Russell Hall’s Windmills on Show at SQIT’s Toowoomba campus, built on the old showground site. Photograph Euan Kok.

Advertisement for the Economy Windmill, one of a range of windmills collected for the installation.

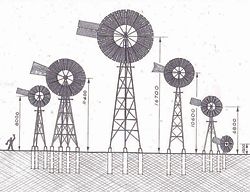

Elevation of Windmills on Show.

Windmills were collected from all over southern Queensland and reconstructed. Photographs Russell Hall.

Model of Russell Hall’s new windmill design – an asymmetrical steel tower with the pumping gear external to the framework. (In standard windmills the pumping gear obstructs access for maintenance.)

Russell Hall’s Windmills on Show at SQIT’s Toowoomba campus, built on the old showground site. Photograph Euan Kok.

I can’t say I know much about what happens behind the scenes in Queensland before something is accepted as public art – allowing it to appear safely on a footpath, or be attached to a building like a piece of costume jewellery. Nevertheless, I wholeheartedly support the idea that a percentage of building project budgets be allocated to providing more than mere utilitarian ends. In Queensland, the figure is two percent and the programme has been running for about ten years. All publicly funded projects have dutifully contributed to the effort. In our booming state, this translates into lots and lots of “art”.

Some is witty, captivating, inventive, appropriate and intelligent. In this category I would include Chris Trotter’s modest human-scale steel kangaroo, welded from machine parts, sitting on a municipal bench in George Street, inviting company. This piece depends on being discovered and exudes personality. It is certainly popular and memorable. Other “art pieces” are highly competent, well-finished professional renderings, somewhat low on imagination but part of the well-established genre of monumentalizing recognizable objects, generally in metal. One of the better examples has some wit and engagement with its context – two hands, one indicating upward trends, the other gesturing a downturn, are appropriately sited in our financial district.

A third category is discernible, in which architects have worked closely with artistic collaborators to add superfluous or extra-functional parts of their buildings through embellishment and playful indulgence in tune with the spirit of the work. More formulaic approaches, exemplified by vast areas of concrete paving relieved by metallic inclusions and stencilled graphics, appear to be a growing municipal enthusiasm. My bayside suburb has just received its two percent dose, and teenage cyclists have discovered that creative tire skid marks add an extra dimension to this gift to their community. Such an uninhibited form of art criticism is a gentle reminder that not all successfully deployed art will be received without qualification. Unfortunately, in art there are no guarantees. Where risky art is avoided, the troughs may be reduced but the peaks of quality will certainly be deprived of oxygen.

Clearly there are many ways of using the two percent to deliver something interesting, uplifting and joyful. However, having been on several local government community consultation committees concerned with “environmental upgrades”, I am troubled by the prospect of large quantities of “art” appearing in our public realm that is meaningless, inaccessible and dreadfully dull. What concerns me most is the emergence of the facilitating intermediaries who act as pimps, procurers, curators, managers, commentators and shamans of this art. I suspect that the territory of public art will be captured, controlled and stifled by those who interpose themselves between makers of artefacts and those who pay for them. Are they equal to the task? Do they contribute anything worthwhile? Are they capable of imagination and understanding anything beyond what they are familiar with? Possibly not. Nearly twenty years ago I lectured at the Royal College of Art in London, where distinguished colleagues such as Eduardo Paolozzi, who did his fair share of public art, spoke with deep foreboding of a future in which art bureaucrats would become the midwives of “art”.

But sometimes they get it right. In Toowoomba, working with architect Russell Hall as “artist” on a two percent addition to a TAFE college built on the old showground, they chose a very direct approach. Eschewing obfuscation and incomprehensible private musings, they decided to make the art out of a concentrated grouping of real windmills as condensers of local memories. In the agricultural shows that once occupied the site, new windmills were often displayed, with the town itself still the proud producer of the Southern Cross that pumps water for farmers throughout Australia and overseas.

Russell chased windmills all over southern Queensland and restored the best he could find from the most unlikely piles of tangled metal parts. The austere, beautiful machines were all brought to life, re-galvanized and their painted livery meticulously rejuvenated in a metal workshop managed by his sister Jennifer. I was truly surprised at Russell’s restraint in not even tampering with the superficial graphics of these magnificent machines. Perhaps the respect came from his childhood memories of growing up on a farm, where these engines helped maintain life. On the several visits I made to his atelier, watching the project evolve was like observing a master typographer at work, arranging type sensitively, modestly and beautifully.

They could have cast something “inspired” by a windmill rotor in aluminium at several times actual size, most probably blowing the budget and dismissed by the locals. Windmills might have been the theme of some mute collection of memorabilia and marks in the paving with suggestions that past windmills were being evoked. But no! They gave Toowoomba back real memories – windmills with their working spirit, and a landmark that everyone will recognize. In addition, enthusiasm for the project brought the first national conference on windmills to Toowoomba, and resulted in an innovative design by Russell Hall for new windmill towers, an ASI award and many hours of oral history recordings, demonstrating that art can act as a catalyst across a wide spectrum when it engages intelligently. Let’s have more ART like this!

Pedro Guedes is a senior lecturer in architecture at the University of Queensland.

WINDMILLS ON SHOW, SQIT TOOWOOMBA

Architect

Project Services.

Artist

Russell Hall.

Art project managers

Martha Liew, Chetana Andary, Christine Murray, Pat Zuber.

Art advisory panel

Steve Gnatiuk, Grace Barker, Toni Reid, Sally Ogilvie, Heather Green, Deborah Tranter, Don Watson.

Oral historians

Sue Pechey, Helen Ruby.

Structural engineer

Greg O’Brien.

Construction

John Doyle, Russell Hall, Josh Hall, Jennifer Hall.

Signage

Ben Mangan (Inkahoots).