Linda Corkery

Hardcover of the book.

For some years now, as his friends and family will attest, Bruce Mackenzie has been promising to produce a book of his work. Towards the end of 2011 he delivered on that promise. And it’s no wonder that it took some time to produce – it is a big book. To chronicle just a sample of fifty years of dedicated professional practice requires some 370-plus pages. Selected projects from his archives include most of the best-known work. They are projects that influenced the directions of landscape architectural practice and that continue to validate the wisdom of a design approach that is respectful of place in all its dimensions and interpretations.

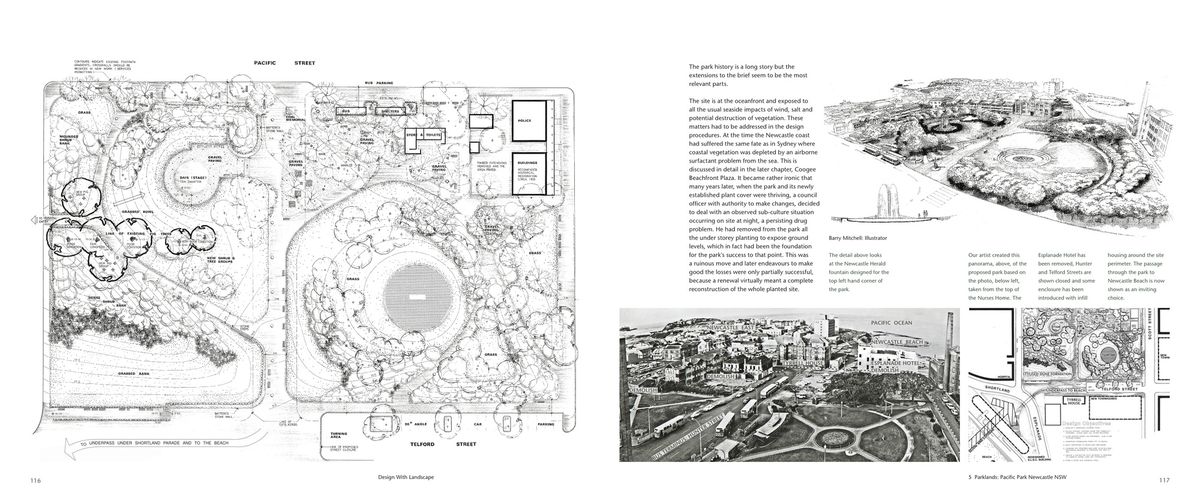

The book is organized into twenty chapters, each generally focusing on a single project or theme, and describing design genesis, process and implementation, often in considerable detail. Many of the projects were “firsts;” for example, the first significant roofscape in Sydney, at the Reader’s Digest building; the first redevelopments of post-industrial harbourfront sites on the Balmain peninsula; the conversion of a twenty-eight-hectare sandfill platform at Botany Bay into a robust revegetated coastal environment, integrating the dune ecology with new recreation facilities. Most of the projects are located in NSW or the ACT, but the list of significant projects not included in the book reminds us that Mackenzie’s professional reach extended into all states and territories, and even overseas.

