Review

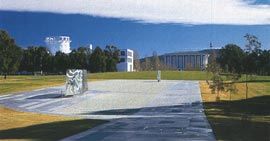

The Land Axis, with Commonwealth Place and Reconciliation Place in the foreground, and Old Parliament House and Parliament House beyond. Photograph Tim Linkins.

Lakefront view of Commonwealth Place.

Visitors gather in the cupped amphitheatre during the opening.

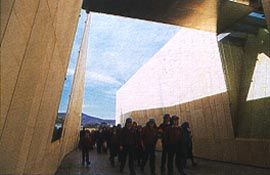

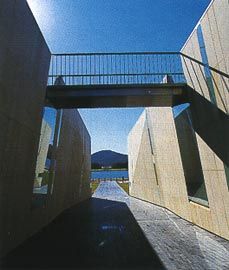

Oblique view of the space of the dividing ramp. Photographs Durbach Block.

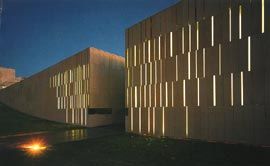

Night view of the glowing concave form of Commonwealth Place. Photograph Tim Linkins.

The divided stone wall defining the edge to the amphitheatre.

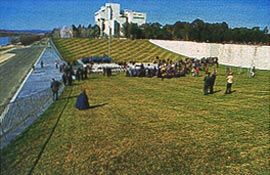

Overview showing the cupped amphitheatre with glassy spaces housed beneath. Photographs John Gollings.

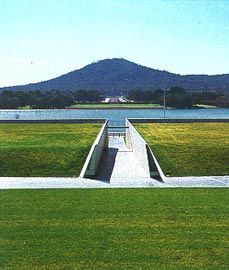

Looking down the ramp, which cuts through Commonwealth Place, along the Land Axis to Mt Ainslie. Photograph John Baker.

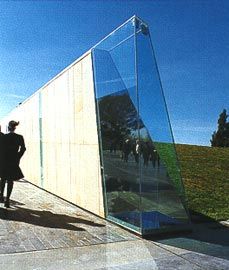

The glass and stone entry to the ramp. Photograph Durbach Block.

View towards the lake from within the ramped incision.

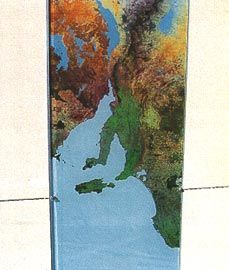

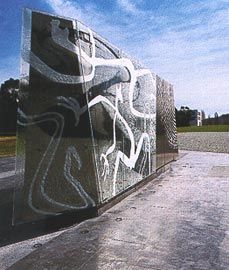

Artwork detail. Photographs John Baker.

View along the Land Axis with the mound of Reconciliation Place in the foreground and Mt Ainslie beyond. The top of this mound provides a vantage point from which both axes can be simultaneously experienced. Photograph Michael Jensen.

Looking along Reconciliation Place’s cross-axial path, which provides a seldom-experienced direct approach to the National Library of Australia. Photograph John Baker.

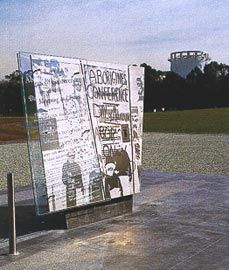

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy. Photographs Christopher Vernon.

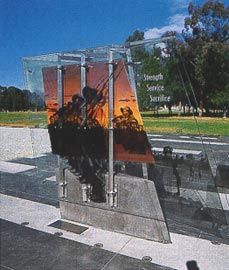

The four slivers currently in place. Photographs John Baker.

Walter Burley Griffin made what probably was his last visit to Canberra in 1934. By then, the Provisional (Old) Parliament House already was officially open and the relocation of government agencies from Melbourne was well underway. The timing of his return allowed the city’s original designer to study, as he put it, “Canberra in occupation”. From the outset of Griffin’s tenure as Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction (1913-20), the landscape architect aimed to spatially accentuate the crystalline geometry that he, along with Marion Mahony Griffin, had inscribed on the Molongolo river valley floor. Such articulation would, he believed, lend the future city a palpable sense of structural unity. In Griffin’s 1934 account, he assessed that, so far, “unity” in the protean city emanated from the emergence of his Land Axis, by then tellingly renamed “Anzac Parkway”. Griffin optimistically explained that the plan of this “open traverse axis”, was spatially delineated by the “architecture of Parliament [House] and the War Memorial” and by the “flanking plantations”, with local mounts terminating each end. His chain of “ornamental waters” had yet to appear, however, and he cautioned that the “longitudinal water axis” would “have little significance so long as the formal basins remain undermarked”. A variant of the Water Axis was belatedly inscribed through the creation of Lake Burley Griffin, inaugurated in 1964.

