Barangaroo Reserve, at the northern end of the Barangaroo precinct, has transformed the one-kilometre hardstand apron that was once part of Sydney’s industrial harbour into a new, though artificial, headland. US-based Peter Walker and Partners Landscape Architecture (PWP), in association with Sydney-based Johnson Pilton Walker Architects and Landscape Architects, brought this design exercise together and helped to resolve some of the vastly convergent issues that Barangaroo inspired – both politically and in planning and design terms.

In 2005, the state government launched the East Darling Harbour International Urban Design Competition for the transformation of the Barangaroo precinct. The winner, announced in 2006, was a team comprised of Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects, Paul Berkemeier Architect and Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture. The proposal interpreted the site “as a series of urban projects that reunite the city with its harbour, including a collection of strategic urban linkages and the creation of a new finely calibrated and adaptable urban grain. The proposal enshrines the western foreshore as an inalienable public place belonging to the citizens of Sydney.” Congratulating Jane Irwin at the time for her part in the winning team, I acknowledged the thrill it must have been to be so identified.

Soon after, the concept of a “headland park” was conceived and later adopted, leading to a great disappointment for the then-winning team. It was promoted by former prime minister Paul Keating, who pursued (somewhat determinedly) the new concept of a headland parkland in the middle of Sydney Harbour. A headland park was included in the scheme by Richard Rogers Partnership, Lippmann Associates, Martha Schwartz Partners and Lend Lease Developments, which was highly commended in the 2005 competition. Keating’s vision was to return the area, then known as Millers Point, to “a naturalistic park,” which would complement the other four headlands in the western harbour: Balls Head, Ballast Point, Balmain and Blues Point.

In 2009, for the second stage of design submissions for Barangaroo Reserve, I joined with Hassell (which had been very successful in its earlier involvement in the production of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games). Our team was recognized as a finalist, with the Johnson Pilton Walker/PWP team successful. I have had a long-term interest in the gradual evolution of an Australian indigenous design environment for the Sydney Harbour context and for landscape development in Australia. The headland concept was an exciting prospect. While we were unsuccessful in our Barangaroo bid, I am able, some years later, to provide comment on Barangaroo Reserve, which is now open to the community.

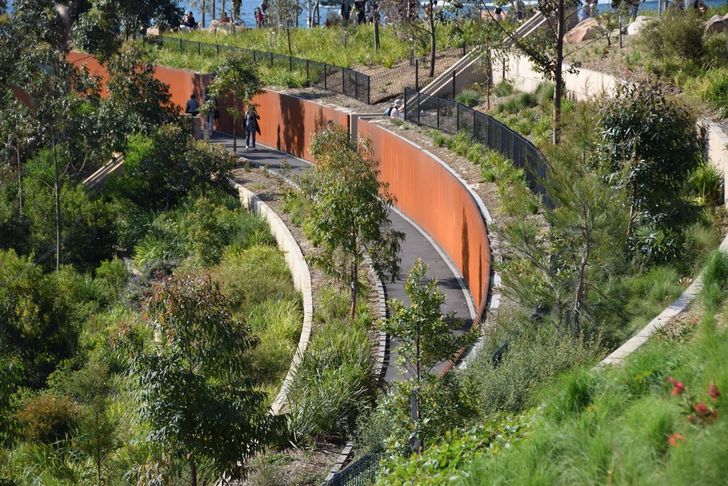

New ‘old’ native planting.

Image: Bruce Mackenzie

A naturalized parkland

Creating a “naturalized parkland,” per se, is not possible. There are physical, mechanical and reasoning matters that forbid such an endeavour. There is no way to conjure a headland of rocks (huge rocks) and cliff faces, with cascading but tightly bound soil in an intense concentration of forms meant to represent a new geomorphology in an urban sense. The nearest we may get is a standard rockery, a large one, which would be in effect ludicrous. However, design inspired by nature is a genuine prospect and can be achieved with style, whether at Barangaroo, Sydney’s Martin Place, Melbourne’s Swanston Street or anywhere.

Indigenous planting

Many factors can enhance the sense of a space being inspired by nature, one being the vegetation. At Barangaroo, the vegetation is a fairly genuine representation of the genera, species and forms of the local endemic Hawkesbury sandstone landscape defined by Stuart Pittendrigh, an experienced landscape architect and a talented plantsman. His work, always proficient and knowledgeable, was studied and researched to arrive at a true reflection of nature in these new circumstances. There are over 76,000 plants at Barangaroo Reserve, including 923 native trees, palms and tree ferns, 1,935 native shrubs, small trees and Macrozamias, and 73,200 native groundcover plants, vines, grasses and ferns. I note that five of the eighty-four species are not native to the headland location, instead chosen because they are seen to be iconic plants of the Sydney basin. This is a pity and while I don’t apply such rules to gardens generally, especially home gardens, the garden at Barangaroo Reserve can be unique and could only be enhanced by a plants regime that is genuinely authentic.