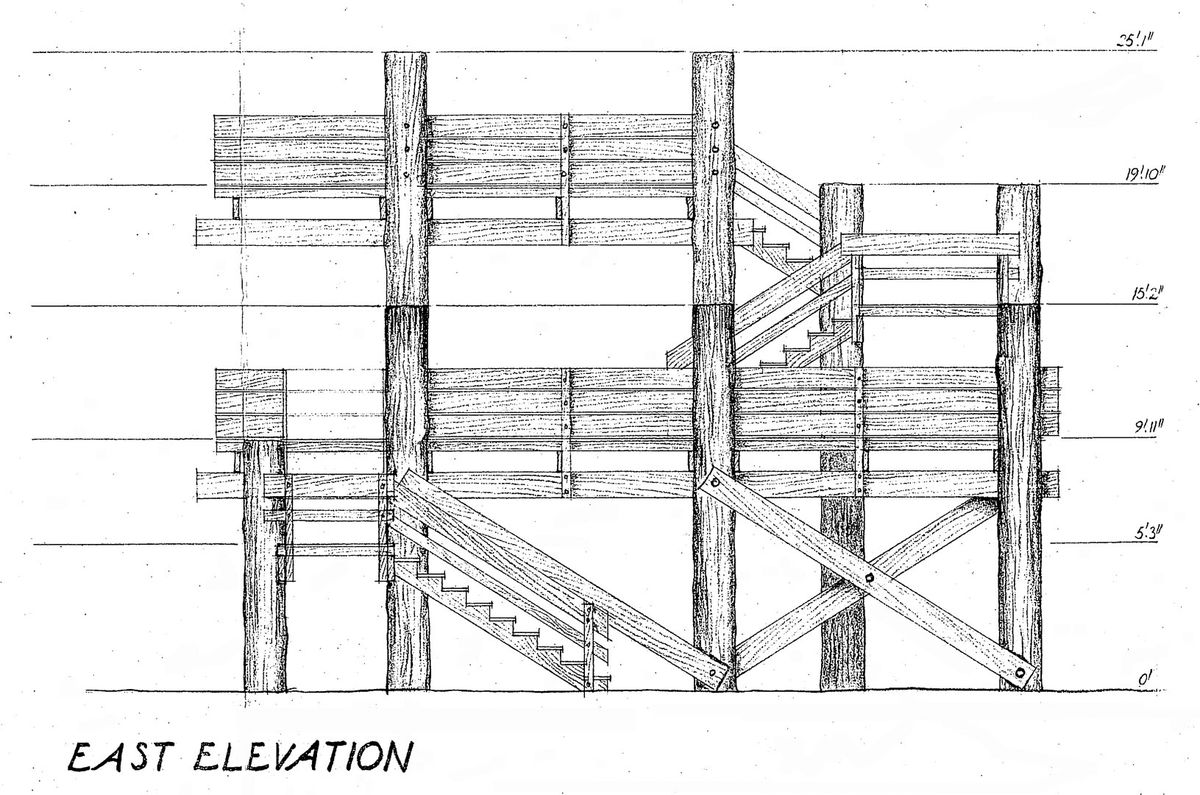

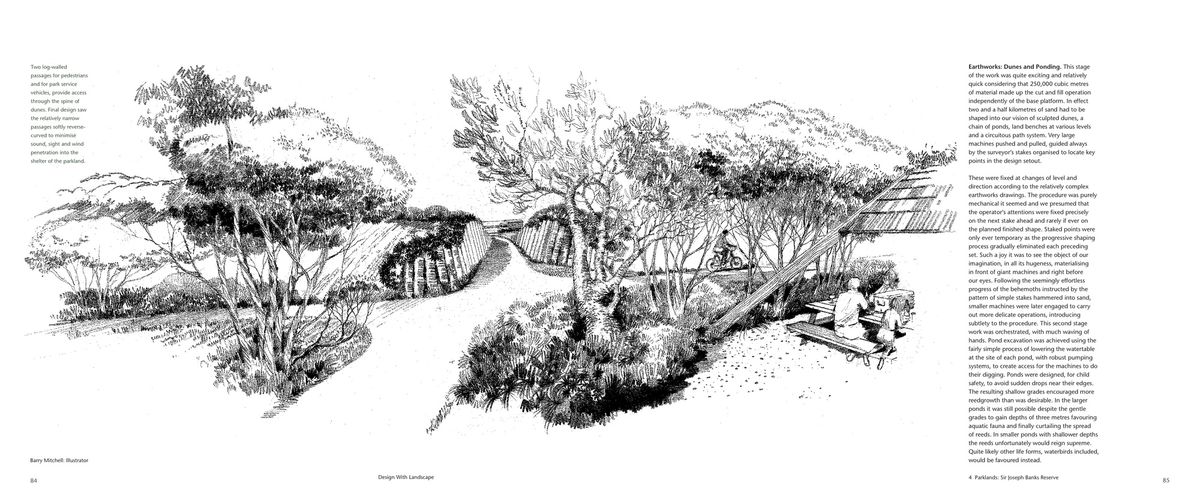

Design With Landscape is abundantly illustrated with more than one thousand photos, drawings and diagrams, including some of the original hand-drawn plans (meticulously reworked electronically by the author), sections and construction details from the office’s work of the 1960s and 1970s. Most of the photos were taken by the author, including some splendid double spreads that span the A4 landscape format.

This book is a valuable contribution to the growing, but still limited, number of publications documenting the evolution of the landscape architecture profession in Australia, and in particular, the emergence of what is now often referred to as the Sydney Bush School. As Mackenzie acknowledges, he was “one of the pioneers of this movement.” His work demonstrates his deep appreciation and knowledge of the Australian landscape and his writings focus on advancing the concept of an Australian landscape design ethos. In the late 1960s and early 1970s this was not yet a widely accepted view, and this approach to landscape architectural practice began to be referred to as the “nuts and berries” style by those more comfortable with a traditional approach to landscape design. But he persevered. In the late 1980s, with the imperative to achieve environmentally sustainable design – “ESD,” later “ecological design,” and now “design for climate change resilience” – Mackenzie’s prescient message and method has become fundamental to built environment design, generally, and to landscape architectural practice in particular.

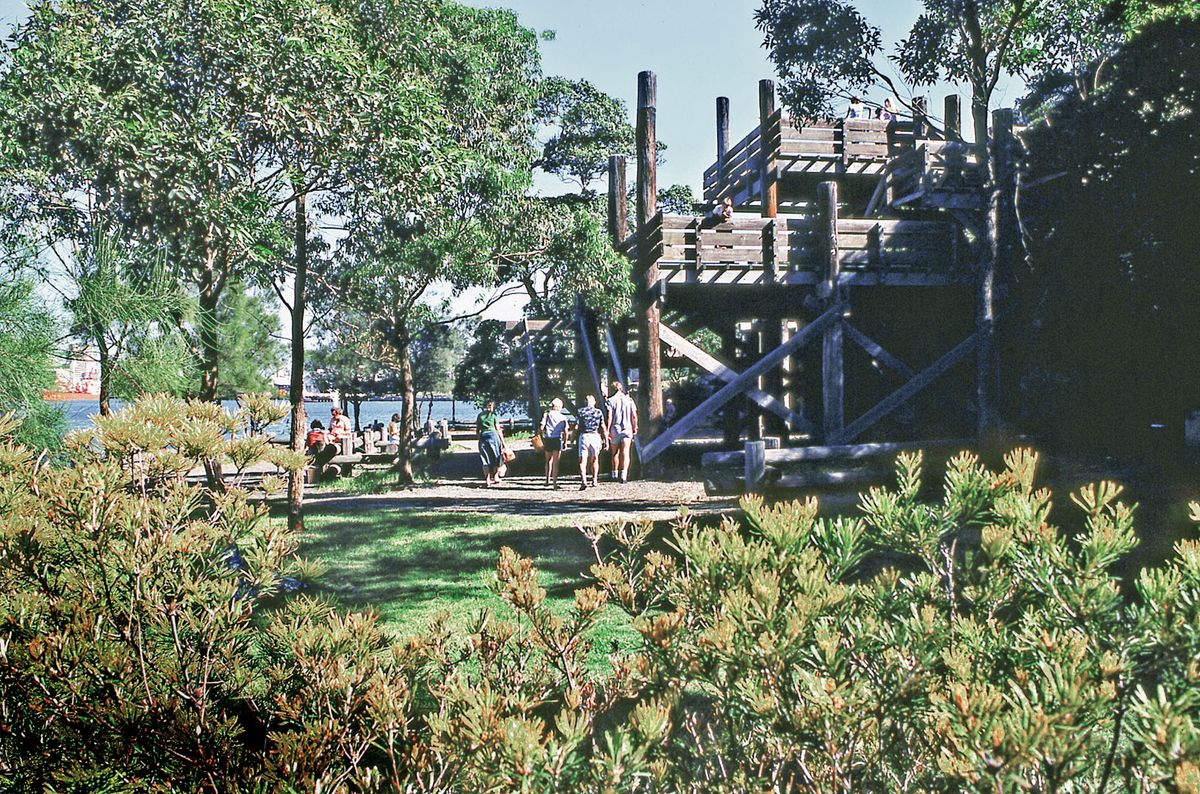

Yurulbin Reserve captures the image of Sydney Harbour and its surroundings. It was developed during the 1970s.

Image: Peter Bennetts

There are multiple perspectives from which this book can be regarded as significant. First and foremost, it presents personal and detailed accounts of the design, construction and afterlife of many major Sydney landscape architectural projects. The most extensively documented project in the book, covering a full forty pages, is Sir Joseph Banks Reserve in Botany Bay. The drawings, photos and text about this project are especially comprehensive. Other works of renown that benefit from this full case study treatment include the harbour-front parks at Illoura and Yurulbin Reserves; the designs for the University of Wollongong and UTS Kuring-gai campuses; Coogee Beachfront Plaza; and Mackenzie’s involvement in the masterplanning for the Millennium Parklands, now Sydney Olympic Park. Curiously, Mackenzie has chosen to include chapters on parking lot designs, one of a number of admirable residential projects, and a brief report of the 1982 environmental battle to preserve the Terania Creek rainforest. These may have been included to illuminate the breadth of issues and opportunities landscape architects deal with, but it is at the cost of not documenting other important projects such as the masterplan for Sydney Park, Duck River Concept Plan, Sydney International Airport and ACT office park projects.

Sydney Olympic Park. As part of the Hassell design team, Mackenzie was responsible for the site – wide planting strategy incorporating the plant species of the local region.

Image: Bob Peters Imaging, courtesy of Hassell

Mackenzie’s text focuses primarily on ecology and “spirit of place” and less on the design process, and there is an emphasis on the making of these projects. He recounts, for example, frustrating exchanges with government agencies and struggles with promoting a landscape-led point of view, especially in relation to the big infrastructure projects. In the progression of project types presented, we can see how the development of Mackenzie’s practice paralleled the evolution of the profession of landscape architecture in Australia. It was also a critical period for the rise of Sydney as a global city and the work Mackenzie undertook was often breaking new ground in major public domain work. In recent years, Bruce Mackenzie Design has been involved in the early phases of project design and Mackenzie is generous in giving a nod to the next generation of practitioners who have, in a number of cases, carried on with design development from the masterplanning phase of work initiated by his practice.

For Australian students of landscape architecture, this book provides a fifty-year overview of the work of an individual and a design practice that instigated a deep understanding and appreciation of, and devotion to, preserving the qualities of the Australian landscape. The text and illustrations – including transects, sections, plan and construction detail drawings – aim to be instructive as well as inspiring. Equally important, these projects have now been in the ground for twenty to thirty years and are available for students to visit, experience, analyze and document. They have matured to become the highly valued urban landscapes and managed urban bushlands of our daily lives, so well integrated into their contexts that many visitors no doubt regard them as “natural” settings.

The final chapter of the book, “Retrospective,” provides an insight into Mackenzie’s personal background – growing up in Sydney during the years of the Great Depression with a single mum, discovering the delights of a “boy’s landscape” of beaches and the great parklands of Sydney’s eastern suburbs. As a young man, he worked on the Daily Mirror/Sunday Truth newspaper, and later as a photo engraver, took art classes and adventured throughout the Australian and New Zealand bush. Mackenzie alludes several times to the “dichotomy between formal and informal paths to practice;” that is, the self-taught, no-university-qualifications path. While not recommending the informal path, he offers a sentiment with which most academics in higher education would concur: “ … while formal education is a valuable and accredited resource, I believe strongly that the ultimate responsibility for learning lies with the individual student and not with the system.”

As he reflects, the combined experiences of early adulthood fuelled a passion within the young Bruce Mackenzie for design and for nature that would reach full force in the decades ahead. The passion found expression in his landscape design work, and in writings and public presentations which provided a platform to promote his views and to challenge others to reconsider their approach to landscape architecture in Australia. In this important compilation, the author’s voice continues to ardently affirm this stance and the project work presented is proof of its effectiveness. In the final summation, Mackenzie’s directive to those who aspire to design with landscape is clearly put: “What is essential is to work with the site, pay great respect to the people who will use it and respond to the local environment. Whatever might be the case, work with passion, and extract from the site its inherent qualities.”

