REVIEW PAUL WALKER

Review

Overview of the contemplative space of the memorial, which carefully molds the site, embracing the sloping landform of Hyde Park corner to create a gentle amphitheatre.

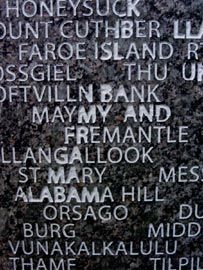

Detail of the stone panels inscribed with the names of the birthplaces of those who served and died in the Australian forces.

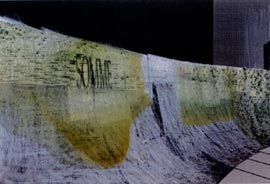

Concept drawing for the wall by Janet Laurence.

THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT is currently constructing a war memorial in London to commemorate those Australians who fought and died alongside British servicemen in the two world wars. The design of such a memorial now is particularly challenging. How can something be made to evoke memories while being inclusive; touch us emotionally without being mawkish; meet the requirements of ceremony without being pompous; satisfy the implicit expectation of monumentality while avoiding the disdain with which monuments now are often greeted? Tonkin Zulaikha Greer (TZG) and Janet Laurence’s design will achieve this remarkable trick. Simultaneously, it will mitigate the difficult conditions of its site, bringing respite to an awkward spot in London’s urban mix through its considerate design. And when it opens on Armistice Day in November this year it will have been a major logistical achievement: twelve months from selection of design to completion.

The site for the project is a prominent one at Hyde Park Corner, already a setting for a number of monuments, most notably the Wellington Arch. Hyde Park Corner is a key point on London’s great ceremonial route connecting the Admiralty Arch and the Mall, Buckingham Palace, and the Marble Arch. A privileged spot, then, with the gardens of the palace just across the road in one direction, and Apsley House (the Wellington Museum) and Hyde Park itself in the other. But the site is also, in effect, a traffic island, with vehicles swirling relentlessly around (and under) it. One condition that English Heritage set in making the site available for the memorial was that it should include a wall to shelter the site from traffic to the south. They also wanted water, and Portland stone to match that of the buildings and monuments around.

The TZG/Janet Laurence project was selected from four submitted to the Office for Australian War Graves by teams shortlisted in a competition. It met English Heritage’s requirements for the water and the wall, but opted for a greenish Australian granite instead of the Portland. The granite surfaces will bear a range of treatments according to function and their place in the design (for instance, semi-polished where there is lettering, exfoliated where the stone becomes pavement or is canted). The selected stone has both practical and symbolic rationale: on the one hand granite will cope better with water than limestone, and on the other it is a literal fragment of Australian earth given presence at the very heart of the old Empire.

A sense of land-art earthy materiality is one key to the design of this memorial. The plan form of the wall is suggested by the curvature of the outer edge of the given site. To the designers this in turn suggested the singular but irregular curves of such Australian icons as gum leaves and boomerangs. Signalled to a client body and a jury including members who might have expected such references, these ideas are happily not apparent in the final design. Rather, a more generic idea of landform is, with the plan curvature echoed by the gradual swelling in the memorial’s elevational profile, and curvature from vertical wall to horizontal pavement in section on one side (the other side – to the street – is simply vertical, an extension of the side wall of an existing subway access stair). Thus the form of the memorial appears to be a molding of the site, distinct from the object-like quality of the Wellington and the Royal Artillery monuments adjacent. The ground nearby has been contoured so that a slight bowl is suggested. The use of water, with all the redemptive qualities that it represents, is equally direct: it will flow in a programmed sequence from the top of the wall in sections along both sides of its length, modifying the visual qualities of the surface by its presence or absence and by the weathering effects it will encourage.

The memorial’s organization of form and materials might suggest a kind of natural, earthy, broad-sweeping and open Australianness in contrast to the ceremonious conventionality of old world edifices. But the detailed realization of the war memorial form adroitly negates any such essentialist reading. The curved shapes are all constructed of planar slabs of the selected stone, ingeniously fitted together, sitting on a steel frame. The artifice of the thing is overt. Construction geometry is complex: the side faces of all the slabs have to be at slightly different angles. As a consequence of the short period for developed design, consent (seventeen bodies including the Royal Household had to be consulted), and installation, time to further resolve this geometry was lacking. But there has been no problem with this practically: the slabs have been precision-cut in Australia and shipped to London, slotting into place with very fine tolerances. In some places, solid blocks of the stone obtrude from the granite pavement of the front of the memorial or from its curved base. These are seats, and stands for wreathes and military insignia.

The stone surfaces of the memorial are the ground for its other key gesture: the clever use of inscription. From a distance, in a large serif font, the randomly disposed names of battles that are the stuff of official national histories are apparent: Somme, Gallipoli, El Alamein, Singapore…. These are places in which Australia fought alongside Britain in the two world wars. Their names are clearest as they might be seen across the lawn beside the memorial to the north, for example at ANZAC day commemorations when the presence of 10,000 to 20,000 people is anticipated.

Up close, the battle names look fuzzy. They are made on an irregular ground of other place names inscribed in a sans serif font at a much smaller scale. At first glance, the names of this smaller scale are iconically Australian ones:Woolloomoolo, Narrawong, Airey’s Inlet, Brisbane. But as the gaze moves, more surprising names come up: Taupo, East London, Moose Jaw, Des Moines, Tokio. The discovery of one quirk leads to the quest for the next: a very absorbing wonder game is set up. All of these names – “Australian” or otherwise – are the birthplaces of men and women who served and died with Australian forces, as recorded by them on their service papers. They poignantly suggest particularity, the specific trajectories of families and individuals, and the location of those who died in the memories of the communities in which they were born and in which they lived. They make a mesmerising human geography. Specific history implicitly plays through the general and the official: the battle names are made out of the birth places by incisions for the letters of the latter being bolder where they coincide with the letters of the former. Some of the birth places are misspelled, some may be fictitious.

They make the ascription of nationality per se problematic – a contingency rather than an absolute – thus voiding the jingoism into which war memorials easily fall. For this reason, the presence of occasional German and Japanese places in the array is especially moving.

Cumulatively, the collection of names reflects modern Australia’s history as a nation of migrants. It will allow a visitor to see its British connections and – in all those place names derived from Indigenous Australian languages – its distinctiveness as well. Its geographical inclusiveness makes an implicit claim for tolerance. This is a remarkable proposition for a war memorial to enounce.

DR PAUL WALKER IS ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE.

Project Credits

AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL, LONDON

Architect TZG—design architect Peter Tonkin; project architect Neil Mackenzie; senior architect Heidi Pronk; junior architects Richard Healey–Finlay, Scott Davis, Etai Navon. Artist Janet Laurence. Project manager M. A.

Rafferty, Building Consultant. Structural, facade, civil engineers Arup—Andrew Johnson, Peter Hartigan, Peter Karsai, John Ryder; Arup (UK)—Bruno Miglio, Pein Lee, Darren Anderson. Water feature Waterforms International—Phil Goodwin. Electrical, lighting Barry Webb and Associates—Phil Stennett.