Today, nearly seventy years after what proved to be Griffin’s swansong reflection, the unifying presence of the Land Axis has gained a new dimension of occupation with the completion of Commonwealth and Reconciliation Places. The outcome of two separate competitions, Commonwealth and Reconciliation Places are located on the Land Axis, poised near the edge of Lake Burley Griffin. Collectively, they amplify and enhance the Griffins’’ cross-axial geometry as a source of Canberra’s unity. Since their recent dedication (and even before), however, appreciation of these projects as design propositions has been obscured by the politics of reconciliation. Controversy, however, should come as no surprise. The occupation of land is always a politicised, if not contested, activity and this site, prominently positioned on the symbolic threshold of Federal Parliament in the nation’s capital, cannot be anything but politically charged.

Nonetheless, these new design insertions also compel consideration from within other frameworks.

Commonwealth Place is the outcome of an open competition held by the National Capital Authority (NCA) in 2000, won by Durbach Block Architects in association with Sue Barnsley Design (Architecture Australia September/October 2000). Unlike those who harbour a lingering dream to “fill” the perceived “emptiness” of Canberra’s Parliamentary Triangle with a variant of Griffin’s Chicago, Durbach Block and Sue Barnsley elected to create a design which, as described by the competition jury, “cuts and forms the landscape rather than instigating a large building program”.

Commonwealth Place is, quite literally, landscape architecture.

Construction of Commonwealth Place began with an act of erasure. The site was originally configured into a cascade of earthen terraces, an embankment foundation for the lakeside Parliament House projected – along with Lake Burley Griffin itself – in British town planner Lord Holford’s post-war planning initiatives for the Commonwealth. This relic of Holford’s modernist vision has yielded to an alternative, yet no less monumental or visionary, treatment of the ground itself.

The site has been refashioned into a cup-shaped amphitheatre, evoking the dictum of Griffin’s esteemed Otto Wagner that “attention should be devoted to the monumental effect of the surface of the ground”. Surfaced with highly-manicured turf, the amphitheatre offers a place to collect and concentrate human activity. Speaker’s Square, a pavement artwork gift from Canada to commemorate the centenary of Federation, is positioned within the amphitheatre. A pool of shade is provided by a planting of silver birch trees configured in the shape of the Southern Cross – a symbolism that is perplexing in its literalness. Architectural space is folded beneath the weft of the concave form, accommodating exhibition areas, a restaurant and the offices of Reconciliation Australia. Sheathed by a facade of translucent glass, when illuminated at dusk and into the night, an ambient glow seems to radiate from deep within the earth itself. Commonwealth Place itself is divided by a ramp. This spine or incision, paved in bluestone, resonates as a sort of geological fault line or tectonic plate, metaphorically recalling the city’s underlying geological mantle that is visible nearby in the roadside cutting of State Circle, further up the axis. Through its provocative engagement with the ground itself, Commonwealth Place is one of the first designs to treat the Land Axis as more than merely a surface framed by a surrogate architecture of trees.

Reconciliation Place is the result of another NCA competition, won by a team led by architect Simon Kringas in 2001 (Architecture Australia September/October 2001).

Until the construction of Reconciliation Place, Indigenous presence in the Parliamentary Triangle was, at least overtly, concentrated at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy complex prominently located at the steps of the now long-permanent “Provisional” (Old) Parliament House. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy and its dynamic, expanding surrounds is surely one of the most symbolically charged landscape spaces on the Land Axis. Here, the landscape itself is employed as a medium of protest.

Emanating from the embassy structure is an array of outlying gunyahs, a perpetual fire and clandestine plantings of eucalypts – errants or escapees from the confining geometry of the plantations flanking the axial corridor. Even the space within the plantations has been colonised as a locus of habitation and literal occupation. The controversial decision to locate Reconciliation Place at some distance from the longestablished Aboriginal Tent Embassy led some to speculate that the aim of the new project actually was to relocate Indigenous presence to a less confrontational position and to eliminate the embassy itself.

Unlike the use of landscape at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, at Reconciliation Place the site is given a more benign role as a receptive surface. Reconciliation Place is a cross-axial pedestrian way connecting the National Library of Australia (NLA) with the National Gallery of Australia (NGA). A composition of sculptural “slivers” of varying heights, each representing in word and image episodes in the reconciliation process, is positioned within this corridor. There are multiple possible routes through this grove of slivers, each offering a different reading. The distribution and concentration of the slivers, however, is not random. At strategic points the slivers are positioned in response to views of nearby buildings. Perhaps most remarkably, Reconciliation Place provides a seldom-experienced direct approach to the NLA.

Like its vegetal counterparts, the sliver grove is to be dynamic. The promenade and slivers are already in-place as a skeletal framework, and it is intended that the ongoing unfolding of “reconciliation” will be marked by the accretion of new slivers of varying heights. At the moment, however, this grove seems rather sparse. In the future, as the visitor weaves through Reconciliation Place from either the NGA or NLA, the (hopefully) increased number and density of slivers will dramatically punctuate the sense of lateral spread upon arrival at the promenade’s open centre. Here, the cross- axial intersection between Commonwealth and Reconciliation Places is marked by a dome of turf. Functioning as a viewing platform, this convex earthwork was inspired by the Aboriginal middens and the mounds produced by wind action that Kringas encountered on treks to the plains of western New South Wales. In this environment, not unlike the level circumstance of Griffin’s own American prairies, even the subtlest of elevations become lodestones for human congregation, providing welcome opportunity for prospect of the wider landscape. The dome is notched in two places; the first is occupied by a bench for contemplation with attendant plantings of indigenous vegetation, and the second provides a speaker’s podium. Although unintended, the construction of this new landform might also be read as a sort of spoils, evocative of the original hills and spurs levelled in Canberra’s development. As early as the 1920s (if not before), however, the city’s maker’s were confronted by the reality that antiquity on the limestone plains was not limited to the geological.

