Oblique view along the lower level of the Australian Pavilion. When is spelt out along the back wall using cubic volumes that allow the letters to be coalesce when seen from particular angles. Photography John Gollings

The Australian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale is now open. Carey Lyon and Rachel Hurst reflect on the Now + When exhibition, whole Mirjana Lozanovska comments on the Biennale as a whole.

MEDIUM AND MESSAGE

Looking at the Now section of the exhibition on the upper level, with the entrance seen beyond.

Aerial view of the mine at Kalgoorlie. One of the mine-scapes presented in the When section of the exhibition.

Aerial view of Melbourne, one of the series of city-scapes.

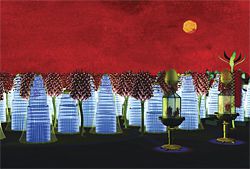

Edmond and Corrigan’s City of Hope, from the When section.

CAREY LYON

It is difficult to separate a review of Now + When from the expectations built up through advanced publicity – part necessary promotional strategies and part rather excessive boosterism. Much of this advanced press focused on the new technologies being trialled (complete with action photos of one of the creative directors leaning out of a helicopter) and the promise, quite literally, of a spectacle. Conversely, the sixteen exhibitors within the When component of the exhibition hovered somewhat below the promotional radar, inviting curiosity about the exhibition’s content. The promise of a spectacle seemed to be offered as a calculated polemical position by the creative directors in relation to the two previous Australian Pavilion exhibitions in 2006 and 2008, which were summarized as “academic” and “boring” in various dispatches and interviews. This is not to suggest that the 2010 show was primarily constructed as an opposite – “accessible” and “spectacular” – however, it did convey an interest in the relationship between architecture and new media; if not an idea about the blockbuster, then at least a serious interest in the box office receipts.

All of which, for your reviewer, made for both curiosity, scepticism and trepidation in entering the blackened pavilion on a hot and humid Venice morning. It has to be said that from the first disorienting blackened interior, with a physically immersive soundscape (by Nick Murray and Carl Anderson), the concept of the spectacle succeeds in all the ways intended. Weary biennale visitors on the national pavilions trail within the Giardini can have an immediate media fix in the space of a ten- or fifteen-minute stay, as a passive participant if they choose. Stand still with 3D glasses attached and the content comes to and indeed at you. Unexpectedly, this structured passivity of the visitor creates a meditative quality for the Now part of the experience. It invites you to participate in the spectacle as a kind of media event and also to step into its stereoscopic world.

So what is it that we see? The actual technical achievements of the stereoscopic images are difficult to evaluate, but as we are all now dedicated and relatively sophisticated consumers of new media, its immediate and explicit novelty passes quickly. Nevertheless, the Now images are extraordinary to stand in front of and, in fact, to see inside of, due to the technology itself. The images taken at dusk of Sydney, Melbourne and the Gold Coast are brought alive by the stereoscopic process – pulsing and teeming, simultaneously intensely beautiful as a human enterprise and shocking as the visceral intensity of the energy burn jumps out of the screen toward you. The parallel images of the open-cut mines from remote Western Australia also have a terrible beauty in the scarified landscapes, yawning scars for the doubting Thomases of environmental havoc. Carved out by access roads, these mine images have an almost mythical, even biblical, quality – like ruins of a lost civilization, or a wizened Tower of Babel as a harbinger of catastrophe.

The juxtaposition of the city-scapes with the mine-scapes is not subtle (it certainly isn’t “academic”) but it is powerful and creates an interesting disruption in one’s mind. Like a well-made thirty-second ad it gets its message across (cuts through, to use media jargon) – lest we forget where our cities come from, like the slaughterhouse to the supermarket shelf. Within the Australian context it takes that to which we are culturally blind, the “other” of our interior, and transposes it dramatically as a paired equal to our everyday fringe-dwelling existence. This artificially constructed mutuality can be held clearly in our minds and eyes through the joining of the message with the media.