At the time of writing, in spite of the semi-mature and larger transplanted specimens installed, the planting is (of course) still immature, presenting a day-one effect in great style, waiting for future years of progress. The growth in just the next five to ten years will be spectacular and in forty to fifty years’ time (also given that natural seeding should occur) will look as if it has been there forever. The growth, in typical native plants’ style, will be wild, random and intertwined in character and harmony. The result will be a confusion of plants, textures, scents and sounds enhancing the walls and terraces that will to some extent belie the basic formality of the park’s layout. Species were chosen from the ridgetop woodland, heath and scrub, open dry forest, tall moist forest, damp gully forest and headland waterfront environments.

The site has been terraced evenly, following the shape of the main pedestrian promenade.

Image: Bruce Mackenzie

The soil scientist

The work of Simon Leake, a dedicated soil specialist, can be added to this plants story. He came to the Barangaroo project with experience of the 2000 Sydney Olympics site, where he initiated the on-site development of soils from crushed sandstone and other relatively innocuous derivatives. At the polluted Olympics site he had to install some six hundred millimetres of “artificial” soils over a bland consolidated clay base not very different from that of a concrete platform. This soil was given a title, “facsimile soils.” Over it was planted an indigenous cover of five hundred hectares of plants endemic to Homebush Bay, which have since thrived.

At Barangaroo many years later, Leake extended his theories on the requirements of sandstone native plants and in doing so had this special experience: “I was sitting at Somersby, on the Central Coast [of New South Wales], and a bushfire crew passed by and said they were just going to put in a controlled burn. So we rushed out and got some soil samples before the burn, and then went back again once the fire had gone through.” The before and after samples showed that phosphorus levels rose from 46 ppm before the fire to 90 ppm afterwards. Similarly, calcium levels rose from 336 ppm before the fire to 756 ppm afterwards. It is important to know that phosphorus levels and nutrients generally in this native plants regime are limited and relatively precious in relation to the success of plants’ survival. As it was revealed, the nutrients were held to some extent in the body and foliage of the plants and released to the soil after the fire passed through. In “normal” soil the phosphorus levels can, for example, go from 300 ppm to as high as 1000 ppm. Now it became a question of working out how much green waste compost should be added to the soil mix to mimic the effect of a bushfire. No fertilizers were used at Barangaroo Reserve initially. This is startling stuff, an improvised facsimile soil component from waste materials that supports a rich cover of valuable native plants.

Plant material was pre-grown at the nursery in manufactured soils similar to those that were created on site. Crushed sandstone was the major raw material at Barangaroo Reserve, being extracted from Barangaroo South and used to fill the new headland formation. It is important to note that 99 percent of the plants on the site have taken successfully and the growth rate has been remarkable.

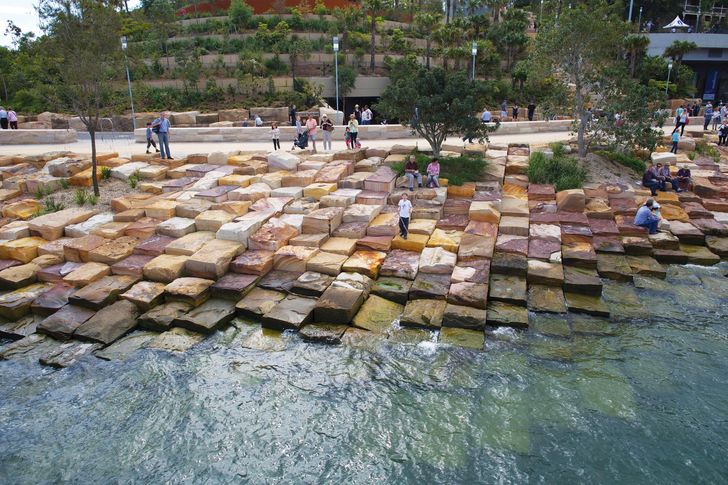

The foreshores of the reserve have been formed in a style that represents the natural formation known on the coast as “tessellated pavement.”

Image: Courtesy Barangaroo Delivery Authority

A tessellated pavement

The foreshores of the reserve have been formed in a style that represents the natural formation known on the coast as “tessellated pavement.” The most common type of tessellated pavement consists of relatively flat rock surfaces, typically the tops of beds of sandstone and other sedimentary rocks, which are subdivided into either regular rectangles or blocks approaching rectangles by well-developed systematic orthogonal joint systems. The surfaces of individual beds, as exposed by erosion, are typically divided into squares, rectangles or, less commonly, triangles. Johnson Pilton Walker came up with the idea of using the north-east to south-west sandstone bedding, with the weathering patterns found on Sydney’s exposed sandstone escarpments, to structure the design.

The sawn rocks of quite large proportions used in this process have been extracted from within the site in the process of making spaces, underground, for a carpark of three hundred places and the intended cultural centre. The underground space overall constitutes a vast chamber waiting on further design development and associated funding to make it happen. The placement of these rock elements on the foreshore makes an important configuration, reflecting the patterns of a natural tessellated pavement system in a stylized way. Some thousands of blocks have been extracted and installed to create the sandstone foreshore, complete with tidal pools, escape zones for shelter and small picnic areas, including shaded areas, for relaxation. The patterning arrangement is made to emulate the essence of the formation in nature. This is an inspired development that imagines all sorts of possibilities and it adds enormously to the overall quality of the park’s design.