Excavations made in the construction of (Old) Parliament House not only altered topography but also unearthed Aboriginal artefacts.

The 1934 Canberra Annual reported that “the exigencies of war and the compromises of peace” conspired against the national capital’s timely construction.

Decades later, the “compromises of peace” resulted in what is, at best, a tenuous relationship between the adjoining Commonwealth and Reconciliation Places. As originally envisaged, the ramp bisecting Commonwealth Place was to be far longer, rising more gently to meet grade. This element was dramatically truncated as a result of the NCA’s efforts to accommodate the transgression of Reconciliation Place into the boundaries of Commonwealth Place. Construction of Commonwealth Place’s ramp to the original design would have enabled one to see down its length to the lake from Old Parliament House, visually reassembling and linking the Land and Water axes. Instead, this view is now blocked by Reconciliation Place’s turf dome. A fragment of this water view, however, is recaptured (if not appropriated) from atop the midden. This vantage point is a nexus from which both axes can be simultaneously – and almost ethereally – experienced. Most disappointingly, however, the view up the Commonwealth Place ramp from the lake’s edge is foreshortened and terminated by the midden, its arcing profile outlined by the iconic flagpole of Aldo Giurgola’s magisterial Parliament House.

Coincidentally, the earthen terraces previously on site were similarly framed when viewed from this spot. Ultimately, however, a disturbing sense of disjuncture, if not collision, pervades the interstices of the two compositions.

Commonwealth and Reconciliation Places, as with virtually any development proposition in Canberra, inevitably will be measured against often divergent interpretations of the symbolic, if not structural, content of the “Griffin Plan”. Given this, it would be wise to more comprehensively identify and consider Griffin’s own dynamic views of the city’s organic design. One aspect of the contemporary mythology surrounding Griffin and his association with the national capital suggests that after the 1921 abolition of his official position, Griffin viewed the work of his committee of successors with monolithic contempt. When interviewed by the Canberra Times in 1926, however, Griffin actually gave the “impression of an artist, who takes a true artist’s pride in the work which is being carried out [at Canberra] even if it is not, in every detail, in accordance with his own ideas”. Even in its modified execution, Commonwealth Place offers an object-lesson as an at once a respectful and poetic interpretation of the spatial implications and possibilities of the ever potent “Griffin Plan”. Reconciliation Place is no less compatible. Both are design achievements of which the nation can be proud.

Christopher Vernon is senior lecturer in landscape architecture in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia

Project Credits

Commonwealth Place

Architect Durbach Block Architects in association with Sue Barnsley Design—project team Neil Durbach, Camilla Block, David Jaggers, Joseph Grech, Lisa Le Van (Durbach Block); Sue Barnsley, Josephine Williams, Katherine Hipwell (Sue Barnsley Design). Lighting Design J3 Design— Jerry Retford. Facade Design Hyder—David West.

Project Manager Weathered Howe. Builder Manteena. Client and Development Authority National Capital Authority—Annabelle Pegrum Graham Scott-Bohanna, Andrew Metcalf, Craig Egle, Robert Tindal.

Project Credits

Reconciliation Place

Stage 1%br% Architect Kringas Architects—Simon Kringas; Indigenous team member Sharon Payne; other team members Agi Calka, Amy Leenders, Cath Elliott, Alan Vogt. Indigenous Cultural Advisor Sharon Payne. Civil Engineer Young Consulting Engineers. Structural Engineer Advanced Structural Designs. Electrical Engineer Webb Australia.

Exhibition/Graphic Design Benita Tunks, Marcus Bree, Alan Vogt.

%br%Stage 2%br% Architect Kringas Architects. Indigenous Reference Group Sharon Payne, Agnes Shea, Margo Neal. Exhibition Designers Liquid Design Delivery Team. Graphic Designer Alan Vogt.

Aboriginal Cultural Advisor Sharon Payne.

Managing Contractor John Hindmarsh. Quantity Surveyors Donald Cant Watts Corke. Sliver Fabrication Border Stainless Steel. Image Permission, Slivers National Library of Australia, Glenda Humes, Colin and Paul Tatz, Jamie Squire, Patty Walker, Australian War Memorial, Marcus Bree, GEOIMAGE, Marianne Walsh, Jimmy Williams, Brendan Tunks, Lorna Lippmann, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Merle Jackomos, Faith Bandler, Canberra Times, Debbie Rose. Richard Woldendorp, Karen Casey, Trevor Graham, Haddon Collection. Audio Rick Rue.