It also invites us to contemplate whether there is still some resonance in the Marshall McLuhan paradigm that the media is the message. This may be a subtext to the creative directors’ primary interests and it seems to propose that the technique itself (stereoscopic imagery) might offer architects and urbanists a new way of both seeing and representing. With earlier representational tools such as plans and sections now heading for redundancy, and parametric modelling lurching towards ubiquity, you get the feeling, standing with your 3D glasses on in the pavilion, that you are looking into another paradigm shift in technique. Embryonic and uncertain as this technique may be, it is a window into another way of seeing – and another way of seeing must eventually allow us to find another way to think about architecture and the city.

Whereas the Now images have the certainty of the existing world to provide a stable locus from which the new media can be contemplated, for the When component it becomes something else entirely – far more cinematic and unfamiliar. The creative directors have discussed the sixteen contributions by the various teams as something more than a direct speculation on the future of the city through environmental, geopolitical and population change, claiming a wider allegorical quality for the propositions. The resulting contributions require us to suspend disbelief, in the plausibility of each idea, and to participate in them as almost filmic imaginings of future worlds.

On the first run-through of the pavilion’s twelve-minute video loop of the sixteen propositions, the allegories are, for the most part, pretty grim and foreboding. There is not a lot of optimism about these future dreams and quite a few nightmares – an effect compounded by joining each of the sixteen worlds together as a continuous loop, without a break or even a “reboot” as we enter each new and distinctively authored world. Some of this may have been overcome by the creative directors exerting a stronger critical selection of the presentations, culling out enough to provide those with greater depth (intellectual as opposed to stereoscopic) more space to open up their worlds to us. Even in a practical sense, sixteen exhibitors over a twelve-minute loop is not a lot of time in the sun for what looked like a hell of a lot of work by each contributor.

A number of exhibitors took the creative directors’ brief rather literally, generating straightforward, reactive strategies to the prospect of massive change, particularly to the consequences of rising sea levels. Many of these imagined worlds offer little more than future cities of so many data-scapes (tower equals population density), or simply maintain the professional niceties of the urban planning discipline in spite of what would be, in the scenario of the biblical flood, surely more visceral and more physically catastrophic – like Lake Pedder or the 2005 tsunami. Even with the best efforts by exhibition animators (Flood Slicer), a number of these schemes come across as anodyne.

Within this genre, however, a couple of schemes stand out as notable exceptions, primarily by conveying a sense of the city’s capacity for adaption rather than reaction. Saturation City (by McGauran Giannini Soon, Bild + Dyksors and Material Thinking) heightens the sense of catastrophe by connecting it to familiar yet radically altered typologies – positioning Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance in a strange sunken island and generating immense floating megastructures made out of piled up suburban houses, at once ordinary and shockingly dislocated. Symbiotic City (by Steve Whitford and James Brearley) similarly expands the idea of adaption, with the City of Hobart reinventing itself around the urban detritus of catastrophe, and with a curious overlay of the Asian metropolis, as though, in a dramatic realignment through climate change, the tropical equator has shifted closer to Antarctica.

Admirably outside of this genre of reaction, and far closer to the concept of allegory, is Sedimentary City (by Brit Andresen and Mara Francis). It conspicuously avoids the idea that massive change carries with it the certainty of disruption and erosion by focusing on the continuity of the city as a series of stratified layers of time and culture. Change, even massive change, does bring another layer encrusted over others, but it also illuminates what lies beneath it, with the Brisbane River as a line of physical stability. It’s worth the price of the catalogue just to look at these astonishing drawings – which are curiously disembowelled in the three-dimensional video by the separation of layers that need to be read together – asserting (for those who care) a hopeful future for two dimensions.

