What is it to exhibit architecture? Charles Rice considers the ‘Hoax’ Australian Pavilion for last year’s Venice Biennale and speculates on what it might mean for Austalian architecture.

The Virtual Australian Pavilion for the 2004 Venice Biennale of Architecture, designed by Tom Kovac. For John Gollings, the aim of the architectural hoax was “to create confusion, debate and embarrassment to the public bodies who cannot reach agreement”.

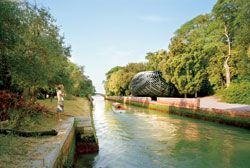

View from canal, with the pavilion shown in the late afternoon light of a Venetian late summer’s day.

Night views of the pavilion interior. Curated by Andrew Benjamin, the exhibition was designed by David Pidgeon.

Night views of the pavilion interior. Curated by Andrew Benjamin, the exhibition was designed by David Pidgeon.

The exhibition by day, complete with visitors and sunlight filtering through the external structure, one of many angles possible while navigating the website. Images by Daniel Flood and David Liao.

The question of what to do about an Australian presence at the Venice Biennale of Architecture has once again been raised. The Australia Council, which controls the Australian Pavilion and organizes the Australian presence at the Biennale of Art, refuses to recognize architecture within its portfolio. This year, a group of individuals led by John Gollings, and including Davina Jackson, Andrew Benjamin and Tom Kovac, took matters into their own hands and produced a Virtual Australian Pavilion containing a curated exhibition for the 2004 event. The pavilion set up something of a hoax - a virtual presence that could be mistaken for a real one for those not in Venice. CDs and a catalogue were included in Venice press packs, and the pavilion exists as a website, www.venicebiennaleaustralia.com.

But beyond the putative hoax, a way into the thorny issues of governmental responsibility for such events can be found in Andrew Benjamin’s “notes” that bind the exhibition together. Autonomy is the concept Benjamin uses to think through architecture’s contemporary cultural agency. He introduces it in relation to art, where autonomy is secured neither through pure aesthetic value nor through resistance in the form of anti-art. The former guarantees art’s commodity form, while the latter instantiates a simplistic negativity. Benjamin argues that what makes art autonomous is its refusal to be neither simply commodity nor simply anti-commodity. This productive tension gives art its particular critical positioning within culture. When we think about this issue in relation to architecture, the Australia Council’s stance on architecture - that it is properly a part of trade and commerce portfolios - can be seen in a new light. The issue is not that they should take on architecture, therefore making architecture like art and paradoxically making it more like a commodity through a reification of aesthetic values, but that in their refusal of architecture a new possibility emerges for the presentation and critical discussion of architecture, one that begins to be taken up by the Virtual Australian Pavilion.

What follows from this is not a question of whether architecture is a cultural or commercial act - it is cultural because and at the same time as it is commercial - but the idea that an architecture biennale can be distinguished from an art biennale. The distinction turns around what “presence” might mean in the context of an exhibition. While we might argue that both art and architecture require presence, art’s presence is always framed by exhibition, whereas architecture’s is not. This is not an argument against the exhibition of architecture. Rather, it is one that tries to understand what specific conditions attend the exhibition of architecture. This is where the agency of a virtual pavilion is an interesting issue, and where the idea of the Virtual Australian Pavilion being a hoax annoyed me a little. I can understand the immediate political motivations for such a larrikin posture, and the pavilion does indeed “convince”, nestled in the late afternoon light of a Venetian late summer’s day. But in the very reality of the virtual pavilion, possibilities for the exhibition of Australian architecture are opened beyond the idea that, in future, it should be a real presence in Venice. The Virtual Pavilion allows us to rethink presence, and in doing so, to open up the productive difference between the exhibition of art and the exhibition of architecture.

This productive difference turns around the status of text or, more particularly, the way in which the curatorial text has the possibility of interacting with images in a way that is more integrated than can be managed in a traditional “spatial” exhibition. While the pavilion design explicitly takes on the imperative of rethinking the space of exhibition, the effect of the exhibition can only be measured via the computer interface. In this context, what is most successful about the virtual exhibition is the discussion of Australian architecture that it stages. Benjamin’s curation is, for want of better terms, essayistic rather than imagistic. He begins by refusing the easy solace of a specifically “national” identification of Australian architecture, the problem implied in the “real” Australian Pavilion in Venice. Instead he discusses a series of projects through the more complex and contested themes of autonomy (as a frame that sets out the possibilities for exhibition), the public (as an explicit refusal of “the private house” as icon of Australian architecture) and site (as contested, as already marked). He works through these themes in a dialogue with the selected projects.

The logic of project selection - from architects including ARM, Durbach Block, FJMT, Merrima, Minifie Nixon, Lab Architecture Studio, Room 4.1.3, Terroir,Woodhead and Wood Marsh - refuses any sense of a “representative sample” (can we really speak anymore of different regional “scenes” in Australian architecture?). Instead Benjamin argues out these themes as crucial in understanding what is at stake in the contemporary practice of architecture in Australia. And this is not simply to “put Australian architecture on a world stage”, as if, in not being in Venice in some form, Australian architecture ceases to exist or falls into a lesser regard. Rather, the value of the exhibition is in the exemplification of a way of thinking about and discussing architecture that has ramifications beyond the particular projects discussed.

If our thinking is still preoccupied with the global “opinion” of Australian architecture as a whole, the curation of the exhibition in the Virtual Australian Pavilion, begins to reframe such concerns in a significant way.