|

Looking south-east along the bedroom wing to the living zone and deck. Image: John Gollings

Looking north towards the rear of the house, with the main bedroom projecting over the slope. Image: John Gollings

Looking north-east to the rear of the house. Image: John Gollings

Looking east from the bedroom wing, with the living wing and deck at far left and master bedroom and kitchen zones at far right. Image: John Gollings

The living area from beside the kitchen. At left is the main entry and the passage to the bedroom wing. Image: John Gollings

Living and dining zones from the kitchen. Image: John Gollings

|

|

Bachelard wrote that the house “holds childhood … in its arms.” With Kirsten Thompson’s account of how both she and the clients became first parents while this house was being designed in mind, I wondered how to approach the review of a house so new. Like Edmond and Corrigan’s Athan Residence, this house is designed to cradle dreams and hopes within a clearly ordered choreography of family life. As I wandered around and experienced the different modes of containment, I imagined the life of a family unfolding in these spaces.

This reminded me of images of the great Lina Bo Bardi’s own Glass House in Sao Paolo. Photographs taken in 1951 show a horizontal slab of space, glazed on three sides and cantilevered over vegetation on the fringe of the city. This room has a mosaic floor, a round dining table and chairs, a few modern easy chairs, an ornate inlaid table, and a sprinkling of books lying flat on the glass shelving system that she invented to avoid interrupting the space. Photographed in 1993 (after her death in 1992), the house is sunk below the treetops in an established suburb. The room has filled with the accumulations of her career as an architect and stage designer. Added to the pieces shown in 1951, there are rugs on the floor. Reading lamps. Chairs ancient and modern. Some chairs are stacked with folios. Curtains! Sculptures! Plants and bowls of the seeds of tropical trees. TV! And standard library shelving groaning under the weight of books stacked back-to-back. Paintings, religious and profane. The obvious ways of being in the space have multiplied from three settings for dining, sitting and reading, to twelve.

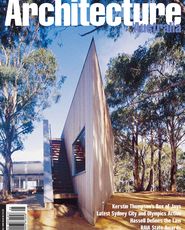

Standing in the currently highly resonant space of this new house, I construct a picture of its ‘completion’ four decades hence. But let me begin at the beginning: imagine being on a bull-nosed spur that projects from the Otway Range towards the half-moon water and sand of Apollo Bay. Imagine owning this spur. Picnics. Dreams of extending the hanging moments of lazy afternoons into a lifetime. Finding an architect who understands the site, empathises and can surmount the pragmatics of fire control, knowing that for you this bare crest between the trees is the place where the house, that tangible diagram of your dreams, must be!

That architect brings dreams of her own, a love of the Casa Malaparte, and a shrewd understanding of the micro-climate and what can be built 200 kilometres away from supervision. Metaphorically she strikes a blade into the hill along the north-south axis of the spur, and this cut into the earth becomes the spine-wall of the house; seemingly razor sharp at the northern, arrival end and bending slightly towards the west as it comes free of the ground to the south. At this precise moment of leaving the brow, a living space projects eastwards over the falling flank of the spur, angled up to the northern sky and closing down tight on the views to the south. A separate space thrusts away westward, completing the curve of the wall. From the northern razor edge, a ‘snake’ of rooms follows the fall of the ground along the western face of the wall, stopping to allow entry at the point of projection. Here, on grade with the main level of spaces projected over the nose of the spur, is the fulcrum of the house, both in form and in program. This entry space and kitchen seem to form a cockpit around which scenes of future life pivot. The spaces of the house and the landscape spin around this focus. While preparing, cooking or washing up, the owners are in full contact with the north light-catching, south view-embracing, living space. The brow of the hill is sucked into this space via the northern deck to which this room opens. A seating and storage ledge, flush with a timber deck projected over the brow, steps down into the room; the threshold marked by a solid horizontal light baffle at door height; a slatted sun baffle continuing outside. Here, a more intimate scale suggests that you sit and contemplate.

The floor surfaces are Armourply, imparting a vibrant organic patterning. At the opposite end of the room, the roof sections down to a square picture window; bracketed by the fireplace so that you can sit facing fire and view. A long window seat stretches below horizontal glazing, paralleled by a long heavy timber table. Games, meals, dozing over books. Also from this cockpit, the cooks can see the western view and the barbecue deck that wings out from the house on the contour behind. Offset to the left, the spine wall angles in towards the focal kitchen. Looking back, the strip windows in this wall afford an unexpected ground-level view to the formal entry path along the eastern flank of the wall.

To the left again, gum-booted arrivers can be debooted and marshalled up the stairs into a bathroom in the ‘snake’ of rooms. Really this is a room with a bath in it, easily encompassing tribes of cousins and their minders. Washed, they can be despatched up the passage to bed. Or rewarded with a visit to the fire as the grown-ups grow philosophical in fading light. That rising passage is under a staircase to a walkway along the top of the wall, leading to a roof terrace—an eye in a storm; a place for studying the stars and sleeping out. The shade of Malaparte, domesticated.

And in quarantine from the rest of the house, projected out over the spur edge away from the earth-bound ‘snake’, is the control space—the master bedroom and its bathroom—sealed off by a geometrically complex door. This is where the dream of this house has to be dreamed. Hanging beyond the ground, this suite seems to counterbalance the whole house. It offers the prospect of the future accumulations of friends and stuff that will fill the space that now seems baggily large.

“The house winds round and looks at itself,” says Kirsten. From the northern window-wall of the living room, you can see feet going up the passage to bed; guests arriving to park at the neck of the spur. You can see the window in the razor-edge prow, behind which children could be lying—half seeing the adults on the terrace or the raking lights of a passing car, or catching the rising sun. A receptacle of dreams to come, to lose. You can look back to the cockpit kitchen. From a room in the ‘snake’ you can see right down the vista cut through the trees to Apollo Bay, hundreds of metres below, kilometres away. The timber-clad, zig-zag facade edges the western forest. Windows are targeted to show tree bases. From here you can also see the barbecue deck. This is the side the fire will come from, when it comes.

And that view of the house from below with the jutting, upward-cut box form and the horizontal slab? An irrelevance. Only the photographer will ever see it. This face of the house is projected over the falling apron of the spur, where no-one will go, and is masked by trees from more distant views. It is a facade to be seen from inside: a series of paintings of the ocean and the sky seen through trees, set within rough-rendered grey flank walls, light bouncing in and up from the tree-grain floors. Here, now, as new. And in four decades.

Houses by architects are in tension between the history of the villa and the specific experience of a site and a client. Here I find a near-perfect balance between the ambitions of architectural form and a rich choreography of family living. The earth-slicing wall declares an attitude to being-in-the-landscape that defies the temporary quality promoted by bush-pavilion architectures. (An attitude alas not respected by the landscape works, which seem set to blur the architect’s concept with a literal spreading of a picnic blanket of grass on the hill.) Perhaps this confidently resolved work signals the arrival of a new Australian hybrid, formed by the dynamic conjunction of a wall-house with a stilt pavilion.

|