Configuration and construction materials

Construction materials and configuration go hand in hand, reflecting the structure of the park’s layout, which is conscientiously formal in nature. The designer’s hand is very evident and the site has been terraced evenly, following the shape of the main pedestrian promenade, which in turn is parallel with the layout of the bitumen-paved roadway, curving consistently within the site’s seemingly randomly arranged edges. The materials comprise bitumen, bitumen with bluestone margins, a hard gravel pavement plus bluestone edging, sawn stone as balustrade walls, sawn stone as steps, low sawn stone wall dividers, cut rock edge details on paths, concrete terrace walling, Corten steel terrace facing, concrete wall structures and concrete edging. Grass is an important part of this mix, coaxing large and small groups to use the space according to their needs – eating, collaborating, listening to music, running, relaxing and at times exploring, just walking or cycling for the sake of it. The formal layout reduces the intent to create a “natural” response to the site and the main stair flight is a bit daunting, centrally located and without any attempt to diminish its presence. Aside from the stair’s obvious purpose, it is also a spectacular assemblage of steps, rocks and vegetation, making a colourful display. The symmetry of the promenade running parallel to the roadway comes at the expense of the “naturalness” that could have been desired for the headland park. The people using the walkways walk and sometimes run, but never in a manner that requires a smooth curvilinear layout. These are design decisions deliberately made to demonstrate formality at the expense of simplicity. However, users have little awareness of these design deliberations and can be seen to be warmly engaged in the park’s offerings.

The placement of the large sawn blocks of stone that line the path edges and roadways is a good move – it extends the implied patterning of the tessellated pavement used at the headland edges and repeats the block size and bulk throughout the park in detailed applications. In time, of course, the bright gold and red hues of the stone blocks will recede as weathering effects take over. The initial character is at present attractive but the eventual weathered grey will be totally appropriate.

Barangaroo Reserve is visually connected to landmarks including Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Image: Bruce Mackenzie

Views to and from the park

Views from the park are simply spectacular. They encompass the urban skyline, the harbour and the extensive development along the harbour shorelines, including the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and an endless array of boats. People, young and old, are seen in a mix with rich vegetation against the background of a stylish city skyline. These abundant views are a delight for the park’s visitors and it is interesting to note that since the 1970s, when a move was made to introduce harbour-side native planting to new parks (Illoura Reserve at Balmain was a start), landscape architects have established a whole series of harbour-side parks at places such as Yurulbin Park, Sawmillers Reserve, Mort Bay, BP Waverton, Pirrama Park and Ballast Point.

From viewpoints off site, Barangaroo Reserve makes a startling impact, set within a colourful panorama of city skyline, harbour bridge, other headlands and parklands and, again, the harbour alive with boats. The number of visitors using the park is substantial. This is increased to some extent by its newness and its current publicity, but current visitors will be replaced later with people who learn of its delights and go there for that reason alone. Many people will also use this park when they visit the yet-to-be developed cultural centre.

To summarize

It is difficult to address Barangaroo and not get caught up in the endless disparagement applied to the whole scheme. While I am not too distressed by these implications, I am left with a great admiration for Barangaroo generally and for Barangaroo Reserve, put together with the skilled and earnest work of many designers, especially Peter Walker and Partners Landscape Architecture and Johnson Pilton Walker. Barangaroo Reserve is, of course, funded by the product of Barangaroo, the urban development that made it all happen.

While I am perhaps not overwhelmed by every detail, I am overjoyed with the result. This is a successful project and represents a grand contribution to a contemporary Sydney setting.

Credits

- Project

- Barangaroo Reserve

- Landscape architect

- Peter Walker and Partners (PWP)

- Landscape architect

- Johnson Pilton Walker

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Consultants

-

Architect

WMK Architecture

Civil and structural engineer Robert Bird Group

Construction manager Evans and Peck

Construction observation Tract Consultants

General contractor Lendlease

Geotechnical engineer Douglas Partners

Historic interpretation Judith Rintoul

History and arts Peter Emmett

Horticultural consultant Stuart Pittendrigh

Hydraulic engineer Warren Smith Consulting Engineers

Landscape contractor Regal Innovations

Lighting engineer Webb Australia Group

Marine engineer Hyder Consulting

Plant supply Andreasens Green

Quarry operation and chief stonemason Troy Stratti

Sandstone adviser Ron Powell

Signage and wayfinding Emery Studio

Soil science SESL Australia

Traffic engineers Halcrow MWT

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

Type Adaptive re-use, Outdoor / gardens, Parks, Public / civic

Source

Project

Published online: 29 Jun 2016

Words:

Bruce Mackenzie

Images:

Bruce Mackenzie ,

Courtesy Barangaroo Delivery Authority,

Courtesy PWP Landscape Architecture

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2016