The story of the relationship between Melbourne architect William Lucas and the Victorian and Federal governments has a poignancy worthy of a Shakespeare drama.1 Lucas designed two major First World War memorials, neither of which was ever built: the memorial for the city of Melbourne and that located near the town of Villers-Bretonneux in France. In both cases, Lucas’s lack of success occurred under circumstances which were distressing and frustrating for him and about which he wrangled with the authorities for much of the rest of his life. And the story illustrates for us the conditions which governed the creation of Australian First World War memorials.

Fastidious and upright, he was a devout Christian and an active member of the Collins Street Baptist Church all his life. He spent 1894–1914 in South Africa, where his diverse activities included not only architecture but also missionary work and exploration. It would appear that his only major solo completed architectural works date from his sojourn in Natal.Details of Lucas’s life seem not to be recorded in any publication.2 Born in Melbourne, he served his articles in England and, in 1883, returned to Melbourne where he became a successful architect. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects (RVIA) in 1884 and a Fellow in 1888 – one of the foundation Fellows of the Institute. He became its treasurer and editor of its Journal in 1915.

His commitment to designing First World War memorials was partly due to his intense regret that Europe had wasted a generation of its youth, one of whom was his second son, Norman, who was killed in Macedonia, having enlisted just after he had completed his second university degree. Lucas poured out his anguish in a commemorative book, The Life and Letters of Norman Carey Lucas MA BSc (Edin.), Second-Lieutenant Royal Irish Rifles, which he self-published in Melbourne in 1920.

The Melbourne war memorial competition

The competition for the memorial which became known as the Shrine of Remembrance was won by Philip Hudson and James Wardrop in December 1923. Lucas’s entry was placed second, and his non-acceptance of the worth of the winning design caused him to suffer the opprobrium of his colleagues and coloured his life until his death.

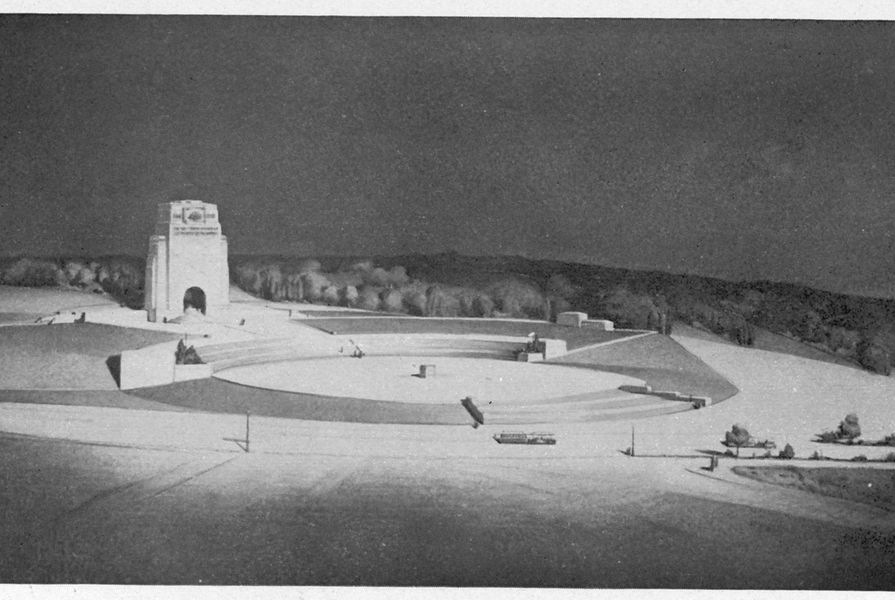

In the La Trobe Library, Melbourne, there is a carbon copy of an original typescript by Lucas dated 22 August 1924 – The National War Memorial for Victoria – a Review of the Competition. This purports to be an anonymous and objective assessment of all 75 entries in the competition but it is, in reality, a justification of Lucas’s own entry. Writing in his typically recondite and allusive prose, Lucas damns the winning design with faint praise and criticises it for its “externalism” which “invites traffic” and makes it inimical to the “holy ground concept” that he considered obligatory for a war memorial. It is “diametrically opposite” to his own “unique” design – a “vast encircling spaciousness.”

