Robert Grace: Tell me about your experience of the 2008 di Stasio [Venice pavilion design ideas] competition.

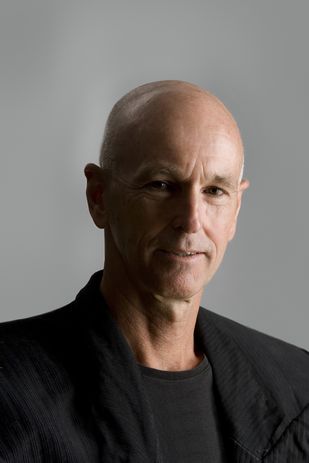

Barrie Marshall of Denton Corker Marshall.

John Denton of Denton Corker Marshall.

Denton Corker Marshall: We thought everyone is doing it, let’s not bother. Ronnie [di Stasio] rang John and asked him to enter. I was going away on holiday and the entry needed to be in in about five or six weeks’ time. I had a few days where I put together some rough old sketches and sent them in. Ronnie rang back after three weeks and said, “I love them, I love them.” It was an ideas competition, we didn’t approach it carefully – it was a throw away.

It was interesting because we had done embassies and thought about the question of trying to find an Australian expression overseas. The idea was to provide a building that said something about Australia overlaid by the gallery space.

We had done gallery spaces. We knew artists were not enamoured of overly elaborate architecture and just wanted the white space to exhibit in. We were quite happy to provide that and the black box was in contrast to it. For many years we had been toying with the idea of opening flaps up and down. We had used some fixed ones in the children’s museum. And we had this idea of simple sculptural form.

So we put those things together, the simple sculptural form and the cube with flaps opening everywhere – that was the competition entry. It was just an idea. When the actual competition came up, I realized I really didn’t know where the site was. I had never been there and I don’t think I had even seen a photo.

The area of the site was so restricted and so contained that it was almost like you take the cube form, from the di Stasio competition, and just put it on there. It was disconcerting. We considered that we had already done this and everyone in the competition knew what we had done. Should we do that again or is it not really trying hard enough?

In the end it wasn’t so simple. Reality set in. It became L-shaped in section and it had a little annexed cube, but we could fit in a perfect square plan of the gallery space. We were certainly restricted with the height and the water levels. Right through the process of the competition I was waiting for someone to ask why we were still doing the same thing. But no-one did.

RG: It seemed like the judges of the pavilion competition had your di Stasio concept in mind, where the primacy of the artist’s space was uppermost and the building was in the background.

DCM: Yes, we were quite happy with this idea and we especially believe that it is still possible to create great architecture without the screaming out, “look at me” stuff and that you can create a building that is recessive.

RG: That is very anti-Melbourne.

DCM: We are more Sean Godsell-Melbourne than ARM.

RG: I want to go back to the idea of embassies and the pavilion. How rare or unique it is for a country to represent itself on the international stage and to consider the 1988 Australia of Cox’s pavilion and the Australia of 2015.

DCM: It is a tricky situation. This is not a world’s fair. We do not want to be Gehry-esque or something overtly Australian. We thought of corten as a rusty reference to desert colours but really we are in a sort of competition with the other existing pavilion. There are some fabulous pavilions there but they are all very building-like, which is not what we were aiming for. We wanted something – I don’t really want to say a piece of abstract sculpture, but it’s reduced down, it’s not a building, it’s not a pavilion and it doesn’t have an entry (unless of course the flap is up).

Denton Corker Marshall’s deceptively simple Australian Pavilion boldly proclaims itself on the grounds of the Giardini in Venice.

Image: John Gollings

It’s almost as if it’s a sort of presence. I like to think the black and shadowy presence draws you in. For us the shadow and the trees remind us of a piece by Fiona Foley and Janet Laurence in Sydney called Edge of the Trees.1 This installation is on the site of the original Governor’s House and serves as a reminder. That when Europeans arrived and claimed the land, declaring it terra nullius, in the shadows in the trees they were being watched by the original occupants. The pavilion is enigmatic in nature in this garden and looks like it has just landed there. It’s simultaneously in your face and recessive and unassuming.

RG: So considering building in the Giardini, in a context of no context, where anything goes and there’s no restraint. Nearby you have the various neoclassical pavilions and then the main street where the pavilions line up, creating an urbanity. In the company of very important architects’ work – Carlo Scarpa, Albert Speer, James Stirling, Joseph Hoffman, Ronald and Erik Rietveld, Alvar Aalto, et cetera – this parade of embassies, how do we get an Australianness in our pavilion? In relation to Denton Corker Marshall, with your international practice and doing work all over the world? In the Giardini, divorced from a contextual situation, is it important to represent an Australian identity? Do you even see your work as Australian? Is it something you want to address or talk about?

DCM: Talking about an Australian identity, you can’t pretend people won’t see the pavilion as something that Australians think is good. We don’t think there is anything remotely Australian about it other than we are confident about what we are doing; we are not Australian in any of the superficial things, like materials. We would hope that they see Australians as being pretty gutsy for doing something like this. That’s how we want people to see Australians, as not being afraid to do it, but at the same time it’s not a “we’ll do what we want and fuck you” sort of thing.

If we had been along the street we would have had to consider it differently because we would have been part of a composition.

RG: Was it easier or more difficult not having that context?

DCM: It was easier. We were in the bush. We didn’t have to respond to the formal avenue or anything else.

RG: So it only had to respond to itself?

DCM: Exactly.

RG: Looking at Denton Corker Marshall’s work, people might say it’s not Australian, it’s architecture.

DCM: Exactly. It is architecture.

RG: Could this have been designed by Denton Corker Marshall Manchester? What does it say about DCM?

DCM: I am not sure but I know when we were working on the Stonehenge project we were not thinking that we are Australians designing in England. We are designing for the situation and its context. Each project presents different conditions that we respond to for each context.

RG: Coming full circle back to Venice where there is no context, the deliberate anonymity of the pavilion – how is that Australian?

DCM: It is and it isn’t. But what is important for us is that the building has memorability, it’s unexpected in its simplicity and its austerity, stripped and reduced, shockingly simple, and that people may not like it but they will remember the Australian pavilion. It has a further enigmatic presence: it’s a building that doesn’t exist until it opens up; otherwise, it’s just an object.

RG: The stone that clads the building comes from Zimbabwe?

DCM: Yes. We wanted to use Australian stone, a South Australian black granite. We wanted to ship over some blocks to Italy and to have them cut there. The quarry had been bought several years ago by a Chinese company, who refused our request to purchase stone. They were using it for 300-millimetre-by-300-millimetre tiles. We tried for nine months. We had to give up in the end and went for the Zimbabwe black granite.

There was quite a lot of concern initially about the use of black granite from the Heritage Authority [in Venice]; however, the senior conservation officer was very helpful, and she had permitted the Tadao Ando works at the Punta della Dogana and was very supportive of our concept. It was considered that the Giardini was not really Venice (or was an aberration) and that the black granite was authorized.

Read Robert Grace’s full review of the Australian Pavilion, first published in the July/August 2015 edition of Architecture Australia, here.

1 Edge of the Trees by Fiona Foley and Janet Laurence is an art installation commissioned for the entrance of the Museum of Sydney, which debuted at the museum’s opening in 1995. It recalls Europeans landing in Australia in 1788 and being viewed by the nation’s Indigenous inhabitants from the “edge of the trees.”