The most useful exploration of the fifty-year timeframe proposed as a speculative parameter by the creative directors, is Implementing the Rhetoric (by Harrison and White with Nano Langenheim). This offers a series of complex but entirely plausible strategies. It brings real underlying intelligence – a kind of practical iconoclasm – to the everyday, unchanging needs of cities: density, light and amenity.

Outside of this savvy realism, City of Hope (by Edmond and Corrigan) is perhaps the only entry that truly operates in the allegorical realm that the creative directors intended, as a type of extended metaphor or, at its furthest reach, like a parable. This hopeful world, entirely local in its geography (replete with a helpful locality map), is an allegory of rebirth, of regeneration, and an affirmation of what we know – as if to say that even with dramatic climate change, there will still be a spring. Their short catalogue text could be seen to be addressing a number of fellow exhibitors: “If in this turmoil we lose sight of our identity, we will sacrifice what is essential in us to our projection of the future. We should not sacrifice everything to the panic of our times.”

By any fair assessment Now + When offers a great deal to visitors, whether participating passively with the spectacle of its media, contemplating the Faustian pact between the media and the message, or digging into the content of the schemes that illuminate a hopeful When.

Carey Lyon is a director of Lyons.

FLYING OVER

Looking into the entry of the Australian Pavilion.

Image from Fraying Ground, by RAG Urbanism, Richard Goodwin (Richard Goodwin Art/Architecture), Andrew Benjamin, Gerard Reinmuth (Terroir).

External view of the pavilion.

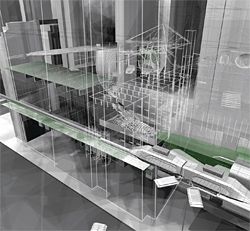

Terra Form Australis, by Hassell, Holopoint and The Environment Institute.

Entry to the upper level of the pavilion.

Looking down to the lower level.

View along the lower level.

Creative director Ivan Rijavec speaking at the opening of Now + When. Photograph David Pidgeon.

RACHEL HURST

Waiting in the queue to enter the enigmatic black box of the Australian Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale is a little like waiting in line at a 1980s nightclub. The buzz of expectation is there, the cues are encouraging – funky fluorescent orange lettering spelling out Now+When, gorgeously tricky catalogue with optical effects, and efficient door bitches marshalling patrons and handing out bright orange show bags. But also the anxiety that when you get in, there will be no-one there and the music will be all Depeche Mode or, worse, Duran Duran. The nostalgia continues inside, the pitch black of the two-level space illuminated dramatically by ultraviolet light and dazzling stereoscopic animated installations, curated by John Gollings and Ivan Rijavec. A soundscape by Nick Murray and Carl Anderson, at chest-reverberating volume, completes the setting.

Happily there are plenty of “clubbers” on the three occasions I visit during the Vernissage, moving gingerly through the space to the viewing positions dictated by suspended 3D spectacles. All are absorbed, not only in the camaraderie created by the dark, the funny glasses and the real risk of garrotting their neighbour with their spectacle cords, but more genuinely by the immersive experience and brilliant spectacle of the work on show.

The first component of the pavilion, Now, presents a vivid comparison between the urban edge and the mineral centre of Australia. Panoramas of Sydney, Melbourne and Surfers Paradise, glittering in a bling of night-time illumination, contrast profoundly with images of mining holes in the western outback. Beautiful and terrible at once, these gaping cuts in the landscape are paradoxically reminiscent of contemporary Indigenous depictions of intact native territory, and for many the most compelling images of the installation. Reviewer for The Australian Robert Bevan, in his unduly disparaging critique of Now + When, found the juxtaposition lacking in nuance, encapsulating what he called “the complacency of commercial design”. Though the environmental message may be so blunt as to be overly simplified, it illustrates the undeniable ambiguity of what constitutes beauty in an Australian context.

