Each year since 2007, I have synthesized my ongoing research in India with my design studio teaching. One outcome of this fusion is leading third year students on study tours of the subcontinent.

Of four studio “expeditions” to date, the one made in September 2008 remains especially memorable. That year, I taught a garden design studio. In contrast to the raw “perpetual frontier” that is Perth, India’s antique garden tradition tantalized as an inspirational font. Ever under India’s spell, I conceptualized the studio’s major project as a design for the Australian High Commission’s new Chancery building at New Delhi. High Commissions or embassies and official residences of foreign ambassadors and their delegations typically feature in national capitals. Conventionally, embassies use architecture to represent national identities. I challenged my students to enlarge this approach and harness landscape architecture as an instrument of cultural signification. Along with “projecting Australia,” their designs were to respond no less sensitively to India. Students were also to address the Commission’s security requirements and the need to capture rainwater for use in the event of fire. Ideally they would produce Austral-Indian hybrids. At the studio’s outset, students investigated Australian and Indian garden typologies and constructed graphic analyses. Within days of completing these tasks, my students would find themselves jet-lagged, “culture shocked” and awestruck in the face of the Taj Mahal.

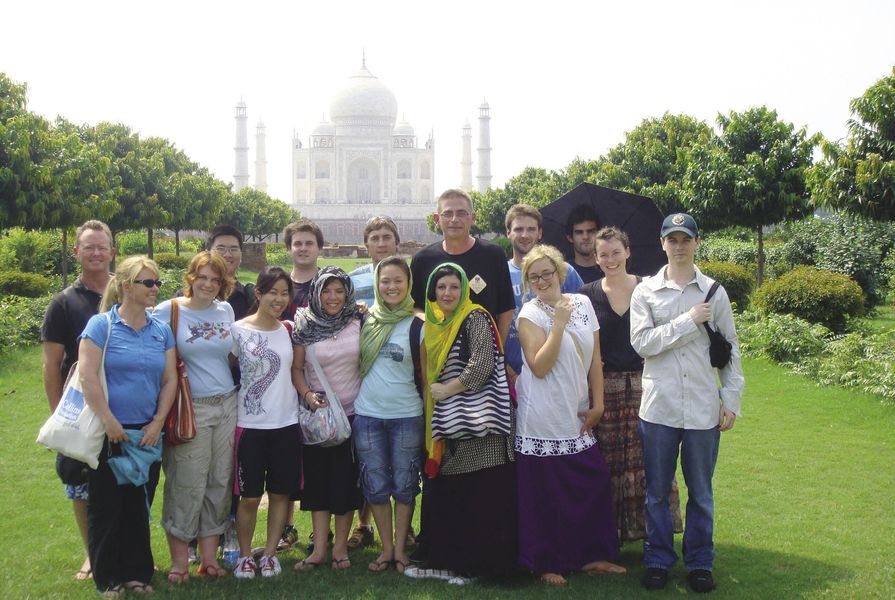

Flying into Delhi, we proceeded to Agra. The Taj Mahal never disappoints. After experiencing the conventional approach to the mausoleum, we crossed the Yamuna River to the Moonlight Garden, still under excavation. From this archaeological parkland, we appreciated the Taj’s southern front and the complex’s riverside position. We next ventured two hours overland into Agra’s rural hinterlands in search of the ruins of Mughal Emperor Babur’s Lotus Garden Palace. Discovered only in 1978 and now partly obscured by a village which grew atop it in the interim, this early-sixteenth-century garden redefined “old” for the Perth coterie. A night train to Walter Burley Griffin’s Lucknow was no less an adventure. Along with heritage sites, Lucknow provided us with a monsoon and we unexpectedly found ourselves navigating streets in waist-high water. Our cultural tourism was enriching; however, we were also “on a mission.”

Flying into Delhi, we proceeded to Agra. The Taj Mahal never disappoints. After experiencing the conventional approach to the mausoleum, we crossed the Yamuna River to the Moonlight Garden, still under excavation. From this archaeological parkland, we appreciated the Taj’s southern front and the complex’s riverside position. We next ventured two hours overland into Agra’s rural hinterlands in search of the ruins of Mughal Emperor Babur’s Lotus Garden Palace. Discovered only in 1978 and now partly obscured by a village which grew atop it in the interim, this early-sixteenth-century garden redefined “old” for the Perth coterie. A night train to Walter Burley Griffin’s Lucknow was no less an adventure. Along with heritage sites, Lucknow provided us with a monsoon and we unexpectedly found ourselves navigating streets in waist-high water. Our cultural tourism was enriching; however, we were also “on a mission.”

Returning to New Delhi, we set to work documenting our project’s site at the High Commission. We also took a serendipitous opportunity to meet and discuss our project with then Foreign Minister Stephen Smith. As we enjoyed a candlelit garden party the next night, terrorist bombs exploded nearby - emphatically redirecting our attention from India’s past to its present.

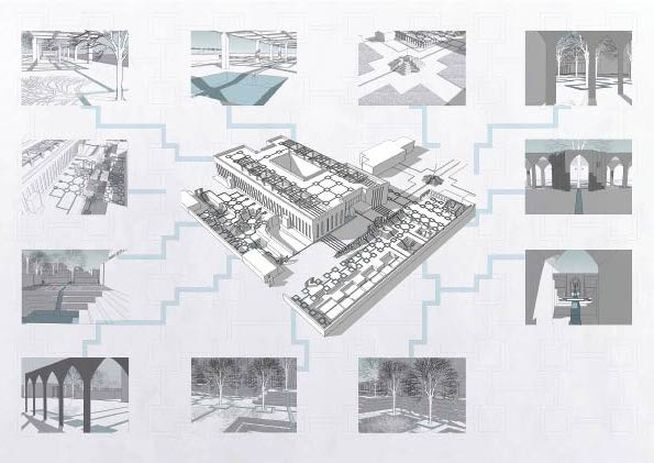

On their return to Perth, the students collated and analysed their site data and began design in earnest. By the semester’s end, each had produced excellent results. Duyen Nguyen’s design was amongst these. Nguyen’s garden takes an aqueous focus, pumping water to the Chancery’s roof. There, vine-embowered pergolas offer cool respite from the summer’s searing heat. From the roof garden, water cascades below into a concrete terrain, etched with a network of rill-linked water catchments. In the dry season, these serve as amphitheatres and sunken gardens; in the monsoon season, as pools. Corten steel archways frame a series of sequential views to and from the building. They also serve to spatially delineate the garden from the vehicle access way. Plantings of native and Australian species suitable for the Indian climate relieve the ground’s paved surface.

Early the next year, I returned to India and organized a public exhibition of the studio’s work. Held under the auspices of the Australian High Commission and New Delhi’s School of Planning and Architecture, the show was well received by landscape architects, architects and the public.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 20 Jul 2011

Words:

Christopher Vernon

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2011