Neil Hobbs

I met Bruce Mackenzie thirty-five years ago, around the time that his reputation for innovation was established. The balance of his fifty-year career has seen great advances for the profession and Bruce is now recognized as a “profession-builder,” someone who sets standards for other landscape architects to follow, breaks down cross-professional barriers and elevates landscape architects to their rightful place in creating our built environment.

The paperbarks (Melaleuca quinquenervia) maturing on their imported sandfill base over the bay, Sir Joseph Banks Reserve, Botany Bay, New South Wales, 1980s.

Image: Bruce Mackenzie

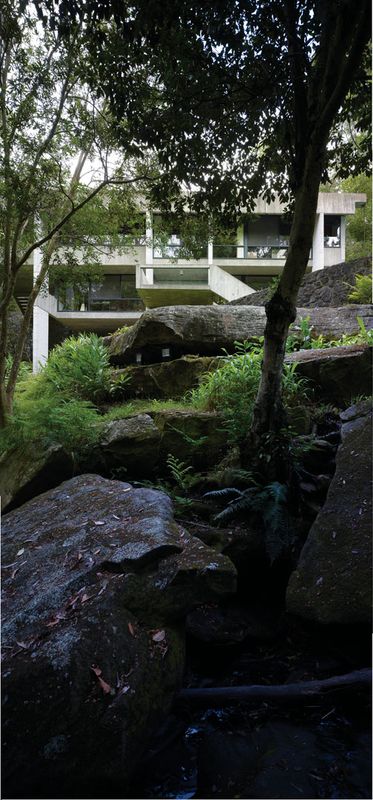

Bruce came from a background of bushwalking and graphic design, meaning his path to landscape architecture was not conventional. He learnt by doing. This may be the secret to the innovation of his design practices and methodology. John McInerney wrote in the forward to Bruce’s book Design With Landscape that “all landscape is local.” Over fifty years Bruce has unerringly responded to the local quality of a site. It is simple enough looking back to see how apt Bruce’s approach to Illoura Reserve and the other Sydney Basin projects were. But Bruce was taking risks. What if the site planning and landscape manipulation at Sir Joseph Banks Reserve failed, or if the Kuring-gai University of Technology Sydney campus destroyed the fragile sandstone-based vegetative cover? Time has shown that these radical approaches are now considered first principles. However, these early works were delivered by a very small practice, with no technical support other than the skills held by the office.

It is worth noting that in the late 1960s specialist sub-consultancies did not exist. The measure of Bruce’s work is that it has promoted the development of these professionals and industry suppliers. Landscape material suppliers were thin on the ground, as were plant nurseries. Not to mention landscape furniture. I remember well the early timber prototypes that Bruce designed and installed in projects during the 1970s, and which were later developed and fabricated by his street furniture company, Town and Park Furniture.

Bruce’s ideas found a receptive ear in the National Capital Development Commission. While this led to fresh approaches to landscape, Bruce readily admits to a failure to break through the dominant road planning culture in Canberra at the time, and laments how this culture still prevails today. In many other instances, in other cities, Bruce’s compelling design arguments and lucid graphics were able to convince a then crusty engineer-based local government system that design with landscape offered an alternative to previously held beliefs.

Bruce was always a collaborator, right back from the days when his office was located at Ridge Street, North Sydney in the 1960s (a building that also housed architects/landscape architects Bruce Rickard and Harry Howard, architect Ian McKay, photographer David Moore, consultant designer Gordon Andrews and graphic designers Harry Williamson and Roger Roberts). A quote from Design With Landscape that needs reinforcing: “There is no room for tolerating boundaries that diminish the value of the aligned professions working together.”

Bruce was a leading figure in the Joint Professions Standing Committee on the Environment and actively campaigned against logging in Terania Creek rainforests in northern New South Wales, demonstrating that a passionately held belief in the conservation of the environment was not just a logical role for a responsible landscape architect, but also a political duty. Bruce’s passion for landscape has driven his career, and I look forward to its next phase.

Laraine Mackenzie

I have been working with Bruce Mackenzie for more than thirty-five years but unlike Marion Mahony Griffin, the wife of American landscape architect Walter Burley Griffin, I can not claim to have influenced a single project. Instead, my skills have freed Bruce from having to be overly involved in office management and administration, which like most designers, he does not enjoy.