The second part, When, stitches sixteen separate visions for Australian cities in 2050 and beyond into a continuous 3D film. Each contribution is shown for thirty-eight seconds, without written or audio narrative. As the contributors are not identified in the film, viewers need to read brief synopses on the wall to identify schemes, prompting a kind of “guess-whodid- what” game among the architectural aficionados in the audience. The exhibited teams represent a broad cross-section of both architectural practice and academic partnerships, and the inclusivity of the curation is commendable, if only for encouraging a large contingent of Australian supporters. The ideas provide a diversity of fantastic macro-scaled schemes, consistent with the call from the curators to reimagine whole cities as “urban theatrical propositions … free from the tedium of current urban debate”.

These are futuristic, fanciful and seductive speculations and, like most crystal ball gazing, require a willing suspension of disbelief – not just in temporal and technological achievability, but also in reading of scale. For example, Terra Form Australis shows skyscrapers with heights equivalent to the length of Tasmania to illustrate its thought-provoking proposal for densification around an artificial interior coastline. Exaggerated verticality seems, if not obligatory, then pervasive – it’s the dynamic, optimistic axis visually, and these are unashamedly optimistic projections. Similarly, most of the scenarios emphasize transport, circulation and connectivity. This is most likely the result of digital animation being the sole representational mode: animations are essentially about movement, after all. What is disconcerting, however, is the homogeneous, almost leaden pace of the fly-throughs, a pace reinforced by the music, which threatens to undermine the up-beat nature of the visuals with its ominous undertones. Concepts and music flow in seamless time and space, inducing, perhaps intentionally, a hypnotic, “conscious dreaming” state. Though this heightens sensory sublimation in the observer, it also makes differentiation and genuine critical engagement with the ideas difficult. Elsewhere, Sarah Treadwell has described this effect as a “form of cerebral paralysis induced by the flaccid movement [of fly-throughs] that registers neither agitation nor its termination.”1 She notes that fly-throughs tend to “construct ground as smoothly pictorial” and despite the weight of rendering (which in Now + When is consistently impressive), “seem not to get caught up in considerations of gravity.” A loosened foothold on the earth may be an inevitable consequence of the fly-through, and this is tackled in a number of ways by various schemes: the floating metropolises of the Avatar-blue Oceanic City and earnest cellular composition of Saturation City, the hovering horizons and billowing urban quilts of Multiplicity and How Does It Make You Feel?. Only a minority, like the layered grainy collages of Sedimentary City, focus explicitly on “ground” as a defining element of the Australian setting, though it is accentuated by Now’s outback vistas. The number of schemes that deal with gravitas are arguably fewer – even those depicting post-apocalypse scenarios, like the stern inhabited aqueducts of Aquatown and sci-fi comic images of Mould City, are buoyant predictions for future livability.

At the opening of the pavilion, Rijavec likened the other-worldly depictions of some of the schemes to the immediate context of Venetian architecture – the ethereal imaginary realms of baroque frescoed ceilings and Italian religious art. Like those precedents, When uses transcendent images to project beyond the turmoil of the everyday, to inspire hope and belief in some higher authority who will solve the dire problems of the present. The mesmerizing glimpses of heaven that the consummate technicians of seventeenth-century trompe l’oeil, such as Tiepolo and Andrea Pozzo, were able to conjure in the service of both celestial and earthly versions of Christian authority were undeniably a form of propaganda. One might ask if a similar task remains for contemporary architects, to provide equivalent comfort and hope. Inspiration – yes; spin doctoring – probably not, if the tenor of the rest of the biennale can be used to judge, for along with the expected array of exquisite, inventive “big projects”, director Kazuyo Sejima’s curation elicited an unmistakable preoccupation with sensitive but pragmatic problem solving, rigorous analysis and re-evaluation of traditional modes.

Moreover, like the theatrical creations of the baroque, When has an undeniable obsession with striking formality and compositional consistency, whether based in crystalline, biomorphic or good old-fashioned architectonic language.