The “vast encircling spaciousness” of William Lucas’s entry in the Melbourne War Memorial competition (1923)

Image: Reproduced courtesy of the Shrine of Remembrance

Whether this remarkable document was intended as an article for the Journal of the Proceedings of the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects (JPRVIA) is not known. It was never published, but it seems that the manuscript was circulated – and Lucas was removed from the editorship of the Journal as a result. He was convicted of professional misconduct at the meeting of the council of the RVIA on 6 May 1924, and expelled from the Institute on 18 August 1924.

Although it may appear that Lucas was simply a bad loser, he seems to have been a principled and proud man who became passionately disputatious when he felt principles had not been adhered to. And his criticism of the winning design does appear to be based on principles which he himself had enunciated in 1919 in his self-published pamphlet, The War Memorial of Victoria and Capital, a Suggestion. Architecture, he says, is “the embodiment in material form of ideals” and he is optimistic that Melbourne is capable of achieving such a monument.

But Lucas’s aesthetic was too advanced for the Australia of his day. It is that of the pre-modernist architects who practised Stripped Classicism and – as such – quite incompatible with that of revivalist architecture, which was still the dominant form in Victoria up to the Second World War and which the Hudson and Wardrop design exemplifies par excellence.

The Villers-Bretonneux memorial

The town of Villers-Bretonneux, near Amiens, was the site of the battle of 8 August 1918, in which Australian divisions fought under the command of General John Monash and which was decisive in the final defeat of Germany – an event that is regularly commemorated in the towns of the district to this day.

A memorial at Villers-Bretonneux was first proposed in 1919, but it was 1925 before competitive designs were called for and 1927 before the result was announced. Entry was open only to Australians who had served in the war or the fathers of those who had enlisted (which qualified Lucas to enter). All materials were to be “durable” and Australian, and all the elements had to be prefabricated in Australia ready for erection in France. This was the major reason for the high budgeted cost of £100,000.

An interesting feature of the conditions is that the memorial should “characteristically express” the materials used – a statement that embodies the principle of integrity in the use of materials, which was first enunciated in the English Arts and Crafts movement of the late nineteenth century and which was to become a key principle of modernist design, but which had to wait some years yet before it was generally accepted in Australia. However, there is no doubt that it would have concurred with Lucas’s aesthetics.

The entire project was to be carried out “under the direction of the … Imperial War Graves Commission” and the design was to take into account the layout of the cemetery itself and the sketch design for its entrance by the “principal architect for this cemetery,” Sir Edwin Lutyens – a significant condition in the light of subsequent events.

There is no doubt that the competition judge, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, regarded Lucas’s entry as the clear winner. This would have been especially gratifying to him considering that Hudson and Wardrop’s entry was ranked only sixth.

William Lucas’s ink and watercolour drawing for his design of the Villers-Bretonneux war memorial (1930), with Lutyens’s pre-existing entrance pavilions.

Image: Courtesy Donald Richardson

However, the memorial was not built until eleven years later, and then it was not to Lucas’s design. The major cause of the postponement – and eventual cancelling – of the proposal as designed by Lucas was the serious financial condition of Australia during the Great Depression. However, Lucas did little to help the situation by his difficult attitude to certain clauses in the contract which the government was trying to negotiate with him. Also, he was reluctant to agree to a definite completion date because he believed that this would place him at the mercy of the authorities in that he would be held responsible for delays he may not have caused.

Another sticking point was Lucas’s resistance to Clause 11 of the competition, which required that visitors have free access to the top of the memorial to view the panorama of the battlefields. Lucas feared that this would allow “misuse for certain classes of mind.” In his 1919 booklet, he had stated that, in a war memorial, it would be “absolutely imperative there be no utilization of the summit of the central feature for sightseeing.” Lucas haggled with officials until the day he died, accusing them of breach of faith and unfair and unprofessional treatment. He could never have alleged breach of contract because none was ever finalized. (After his death, his executrix received the £750 which the government had been trying to get him to accept since 1932 in settlement of its acknowledged reneging on the project.)

However, the Imperial War Graves Commission continued to push for a suitable memorial and in 1935 the government asked Lutyens for a design which would cost no more than £30,000. When this became known, Australian architects generally joined with Lucas in loud opposition. In particular, the firm of Russell and Lightfoot, which had been placed second in the competition, argued that it should have been given the opportunity to re-consider its design before Lutyens had been called in. In many pages of submissions to the government it alleged that the government had “slighted returned soldiers, the architectural profession and Australians generally.” Lucas wrote numerous letters to the editors of various periodicals seeking support for his design. In August 1932, he even went to the extent of cabling the Prince of Wales, who was unveiling the Thiepval memorial to the British soldiers who had died in the Somme campaign, expressing regret that the Prince was not “on this occasion unveiling the Australian memorial,” and he informed the Australian press of his action.

Lucas followed what was the established practice of publishing an explanatory booklet on his design, forwarding copies to the governor-general and the king in 1931 – two years after the government had decided not to proceed with his design – in the faint hope that the government might re-instate the project. However, all objections from all sources fell on deaf ears.

Lucas’s Villers-Bretonneux design

Lucas’s design for the memorial – a massive tower framed by Lutyens’s gateway pavilions – was governed by the principles he had enunciated in his submission for the Melbourne Shrine, namely “something single-voiced and constant in its appeal, without over-statement,” “simple masses of masonry of cliff-like sentinel nature, in alliance with sheer majesty of scale” and “with full recognition … of the psychological tendencies to find particular meaning in the top of things and to constantly fixate the centre.” In plan, it is a square in the centre of a large, circular area of grass – a mandala in Jungian terms. However, it was never built.

Lutyens’s Villers-Bretonneux design

By mid-1935 Lutyens had prepared his first version of his design, but it proved to be impossible to build for £30,000, so cabinet voted an additional £6,000 in September 1936. This was partly necessitated by the fact that costs had risen since 1929. In particular, French workers now had a 40-hour week. The memorial was officially opened on 22 July 1938.

The Villers-Bretonneux memorial, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens. The 30.5-metre-high tower is central to three sides of a quadrangular wall with a pavilion at each end. On its top, a horizontal dial indicates the direction of London, Paris, Berlin and Canberra.

Image: Courtesy Donald Richardson

The memorial was severely damaged – though not destroyed – during the Second World War. An Imperial War Graves Commission report dated 23 April 1942, details firearms damage to the tower and pavilions, but indicates that the memorial was standing. Thus, the memorial only stood unscathed for about two years. In 1956, the Federal cabinet voted £15,000 for its restoration.

Lucas died in relative obscurity as an architect, although he had maintained his position as a prominent Victorian Baptist. An obituary in the July 1939 issue of JPRVIA made no reference to either his polemics or his architecture, but stressed his Christian values and his generosity and encouragement to younger architects. It concluded “he frequently referred to the inspiration of the Great Architect and those who knew him will agree that, in his contract with his Maker, William Lucas completed it well and has earned the spiritual reward.”

This essay is an abridged chapter from the book Creating Remembrance: The Art and Design of Australian War Memorials by Donald Richardson (Common Ground Publishing, 2014). Copies are available at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra and from the author.

1 Much of it is recorded in the massive file in the Australian War Memorial archives entitled “Lucas Versus the Commonwealth.”

2 The most complete record appears to be entries under his name in Miles Lewis’s Australian Architectural Index in the Architecture Department of Melbourne University. Also, there is a box of papers relating to Lucas in the archives of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria in Melbourne (Box 25).