privileged to teach around the world, I usually take tasks which are very close to art simply to push students to a territory that is not so familiar, to prevent students from considering architecture as prescribed professional answers. In real creative work, there are no questions. The answers and questions arise simultaneously, and you cannot distinguish the question from the answer.

I have never considered myself a professional. I have always had an overwhelming feeling of uncertainty, which is typical to an unprofessional. Uncertainty keeps you alert and perceptive.

JH: During your residency you run a workshop at the Robin Boyd house in Melbourne with some students from the University of Melbourne. What was that workshop?

JP: It was one of the workshops where I guided students to think through materials and not forms. Our task was to create the space of the Last Supper in an underground parking garage of the university. I told my students that you have to choose your materials, or a material, in the very beginning and then sketch with the material, work all the time with the chosen material. If you choose water, you have to sketch with water. If you choose fire, you have to sketch with fire. In fact, quite a number of the students chose fire, and I was a bit worried about having these small fires in the garden of the Robin Boyd House.

JH: That wouldn’t have been great if the Robin Boyd house had burnt down! Could you speak a little bit about the value of the Droga program and architect in residence programs in general, you mentioned you’ve been part of a number of these programs now.

JP: Well, I have very positive feelings about such programs all together. It is a completely different thing to be able to stay in a place for two, three, four months or half a year than stopping as a traveller. It is the prolonged stay that roots you momentarily in the place. For instance, as a repeatedly hurried visitor in Rome I had experience Rome as an arrogant city, but living three months in the middle of all of it, made me realize the combined humility and pride as well as the endless cultural richness of Rome. You see other things, you learn more, and then also the new relationships to other people and cultural patterns and habits; all of that is so important. I feel that I have grown intellectually and emotionally specifically during my repeated travels, and especially, my extended stays in different countries and cultures. As a young boy living at my grandfather’s humble farm during the war years of 1939-45, I often tried to imagine the world beyond the range of densely forested hills around the fields. Now, after my 108 rounds around the globe, I am beginning to know that world as a reality.