Other stakeholders in urbanism – planners, social demographers, ecologists, et cetera – might argue that that is a misrepresentation of how good urbanism is generated, but the associations provoked by the schemes are rich. There is everything from Renaissance and Beaux-Arts ideal city plans in the gorgeous psychosexual pastiche of Edmond and Corrigan’s City of Hope to twentieth-century delineator Hugh Ferris’s futuristic utopias in Fraying Ground, to glossy sex toys (no names, no pack drill), in varying degrees of appeal, fascination or good taste. The collection is a visual smorgasbord of contemporary ideologies, architectural languages and representations, and if there are accusations of derivative imagery – of Archigram, Superstudio, Coop Himmelblau, Lebbeus Woods or (according to Bevan) MVRDV – then the Australian exhibition was by no means alone. Within the fervent drive of the whole biennale event to display the latest new thing is the glaring recognition of how hard it really is to do something genuinely original. Along with the selection of the modest, craft-based pavilion of Bahrain as Golden Lion winner and Sejima’s curation generally, this raises the question: why not concentrate on doing unoriginal better?

The biennale’s benevolent mantle People Meet in Architecture is curiously hard to identify in Now + When, despite this being a – the – critical aspect of good urbanism. Only a few animations were populated with plausible human activity of any detail or intimacy. Ironically, it was the rigmarole of negotiating the space and 3D spectacles that picked up the theme in a relaxed manner, unlike some of the more didactic, hands-off pavilions or those that forced deliberate interaction. A legitimate defence is that the curation and content of the Australian entry was determined before Sejima’s theme was announced. Any informed urbanist, however, knows the perils of macro-planning without attention at the pedestrian, people level of cities. Michel de Certeau warns against taking a distant view of the city and becoming “an Icarus flying above [the] waters, (who) can ignore the devices of Daedalus in mobile and endless labyrinths far below.”2 So is it the fly-through and its divorce from the ground plane that is responsible for the dearth of engaging human activity in the When anthology? Or is it a mismatch between the desire for spectacular visionary concepts expected of contributors and the essentially conservative nature of how we occupy real cities?

Perhaps my disappointment at the lack of demonstration of the on-the-ground benefits of all these courageous proposals was heightened by spending three days beforehand in the fine-grained city of Padova, trying to observe and record what makes it such a vibrant, satisfying place. Crucially, more than a quarter of its population are students, but physically the city delights with its balance between typological constancy, expressive individuality and intimate human scale, at every irregular corner and warped turn of the street. The immediate setting of Venice also provides a relevant critique of Now + When, as it did for many of the pavilions in the biennale (notably the UK’s Villa Frankenstein, which used Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice as a pivotal ideological launching point). Venice is a city founded on a big idea, an initial imaginative leap of faith which remains both lucid and ludicrous to this day. Yet what makes it the city to inspire the likes of Ruskin, Calvino and the twenty million tourists who visit it each year is the close detail, the incremental, worn, idiosyncratic manipulation of that overarching template which enriches urban experience at the walking, talking, sitting, eating, watching, human level. If this aspect of urbanity was underplayed in some of the work on show, so too was the sense of any regional inflection. Apart from background settings of the major Australian cities, many schemes could have been strategies for anywhere. Notable exceptions were Terra Form Australis, Sedimentary City – the scheme with the (shamingly) singular direct reference to Indigenous occupation – and the Melbourne–Hobart bridge of Island Proposition 2100. Positive spin would use this as evidence of Australia’s international perspective and interest in solutions with global application. Bevan’s critique, however, saw it as out of step with prevailing preoccupations with contracted, localized, interstitial, place-specific architectural advocacy.

