Neil Bourne, the lead architect on Hobart’s Bridge of Remembrance, commenced the first stakeholder meeting by asking the question that others had no doubt been quietly contemplating themselves: Why am I here? In doing so, he addressed his status as the only architect in the room, a predicament that he’s often found himself in when working on the many infrastructure projects he has completed over almost three decades at Denton Corker Marshall (DCM). In answering his question, Bourne reminded the room that the legacy of public infrastructure in Australia is born of investment in design quality – that what the bridge looks like is important, as it reflects the care taken in the use of public funds and a respect for the value of the public realm.

Bourne’s opening address set the bar for the task that lay ahead, reminding the clients and stakeholders of their responsibility as custodians of public money to be invested in projects for the public good. The remarks were particularly pertinent to the bridge that they were to deliver because the structure had the additional role of commemorating 100 years since the sacrifice made by Australian service men and women in World War I. As a consequence of this role, the project had a politically unenviable breadth of stakeholders and clients, including representatives from all three tiers of government as well as Legacy, the Returned and Services League (RSL) and community groups. Despite this potential battleground of opinions, positions and agendas, the project proceeded from the initial address to a development application within six weeks, and subsequent meetings of the group generated feedback that positively progressed and refined the final structure.

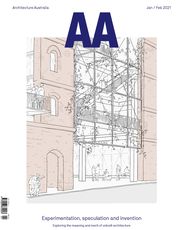

The experience of both pedestrians and drivers is catered for in the refined design.

Image: John Gollings

The mastery of the processes that shaped the built outcome was the result of a combination of strategic collaborations and accumulated infrastructure project experience. DCM partnered with local firms BPSM Architects and Inspiring Place, who simultaneously navigated and crafted the local political and physical landscapes to subtly align the project to its highly contested contexts. The structural complexities of what was essentially an engineering project were integrated into the design processes from the outset. Arup and DCM have collaborated for decades to design and facilitate high-quality civic projects. And, in the Australian way, the public has shown its love for many of these projects by bequeathing them nicknames. Projects like “Jeff’s Shed” (the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre, 1996), as well as the “Cheese Stick” and the “Tube” (Melbourne International Gateway, 1999), generated a repeating suite of techniques and formal devices that has been adopted in the Bridge of Remembrance. The metallic blades meeting with a thin aerofoil edge at just the right point to catch the eye of the passing driver has its origins in both the Bolte Bridge (1999) and Jeff’s Shed. As they twist towards the sky, the blades create a sense of enclosure within a linear plane, like both the Tube and Webb Bridge (2003) in Melbourne’s Docklands precinct. Finally, just like the Cheese Stick, these blades peel back towards the ground to emphasize the experience of movement for the passer-by. The Bridge of Remembrance is a pivotal addition to this lineage of work; it uses the same elements to resolve structural constraints, without conflict, in a way that celebrates the ephemeral moment of a driver and a pedestrian encountering the bridge at different speeds.

One of the aims of the design was to unify a number of disparate elements in Hobart’s memorial precinct.

Image: John Gollings

Despite the risk of acting only as an echo chamber for DCM’s kit of parts, these ideas resonate with the project’s brief and site. The bridge’s aerofoil edge creates a deliberate but not too overt reference to wartime forms, with the riveted cladding twisting in a way that speaks to the memory of military ships and planes. The vertical shift of the aerofoil that marks the entrance point at the north-western end echoes the conifers that line the adjacent Anzac Parade to the south-east. The use of a plane at the entrance, rather than two single posts, heightens the focus on the Cenotaph by screening out both the dominant kunanyi/Mount Wellington looming above and the highway running below. From this height – a move that was necessary to achieve the elevation needed for future road widening – the bridge tilts downward towards the Cenotaph, while the sides fall away to reveal its civic context.

At this point, the framing highlights an unfortunate misalignment of the Cenotaph to the rest of the ensemble on the site – a legacy of earlier, more piecemeal decisions. The Cenotaph was designed in 1925 by local architects Hutchinson and Walker to align with a driver’s dashboard view from Macquarie Street, the civic spine of Hobart flanked by sandstone government buildings. However, a lack of time and money meant that the original landscape design was not delivered at the time. When landscaping was realized in the 1930s and ’40s, only parts of the original scheme were adopted, and the foreground avenue was aligned to the tree-lined drive of the adjacent Soldier’s Memorial Avenue, which is close to, but awkwardly just out of line with, the axis of the Cenotaph.

The plane at the bridge’s entrance screens out peripheral views and heightens the focus on the Cenotaph.

Image: John Gollings

Despite the unresolvable physical misalignment, the bridge masterfully achieves the conceptual and physical link that Ian Terry’s 2001 Cenotaph conservation assessment 1 called for to unify and simultaneously elevate these disparate elements. The subtlety of expression, avoiding overt Anzac references, continues the Cenotaph site’s objective to memorialize the collective rather than individual soldiers or conflicts. This is achieved through a singular expression that shifts to contain a multitude of images when viewed from different positions. The resulting ambiguous form also leaves the bridge open to other meanings, including the commemoration of inevitable future wars.

Historically, a tension exists between the Cenotaph site as a space reserved for a sole purpose – pausing to remember – and an amenity that is an expansive green public space within the heart of the city centre. The very creation of this bridge to invite the community, including cyclists, into the site is a bold and progressive move by the site’s caretakers. But it took the skill of the project team to design a piece of infrastructure that enhances the site’s sacredness and sense of ceremony without allowing them to dominate the everyday experience.

While we await the public’s informal validation of the project in the form of a suitable nickname, it is indisputable that the bridge leaves a multifaceted legacy of its own. It demonstrates the contribution that an infrastructure project can make to the civic landscape via the delivery of a highly refined piece of public architecture. But also, more significantly, DCM and Arup’s gift of experience to the local firms with which they partnered, and to the government clients who will continue to commission other projects across the state, is invaluable. DCM’s view of infrastructure projects – that they are worthy of as much care and attention as the practice’s museum and public office commissions – has fostered a valuable addition to Hobart’s urban realm that will join the honour roll of great Australian public infrastructure projects.

1. Ian Terry, Hobart Cenotaph conservation assessment (Hobart: Hobart City Council, 2001).

Credits

- Project

- Bridge of Remembrance

- Architect

- Denton Corker Marshall

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Neil Bourne (director in charge)

- Consultants

-

Builder

Fulton Hogan (main contractor), Haywards (steel fabrication)

Cost consultant WT Partnership

Landscape architecture and stakeholder engagement Inspiring Place

Local architecture liaison BPSM Architects

Project manager Matrix Management Group

Structural, lighting and civil engineering Arup

- Aboriginal Nation

- Hobart is now known by many Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people as nipaluna.

- Site Details

-

Location

Hobart,

Tas,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2020

Category Landscape / urban

Type Infrastructure

Source

Project

Published online: 4 May 2021

Words:

Alysia Bennett

Images:

John Gollings,

Neil Bourne

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2021