Looking west along the south facade, with the entry in the distance. Image: John Halfide

The quiet room at the building’s eastern end. Image: Sharrin Rees.

The ground level spa. Image: John Halfide

Parents accommodation. Image: John Halfide

Interior of the multi-sensory room. Image: John Halfide

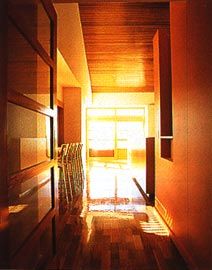

Looking along the main east-west corridor on the first floor. Image: Sharrin Rees.

MSJ’s Bear Cottage is the first dedicated children’s hospice and respite care facility in New South Wales, a service provided by Westmead Children’s Hospital. The novel concept of a children’s hospice suggests the need for a domestic setting, but with all the functions normally provided in an institutional environment. The meeting of these two radically different types of setting in Bear Cottage raises important questions about how architecture, and the inhabitants, negotiate this hybrid condition.

Sited on the grounds of the historic St Patrick’s Estate in Manly, Bear Cottage enjoys a privileged location, both in terms of its seaside surrounds, and its position in the established grounds of St Patrick’s. The building responds to this site in a variety of ways. On entering from the south-west corner, the established grounds open up to view as a pathway meanders to the building’s entrance, which is on grade at the second and principal level of the building. The south-eastern edge of the building steps away towards the north, following the line of an existing ridge in the site, reducing the visible mass of the building. The entrance scale is immediately that of the domestic. The separation of pitched roofs (required by the existing heritage context), two apparent chimney elements (concealing ventilation and lift machinery), screened outdoor spaces and a small water garden further suggest a domestic condition.

The principal level of the building is organised along an east-west corridor, and efforts have been made in the planning of the major spaces to suppress an overtly institutional feel. The corridor widens at particular points to create a north-lit sunroom and a wider movement bay adjacent to the lift (discreetly turned away from opening directly onto the corridor), and the kitchen/dining room. Communal spaces, residents’ bedrooms, and administration and care facilities are all organised at this level, with more intensive palliative care offered in suites of rooms at a discreet distance from communal areas. The level below contains other recreational facilities on the northern edge, including substantial outdoor space, two two-bedroom self-contained apartments to enable parents and families of children to stay on site, and to the south, service spaces and enclosed car parking.

In the upper-level interior spaces, a warm colour palette replaces the grey-neutrals of traditional institutional surfaces. Corridor wainscoting and handrails, normally required by regulation in health facility buildings, are not present, and what emerges in their place are careful demarcations at the points of transition between public and private areas. Thresholds between bedrooms and the main corridor are marked with parquetry zones between standard carpet colourings. The bedrooms themselves suggest a kind of hotel/domestic hybrid. The provision of private outdoor space and personally adjustable environmental controls does much to de-institutionalise these spaces, along with the concealment of medical gas outlets within the lines of a recessed shelf above each bed.

In all of these ways, architects Mark Willet and Katherine Lakis have attempted to enact the domestic in this institutional context, and to achieve this, they were forced on occasion to argue against certain requirements in the class 9a regulations. It was clear from my visit to the building that its sense of the domestic had been taken further, by both staff and children alike, in the ways in which the spaces had been inhabited. Like all successful domestic inhabitation, the placement and movement of objects and furnishings tends to push to the background and in some senses transform the careful spatial articulation which is the job of architects. Bear Cottage is full of stuffed teddy bears which find their own home seemingly on any available surface. The inhabitants of Bear Cottage have taken up, unknowingly, but in a witty and unselfconscious way, the nineteenth century notion of furnishing as upholstery, the provision of soft “stuff” to cover the hard edge of architectural space.

And here, questions are raised about this meeting of domestic and institutional space, not in terms of how successful Bear Cottage is as a health facility, but rather in terms of how this condition needs to be represented, in architectural terms, as domestic. I am still equivocating over whether Bear Cottage requires a domestic setting, or creates it through architectural intent. I suspect it is a combination of both. On the one hand there is the client’s quite reasonable desire that this building be deliberately noninstitutional (and it seems that the domestic is the default opposite of the institutional), and, on the other, the heritage context equates the domestic with the unobtrusive and the ideologically neutral (notwithstanding that the encroaching housing development to the site’s west would appear to break both of these assumptions, in being both obtrusive and enclave-like).

It seems pedantic, but I want to draw a distinction between the domestic as a form of inhabitation, and the appearance of the domestic in architectural form. The former is the province of the inhabitants, be they health worker, child, or child’s parents. The latter is the province of architecture’s reception in a variety of public and professional contexts. The architectural condition of Bear Cottage clearly represents domesticity. Published here, without its bears, it offers a kind of professional reassurance that architectural technique alone can smooth the seams between the domestic and the institutional. However Bear Cottage is not just another sort of house. The truest test of a building such as this is the way in which it invites inhabitation; the way in which it invites a literal remaking of its spaces, so that each inhabitant of Bear Cottage can make it into their space, whatever that space may need to be, for the duration of their time there.

The architects have had to negotiate the process of the building within the difficult context of competing demands. During my visit with Mark Willet and Katherine Lakis, I sensed that they enjoyed, but in some instances were a bit dismayed by, seeing some of the ways in which the building has been inhabited. This is exactly as it should be. The line between architectural design and inhabitation, just like the line between the domestic and the institutional, is a tricky one for all parties to negotiate.

Credits

- Project

- Bear Cottage, Manly

- Architect

-

McConnel Smith & Johnson

- Consultants

-

BCA consultant

Trevor Howse & Associates

Builder Multiplex

Hydraulic engineer Ove Arup & Partners

Landscape architect Site Image

Mechanical and electrical engineers Ove Arup & Partners

Project manager DPWS

Quantity surveyor Page Kirkland Partnership

Structural and civil engineer Ove Arup & Partners

- Site Details

-

Location

Manly,

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Health