But if the bravura and downright fun of the Australian pavilion lacked some of the poignant gentle observations of others, at least it wasn’t earnestly pedagogical in the manner of the French or Danish contributions, which were serious one-stop condensed courses in urban design. I am not convinced by Rijavec’s confident statement at the opening that the When proposals “lack the sanitized perfectionist depictions of other exhibits”, given the gleaming, fastidious nature of most of the Australian schemes. They are, however, blatantly entertaining. Maybe I misheard him in the euphoric buzz of opening morning …

These criticisms aren’t intended to be carping. The Now + When exhibition is a slick and intelligent snapshot of Australia and its architectural capabilities, with evident concerns for urbanity, environment, climate and place. As a biennale “virgin” and architectural educator, I found the event sensational, literally and intellectually, and probably one of the most intense and effective forms of professional development any architect could undertake. Now + When, with its stunning immersive impact, would undoubtedly have thrilled those in a position to add financial support to the continuation of this important event, and its internalized black-box approach countered the outdated dreariness of the building itself, which sits poorly against most other pavilions in the Giardini. Many of these are worth architectural detours in themselves, no matter what is displayed inside. As John Wardle quipped, “my favourite pavilion is Venezuela and I can’t even get in there!” The next step perhaps is to have a building, maintenance and support program which tangibly demonstrates Australia’s architectural presence and substance, and that is worthy of the efforts of Gollings, Rijavec et al. So that having made a spectacle of ourselves, we can now concentrate on the closer view – a bit like waking the morning after from the 80s nightclub and wishing the lighting had been a little less theatrical and a little more revealing.

Rachel Hurst is a senior lecturer in architecture at the University of South Australia.

Images of all exhibited schemes are presented in Architecture Australia vol 99 no 5, September/October 2010. The catalogue is available from the Australian Institute of Architects.

1. Sarah Treadwell, “Petrification and the Architectural fly-through” in Drawing Together: Convergent practices in architectural education, Proceedings of 3rd International Conference of AASA ed K. Holt-Damant & P. Sanders, (Brisbane: QUT & University of Queensland, 2005), at www.architect.uq.edu.au/aasa/public/papers.html

2. Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. S. Rendall, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 92.

PEOPLE MEET

Blueprint by Korean artist Do-Ho Suh and Suh Architects, in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni della Biennale.

Students at Learning Architecture, the Macedonian exhibition, curated by Minas Bakalcev and Mitko Hadzi-Pulja (MBMHP). Photographs Mirjana Lozanovska.

MIRJANA LOZANOVSKA

It is easy to be cynical about the spectacle and extravaganzaof the Venice Biennale. When the paparazzi surrounded Sejima and Nishizawa for their conversation with film director Wim Wenders, thoughts of Hollywood and the “starchitect” became real and visible. And yet this cynicism is superficial because as an architectural community we have put value on Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion and Konstantin Melnikov’s Russian Pavilion, produced in similar forums. It is easy also to be horrified by the excessive tourism in a city like Venice, and yet this tourism is partly an outcome of the profound and compelling literature and cinema that, as tourists, we carry with us on our way to such cities. Globalization and the consumption of culture do not easily divide the beautiful from the grotesque, the valuable from the trivial, and architecture like all other cultural productions finds itself swept up by people’s desires and fictions.

These are just two threads of the theme of the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale, People Meet in Architecture, developed by Japanese architect Kazuyo Sejima. Explicit criticism in architecture journals about the recent lack of architectural focus of the biennale were put aside in anticipation of a director who is an exemplary architect, who was awarded the 2010 Pritzker prize (in partnership with Ryue Nishizawa, SANAA). Sejima’s theme is not unlike her way of speaking English or her mode of architectural design – qualified by a linguistic and spatial openness. And yet with characteristic thinness and linearity, it firmly inscribes an aesthetic position and an agenda that is not blurred, even if open.

