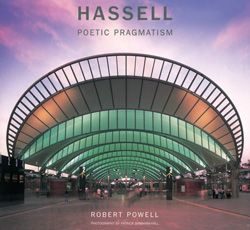

HASSELL POETIC PRAGMATISM

Robert Powell and Patrick Bingham-Hall. Pesaro Publishing, 2003. $50.

In its engaging coverage of one of Australia’s most prominent corporate practices, this book veers more to the pragmatic than the poetic. Images outweigh text in describing the featured projects, with most of the photography by Patrick Bingham-Hall, who is also the editor and publisher. Robert Powell’s concise introductory essay leads the reader through the origins of the practice, its development since its formation in Adelaide in the late 1930s, and the ideas and influences that underpin the selected works.

These are virtually all from Powell’s “third generation” of the practice – and from the period over which Bingham-Hall has been documenting Hassell’s built works.

The visual anthology of projects charts the breadth of Hassell’s expertise. It spans architectural design of all scales and a broad range of building types, landscape design, interior design, and urban and landscape masterplanning. This is represented by accomplished schemes, suitably recognized in the bevy of awards listed in an appendix.

Powell suggests that the guiding principles of the practice are to recognize diversity, to embrace pluralism and to harness collaborative interaction. He also points to the effect of designing to suit place and implies that each node of the practice actively embraces approaches that match the local imperatives of their respective cities: the Brisbane office’s focus on place and climate, the lyrical formalism of the Sydney office, and the knowing experimentation with collage and overlay of form, surface and space in Melbourne. To this is added the influence of the principal directors in each location: Tim Shannon in Melbourne, Christopher Wren in Brisbane and Ken Maher in Sydney.

This is supported by signature projects including the crisp, structurally derived forms of the Olympics Railway Station and the Qantas terminal at Sydney Airport; the layered formalism of the Commonwealth Law Courts in Melbourne; and the Hall Chadwick Centre in Brisbane with its emphasis on sustainability and energy conservation.

Despite this diversity, there remains a sense that the disciplined interpretations of Modernism that distinguished the early years of the practice still hold sway. Set into the margins of the introductory text are illustrations of selected formative works including the National Insurance Company of New Zealand in Adelaide (1962); Balm Paints, Rocklea, the Queensland RAIA Building of the Year in 1966; and the Weir Restaurant, Adelaide (1968). These offer glimpses of a disciplined and refined late Modernism which still reads through in projects such as the Northern Metropolitan Institute of Tafe, Heidelberg, and the National Institute of Dramatic Art, Sydney – the first and last buildings in the suite of works represented in the main body of the book.

The straightforward tone of the text avoids the obfuscation that mars many contemporary architectural publications. The essential character of the architecture rings through, with the poetics of the title residing largely in the better known works.

Bingham-Hall’s photographs present the buildings and landscapes in their own terms without converting them into objects of photographic art. The book demonstrates the way that Hassell has held true to its basic principles of design and practice as it has grown and diversified. Additional coverage of the practice’s formative early work would have made this clearer still. And while the list of awards is helpful, a bibliography would be a valuable addition.

Finally, I suggest that the work can be described and analyzed in its own right. It is not necessary to associate projects with internationally known examples in order to elevate their standing or significance. The Olympic Railway Station is recognized as a significant building and does not need to be associated with the Waterloo International Terminal – a project of a completely different scale, setting and execution. Neither can a convincing parallel be drawn between the Roma Mitchell Arts Centre and Stirling and Gowan’s Leicester Engineering building, a building of a quite different era, formulation and programme.

In Ken Maher’s words, “the future will be built upon our best work.Work which is intelligent and responsive to its setting and the aspirations of its people.” A pragmatically poetic way for the Hassell practice to continue to move ahead with ambition and intent, sustained by the integrity that comes from the cumulative experience and achievement illustrated by this book.

MICHAEL KENIGER

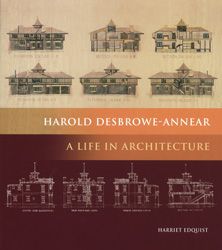

HAROLD DESBROWEANNEAR

Harriet Edquist. The Miegunyah Press, 2004. $69.95.

When I lived in Melbourne, architectural history seemed elsewhere. Now I find more to admire with each return visit. Some years ago my eye was caught by a photograph of the living room at Ballangeich (1910) in Alphington, in an article in The Age. Last August an article on Chadwick House (1903) in Eaglemont, one of a trio designed by Harold Desbrowe-Annear (1865–1933), transfixed me again. Peter Crone then showed me over this painstakingly restored house in February, on a blazing hot day, when Desbrowe-Annear’s innovative, century-old ventilation system kept the living room cool.

Although Desbrowe-Annear was described as a pioneer of Modernism by Robin Boyd in 1947, Harriet Edquist’s new monograph is the first to fully research his career. It seems apposite that she’s professor of architectural history and head of the School of Architecture at RMIT, where he founded the T Square Club in 1900; and that her book is published by Miegunyah Press, named after the Toorak house that he altered in 1920.

It’s a good book for the lay reader, and for architects and their historians, and is more informative and enlightening than coffee-table tributes. It includes much of Desbrowe-Annear’s personal life – gleaned from the letters and biographies of clients and friends – as well as his professional development and architectural achievement.

In common with Arts and Crafts architects elsewhere, Desbrowe-Annear had a strong sense of place – designing houses appropriate to their locations with interiors, built-in furniture and other furnishings and gardens designed to be all of a piece.

Edquist charts Desbrowe-Annear’s experimentation with domestic design and argues that his larger houses commissioned by wealthy clients in the 1920s, which alienated many admirers, remained full of new ideas. In doing so, she affirms his reputation as one of the most innovative architects working in Australia in the early twentieth century. Additionally, I know now that the Ballangeich living room that first captivated me was thought by the artist John Longstaff to be the nicest room he’d ever been in.

COLIN MARTIN