PHOTOGRAPHY Claudio Franzini

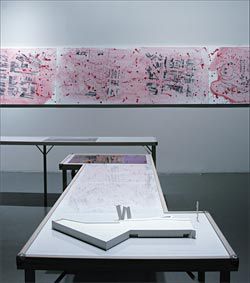

Detail of Micro Macro City in the Australian Pavilion. The table showing the Marion Cultural Centre by Ashton Raggatt McDougall is seen in the foreground, with painting by Louise Forthun on the wall beyond.

Overview of the upper-level exhibition space seen from the pavilion entry, with Louise Forthun’s painting to the left and one of the two thematic video loops at the rear.

View of the pavilion’s lower level, showing the finely crafted fold-out tables, large thematic photographs and thematic video loop.

Looking along the length of the lower exhibition space.

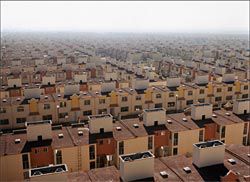

Mexico City Ecatepec, Mexico, 2006. Photograph by Scott Peterman, courtesy Miller Block Gallery, Boston.

Plein Street, Down Town, Gauteng, Johannesburg, 2004. Photograph by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin.

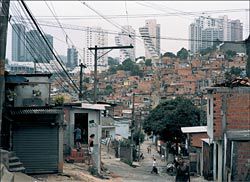

Favela Paraisópolis, São Paulo, Brazil, 2001. Armin Linke, courtesy Galleria Massimo De Carlo.

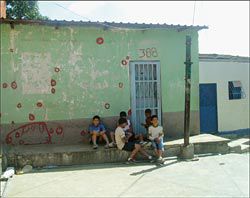

Caracas, Venezuela. Photograph by Art Rothfuss III.

Maryam Gusheh reviews this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, considering the Australian Pavilion alongside the wider themes and exhibitions.

On arrival in Venice, the thirty-hour haul from Sydney – further extended by a nervous search for lost luggage in Milan airport – seemed like a carefully choreographed journey, deliberately prolonged in order to heighten the sense of entry into this fantastic setting.

Riding towards the Rialto Bridge at dusk – and despite my innate scepticism towards this impossibly picturesque scene – Venice seemed truly enchanting.

The mesmeric allure of this ancient city lies in its overall urban ambience, the richness of the urban ensemble. To recall John Ruskin’s celebration of Venice, it is the contiguous rows of modest houses along the Venetian streets and the banks of its canals that weave the urban fabric together, rendering it irreducible to the sum of its great palaces, civic and religious buildings.

Labelled as urban heritage and formally preserved, these homes have come to serve more transient occupants, looking on as Venice is transferred from permanent inhabitants to those who pass through.

Over the past four decades, the city’s population has halved, and it continues to diminish at an alarming rate. While receiving over twelve million visitors per year, it is estimated that within twenty-five years Venice will be without Venetians.

Such a projected disjuncture between the city and its inhabitants presents an engaging tension with the main concerns of the Tenth International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Architectural Biennale. With a focus on the relationship between urban form and the contemporary realities of everyday urban life, the exhibition considers the social role and value of architecture within growing cities.

The main show, City. Architecture and Society, occupies the Corderie of the Arsenale. The grand volume of the former naval ropemaking factory provides a spectacular setting for a sequence of multimedia narratives about sixteen global “hot spots”.

These include the world conurbations of Tokyo and Mumbai, São Paulo, Cairo and Shanghai; New York and London; the smaller European centres of Barcelona and Milan; and familiar sites of political renegotiation, Johannesburg and Berlin. Through individual profiles and comparative readings, the exhibition charts the reality and impact of massive global urbanization on some the world’s most populated centres, highlighting diverse regional particularities as well as the levelling effects of globalization and national interdependencies.

Curated by Richard Burdett, Professor of Planning at the London School of Economics, the Biennale’s focus on cities is an ambitious attempt to relate architectural production to a complex range of social, political and environmental fields. His urban tales are packed with statistics and data, presenting dramatic social challenges: overcrowding, population increases, lack of infrastructure and resources, urban poverty and crime.

Architectural innovation, Burdett suggests, should arrive through a deliberate commitment to social agency and the shaping of democratic everyday environments.

The exhibition cites a diverse range of successful urban interventions, operating at the level of policy, infrastructure, civic buildings and landscape. The Latin American capitals offered some of the most interesting examples – Lina Bo Bardi’s stunning and socially vibrant conversion of São Paulo’s old drum and fridge factory and the subtle spatial adjustment and restructuring of the barrios (shantytowns) of Caracas were enough to instigate the desire for an instant Latin American pilgrimage.

But this approach is not entirely new. The Biennale’s retreat from the architectural object, and its privileging of the real, the ordinary and the everyday, alludes to familiar postwar debates – most famously advanced by activist groups such as the Situationists – where reference to the spontaneous, festive and playful dimension of everyday life was deployed as a motivating force for a revolutionary revitalization of urban space. The city and the urban situation, it was argued then, offered the greatest hope for social transformation and the realization of a liberal life.

It is precisely this same ordinary fabric that forms the content of Burdett’s show. But here, the ordinary appears sensationalized and thereby risks losing its political intent.