National and architectural firm participants exhibiting in the Corderie dell’Arsenale, the old brick buildings of the ropemaking factory of the Venetian navy, were asked to express the character of the existing space in their projects. In this sense, the architects are the people as they encounter existing architecture. Displaying the components and materials used in their workplace – 1:1-scale facade sections, stone components, tiles, colour samples and many models – Studio Mumbai Architects produced a weighty presence of the matter that engaged the viewer corporeally. A range of models, from small shapes literally thumb-printed to large-scale models testing the digital geometry, circulation and structure, and images of the 1:1 construction model, presented the design process of Toyo Ito’s Taichung Metropolitan Opera House. Both these exhibits engendered the viewer as architect because these were not artefacts remade for exhibition but the tool kit of the architect.

Also playing with the idea of the architect was the Japanese Pavilion in the Giardini – a fully detailed dwelling and studio space at doll’s scale. Because the structure was suspended in a void in the floor, the viewer was invited to enter from below such that their head peered into the space, and then from above on the next level. It was enchanting and contrasted with their other component, which explored the 26-year life cycle of buildings in Tokyo in response to the 50-year anniversary of metabolism. In the Palazzo delle Esposizioni della Biennale, the collaboration between artist Do-Ho Suh and Suh Architects created an artistic mediation of house, home and architectural representation. Entitled “Blueprint”, it comprised a blue -tinged elevation drawing of layered facades (the artist’s house in Korea, his New York townhouse residence, and a typical Venetian villa), which was placed on the floor and constructed from laminate panels that were rubber -soft underfoot. This was reflected by a translucent, blue, gauze-like fabric 2010suspended from the ceiling, meticulously patterned and hand-sewn to form a 1:1 reproduction of a facade (the New York townhouse) in relief, such that indentations were to scale. If cerebral ideas about memory, shadows and representation could be transferred into experience, this installation came close. Other pavilions (Russian and Dutch) explored this theme of the architectural presence of the past through the plight of many existing unused buildings, especially industrial buildings – beautiful and yet left vacant or demolished.

The pavilions of Estonia and the Republic of Macedonia produced a white field of housing typology (Estonia) and spatial situations (Macedonia) that visually contrasted the aged masonry at the Arsenale, and presented the idea of “many” people in architecture. Under the creative guidance of Minas Bakalcev and Mitko Hadzi-Pulja (MBMHP), the Macedonian pavilion, Learning Architecture, presented the results of 101 first-year students. Each student developed a program and space for three people, generating many “people–architecture” situations. At the opening, sixty-five students in red T-shirts joined hands and encircled the large white field, illuminated by the light from three arched windows. This was inspired by the “oro”, a traditional dance that through ritual produces a primal and primeval space of individuals in a collective shape. Architecture as white field is always animated and created by human subject(s) as one and many, and in the final model expressed in the trace of black shadow figures.

It is because I enjoyed so much of the biennale that the awarding of the Golden Lion for best national pavilion to the Kingdom of Bahrain was perplexing, especially as two of the judges might have had a different impression. The pavilion presented three “fishermen’s huts”, described by the team as “architecture without architects”, purchased and reconstructed in the Arsenale – contradictions already announced in this huge task supported by huge finances – against their evident popularity as resting haven. Some Bahrainis are deeply concerned about the sea in which their island is located. Not many, because the actions and realities are testimony to a different history of oil, urban development and land reclamation, making the “we” in the text confusing. More contradictions. This exhibit is a trace of a lament for a romanticized past that possibly did not exist. The problematic representation of others might have been overlooked if a potent poetics proposed a different future. However, the proposal is for a new waterfront strategy, one promoted by a fashionable global economy of cultural tourism. How and whether such “fishermen’s huts” would feature or survive in this new agenda is not explored in the exhibition. The huts have become by default artefacts in a museum, announcing the end of their spontaneous construction.

It is not an easy task to produce architectural exhibits. They run the risk of being too visual and trying to be art or graphics, or too representational and textual, or just too abstract and/or confusing. In 2010 participants answered Sejima’s call and produced pavilions and exhibits that were experiential, spatial and corporeal. Many inspire new ways of doing architecture and leave you with much to think about.

Mirjana Lozanovska is a senior lecturer in architecture at Deakin University.