In 1976 in our office at 7 Ridge Street in North Sydney, via my IBM golf ball typewriter, I thoroughly enjoyed my role as the secretary. I had been used to working in an architectural office, but this was different. Everyone here was so committed and enthusiastic about their work and I was impressed by the variety and number of jobs that were being worked on at the one time. Specifications, reports etc. were typed on that poor old golf ball typewriter. I also remember the wonderful office lunches where the problems of the world were solved or films and plays were critiqued.

In 1978 we moved to Post Office Street in Pymble and eventually the typewriter was upgraded to a Hewlett Packard “word processor,” which meant that up to three A4 pages could be stored in the memory for correction before printing. We thought it was amazing. Bruce held the position of New South Wales State President of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) from 1980 to 1981, after which he became the national president. There was no secretariat at that stage, and our whole office became very involved with the AILA’s matters, including the 1982 IFLA Congress in Canberra, which involved more than eight hundred delegates. Life was very busy.

In 1983 Bruce and I married. In her electronically published memoir The Magic of America, Marion Mahony Griffin wrote of Walter Burley Griffin: “I was first swept off my feet by my delight in his achievements in my profession … and then with the man himself. It was by no means a case of love at first sight, but it was a madness when it struck.” This seems a bit dramatic, but it was similar.

The office later moved to Sydney Road in Manly. We designed and built our house close by, walked to work and many more young landscape architects joined us over the next decade or so. Life in Manly was wonderful. We got an NEC computer but it was so slow that it was soon replaced by a Mac 11. We have remained completely besotted by the Macintosh system ever since.

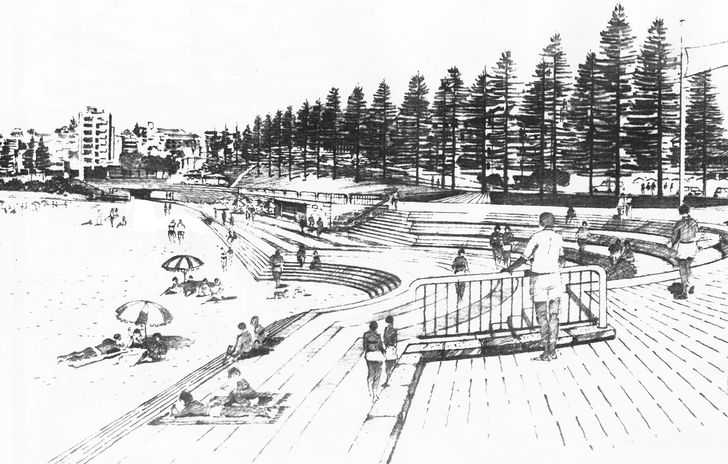

Artist Barry Mitchell’s rendering of the proposed Coogee Beach amphitheatre and the background of the new planned environment, 1980s. The project was completed in 1993.

The daily habit of office lunches continued and, I think, made an enormous contribution to staff morale. During this period we won the Coogee Beachfront Plaza competition, which led to a very good party. The workload became huge and the projects were interesting and challenging.

In about 1992 Bruce started to design the range of street furniture that became known as Town and Park Furniture. This was a big life change as it meant we went to work on top of a factory, with workmen downstairs assembling furniture. No more lunches. Bruce still worked on prominent landscape commissions as a consultant but my major role at this stage was organizing this burgeoning business.

My involvement in the landscape profession, since that day back in 1976 when I somehow became a part of it, has been a great experience. Our landscape friends and colleagues in Australia and all over the world, made mainly because of Bruce’s involvement with the AILA, have enriched our lives enormously.

At the New South Wales Chapter’s recent awards and Christmas party event I was reminded of earlier times, when Bruce Mackenzie and Associates was winning awards and how exciting it was to be involved with people who were so enthusiastic and dedicated to their profession, the community and to the environment.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 21 Jul 2012

Words:

Linda Corkery,

Neil Hobbs,

Laraine Mackenzie

Images:

Bob Peters Imaging, courtesy of Hassell,

Bruce Mackenzie,

David Moore,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2012