Beautifully designed, the exhibition is legible and visually arresting. Quantitative facts and figures are reframed as stunning graphic displays. Powerful digital simulations spur us to imagine fantastic scenes: to picture the entire earth, at night, from outer space.

This unearthly viewpoint is also a characteristic of the photographic content of the show. Large, glossy and backlit, aerial images offer intricate views of the featured cities, capturing specific spatial relations while also abstracting such particularities into fields of colour and labyrinthine pattern. This ambiguous quality underpins the unsettling allure of these photographs: their capacity to foreground contemporary urban challenges – poverty, economic disparity, overwhelming density and natural disaster – while also offering aesthetic delight.

In these images, as in the broader exhibition, visual seduction is at play. Here, oblique aerial shots of shantytowns curiously instigate a sense of nostalgia for a pre-industrial past; a frontal view of a decaying housing block, its grid fenestration carefully framed and cropped, appeals to the modernist aesthetic of patina and dilapidation – the aging drapery adding graphic richness through colour and pattern. Likewise, a bird’s-eye view photograph of a flooded town serves to flatten the image into figure and ground, reproducing the effect and aesthetic of an abstract painting, and so on. Such implied tensions – between the documentary role of the image and its aesthetic function – underscore the ambiguous allure of these photographic displays, which at their best suggest the contradictions inherent within contemporary urban environments. However, any consideration of “everyday life” when used as a critical construct always entails a deep distrust of spectacular formalism, not only of the architectural object, but also its representation. And it is precisely this added emphasis that, to me, undermines the logic and political potency of Burdett’s argument.

The international contribution to the Biennale, as displayed within the national pavilions at the Giardini di Castello, sustains a loose affinity with the themes raised by the main show. The most engaging exhibitions extend Burdett’s narrative through more detailed architectural representations. However, for the most part, the implied focus on the contemporary urban situation provokes a tangential discussion of architecture and approaches to architectural representation. In its tenth year, the Venice Architecture Biennale seems to be curiously without the fabric of architecture.

The Australian response, Micro Macro City, resists this tendency, insisting instead on a conceptual relationship between architecture and emerging urban situations. Finely detailed, irregular fold-out display tables are arranged through the pavilion, gently marking a viewing path through the space. Each holds the documentation of highly specific urban portraits and aligned architectural projects. Eight suggestive key words accompany thematic groupings, mediating a conversation between architecture and the city. Curated by Shane Murray and Nigel Bertram, architects and architectural academics at RMIT University, the exhibition is premised on two interrelated assumptions: that the physical environment acts effectively as an index for societal change; and that the fluid sites of urban transformation are of interest due to their potential to host new programmes and social relations.

In their contribution to the Biennale, Murray and Bertram invite us to consider: Can emergent urban environments offer innovative strategies for architectural design? Does the designed architectural fabric provide an alternative yet equally intricate register for social, economic and cultural change?

What is the social agency of these carefully crafted and highly refined works of Australian architecture?

The selected architectural projects and sites are represented through meticulous and intricate plans and three-dimensional views. For certain projects a white massing model communicates the overall form of the building. A modest set of photographs illustrate certain moments within the architectural projects, adding a touch of colour to this deliberately pared back visual narrative. Commissioned multimedia artworks respond to the exhibition themes, offering atmospheric impressions of ordinary life in Australia. As an assemblage, the work is subtle, gently intriguing and invites careful attention. The curatorial direction is intellectually rigorous and insightful, if at times illusive. Murray and Bertram’s ambitious and laudable effort to resist banal categorizations and generalized assertion, has at times led to overly abstract thematic groupings that, although suggestive, arguably fail to communicate the richness of their thinking. Such ambiguities aside, the exhibition’s deliberate antispectacular stance and its privileging of the discipline of architecture as the site for both research and practice makes a vital contribution to the Biennale, engaging with the theme while subtly critiquing its associated limitations.

I returned home to Sydney via a two-day stopover in Tehran – to see my family, stock up on culinary necessities, and the like. Battling my way around this familiar urban chaos, I could not help but think of the great set of statistics that Tehran could offer Burdett: over twelve million in population and near zero tourism! The highest level of air pollution in the world, even more polluted than Mexico City. Tehran is seriously On Line! Farsi is the third most commonly used language on the internet; and the city also scores high on the number of annual plastic surgeries (beating LA). And, we have been told, Tehran is resolving its energy crisis quite effectively! Statistics aside, Tehran provides a fascinating alternative to the global “hot spots” showcased in Venice. The political changes of the past twenty-five years have transformed the urban quality of this city. The displacement of public life to the domain of the interior, for instance, represents a unique contemporary urban phenomenon. During my short stay, everyday warm moments came in the company of friends and against the background of domestic interiors, places of work, or the unexpected walled gardens that are scattered throughout the city.

Catering to complex programmes, both private and public, many of these interiors sustain a vital sense of social presence and resist the explicit political pressures that hinder public life. The ordinary life of Tehran, its everyday social situations, it seemed to me, would resist the totalizing gaze of even the most penetrating aerial photographs.

MARYAM GUSHEH IS A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES.