Running Dog house addition, Jan Juc. Image: Erica Lauthier

Unwrapped elevation. Image: Erica Lauthier

Different tectonic strategies and surface modelling result in quite distinct characters in each upstairs space. The “candy wrapping” tectonic of the terrace. Image: Erica Lauthier

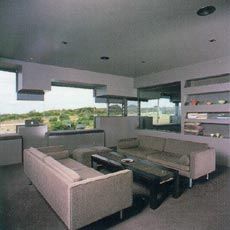

The “carved mass” of the living area, with Loosian overtones. Image: Erica Lauthier

“Skin and bones”. Image: Erica Lauthier

Optical echoes in the “reflection” bathroom. Image: Erica Lauthier

View from the main approach. Image: Erica Lauthier

The entrance to the house, with its complex array of materials and junctions. The long slim shed shelters both house and horse stables. Image: Erica Lauthier

Mary Mount Thoroughbreds house in a horse stable. Image: Erica Lauthier

A long slot affords views from the kitchen to the landscape and stable, and from the bedroom to the foaling box. Image: Erica Lauthier

The chimney, set against a picture window, generated from the dalmation’s spots. Image: Erica Lauthier

The bathroom is separated from the living areas by discreet arrangements of shelved books. Image: Erica Lauthier

Architecture announces itself in many ways. In popular mythology, the myth of architecture’s presence resides in its difference from the established built environment – a fable of innovation triumphing over convention. The two houses under review here, designed by Brearley Middleton, are both familiar and different. Both are also overwhelming architectural in another subtle definition of the term: they display an extraordinary attention to the persistent execution of built form.

In an era when exegesis consistently elaborates the ideas behind a building, a set of references that exist in form and find their meaning in “external” discourses, it is refreshing to discover buildings that can stand alone. Of course the references are there.

Of course no work of architecture is autonomous. It is always enmeshed in codes: building codes, fire codes, architectural history and cultural conventions mapping a certain trajectory of power relations. Nevertheless, it is satisfying to find buildings whose very substance contains the claims one would want to make about them. While more elaborate knowledge of the ideas informing the work, garnered from conversations with the architects, enlarges the conceptual elegance of the buildings and the admirable ambitions of the makers, this prior knowledge is delightfully unnecessary for a tactile and intellectual engagement with the buildings – at least by one who knows something about architecture. I suppose this is always the coda.

Robert Lowell’s famous poem “Mending Wall” evokes the quotidian pleasure of repairing a wall. One of the pleasures of architecture is its capacity to attend to the complexity and ambivalence of a wall’s meaning, place and function. These two houses explore different apprehensions of space as modelled by wall surface. What follows is not a description of the projects but an engagement with their respective acts of building a wall.

For those seeking definitions of “Architecture”, Brearley Middleton’s Jan Juc House presents a familiar tale. After a first sweep through the building, one is struck by the contrast between the familiar spaces and detailing of an off-the-rack builder’s design on ground floor level, and the obviously architecturally designed volumes and surfaces above. From a certain viewpoint in the downstairs dining room the pilaster profiles in the entry and loungeroom align with the profile marking the edge of the staircase. Someone has been here and noticed this architectural detail. It has been replicated. Someone has been looking carefully. Architecture focuses our attention.

A study in contrast and surprise, the house presents the external dichotomy of solid concrete ground floor and a timber skin first storey; cut away at terrace level to declare its frame-as-skin function. The reversal of expectation and a further level of surprise occurs upstairs in a suite of spaces notable for each room’s distinct character. This differentiation is not simplistic nor melodramatic, but is achieved through attention to detail, texture, materiality and modelling of space, evincing depth and complexity. An architect has been here.

This exploitation of surprise within the constancy of the domestic interior is a technique associated with the work of the Viennese architect Adolph Loos, but it was also developed to perfection in certain late eighteenth century houses through the circuit plan – a kind of picturesque tour of the domestic interior. A room’s difference from another endows the living process with a particular formality, a surprising gesture amongst the apparent informality of contemporary living. It is also a mirror trick, doubling space by sharpening the appearance of variety. This optical illusion is perfected in the upstairs powder room. Here a mirror reflection sends the viewer into an infinite space.

The space she inhabits is transformed in the curved and receding space in the mirror plane. She sees herself replicated over and over again. She exists in more than one space, both before the wall and inscribed into its surface. Space has an optical echo.

Each room becomes an architectural registration of the interior’s distinct activities.

Difference is not accentuated by the separating function of doors and walls (as formulated in the eighteenth century interior), rather partial views give tantalising glimpses of what is to come. But the openings frame only fragments.

Ordinarily, the afterlife of a room lies in its occupation, in furnishings and colour schemes. But in these rooms, the afterlife – or inhabitation – occurs through architecture. It is achieved through the consistent treatment of wall, floor and ceiling planes, and through the work of built-in furniture and appliances.

There is here another relationship to Loos’s work. Loos’s ability to model internal space through volume has been frequently noted, but what happens to the received properties of architectural elements under Loos’s transforming eye is less often discussed. However, mirrors and windows doubling the ambiguity of the walls have drawn recent critical attention. Walls conventionally divide and maintain the separateness of each room, but, in the Loosian interior, walls often model space through their double function as a stair or cupboard. Cupboard as wall, wall as modeller of volume, wall as frame to establish control and symmetry of the view are all exploited in the upstairs loungeroom at Jan Juc.

When visiting, I wondered how accurately the play of surface modelling volume would photograph in this upstairs room, pierced by external light reflected off sea, clouds and the open landscape of the coast. The process of comprehension, of trying to put it all together when you are there, the accretion of parts to form the sense of the whole, is a gradual apprehension, formed by moving around and inhabiting the spaces over time. Yes, it is all here, you think, as you walk away from the house. Light saturates space, enabling us to read volume, material, texture, detail. But, when inscribed on a photographic surface, light can also obliterate the very conditions of visibility it enables. The transmission of light from one medium to another can result in exaggerated contrast. Light’s bleaching glare may saturate the picture plane, obscuring tone, details and minute particulars. The subtlety of space modelled by surface may be hidden by the surface of the photographic print – a warning to readers of this review.

Externally, the themes of reversal, and of wall, continue in Sinatra Murphy’s extremely successful landscaping. Indigenous grasses are planted at regular intervals in long diagonal lines crossing the front of the block. Between the rows, crushed shells crunch underfoot. The straight line, the footprint of the wall, is etched into the earth.

Elements of an indigenous landscape are corralled by a regular agricultural pattern.

The observer confronts the strange beauty and power implicit in this imposition, an inescapable allegory for this country.

The Mary Mount Thoroughbreds house and horse stable (Kyneton) explores a different sense of the wall’s intricate functions in the drama of reversed expectations.

From the approaching road the first thing one notices is the scale and proportions of a very long wall/shed, stretching some forty-odd metres and clad in a familiar corrugated iron. At the front entrance one encounters a parodic assemblage of humble domestic materials – fake brick cladding covers the garage door, and is unceremoniously included in the front wall and an entrance lobby backed by aqua corrugated plastic.

The ordinary, slightly makeshift materials, the proportions and the detailing, and the strange tilt of the skillion, confirms that knowing hands are at work. The growing apprehension that all is not as it seems is confirmed as the wall starts to move off to its south-west point; a slot window, a picture window, the meeting of glass and chimney brick instigate a multitude of materials and junctions.

The south elevation treats the wall plane as shallow relief, exploiting the layering of a wall plane through recessive and projective surfaces, some real, some optical. It revels in the detail of one plane, no matter how small, meeting another. These moments might be more receptive to photographic representation. A flat wall is more successfully represented on the surface of a photographic plane, but, unless taken from an angle, the work of the perpendicular junctions to delineate meeting points and model space may escape the photographic view.

The whole house can be viewed as a set of planes, graded in sequence as they develop from the semi-transparent brick, glass and timber plane on the south elevation to an almost opaque corrugated iron of the north elevation. The architects describe their exterior surface treatment as collage, but the technique of treating the wall plane as a shallow relief has been around for centuries. Perhaps the difference lies in the use of more abstract forms, together with fenestration. Gothic and Renaissance builders manipulating the shallow space of the wall plane did so within a Classic or Gothic system. Both sharpened their tools on the ambiguity arising from the distinctions between structure and applied structure as wall decoration.

Differences in the centuries-old technique also arises from the materials available.

Stone could be carved, incised, or one set of stone ornaments overlaid on another. New technologies of lighter materials now allow the external wall to be palpably treated as a thin skin. Collage relies on the persistent build-up and overlap of thin materials to build surface through accretion, so it makes some sense to use this label. However, Modernist collage is not usually organised around a linear narrative, as is perhaps implied in the south-east elevation as one moves along a progression of materials from weatherboard to concrete sheet, to tile pattern and doorway – where the facade breaks into an overlapping glass, timber and painted timber thicket. The progression demonstrates the paradox known to Renaissance and Modernist architects: a wall divides and encloses its adjacent spaces, but this division is replicated in the layers that stabilise and divide the wall plane itself.

While taking account of the superb landscape views from the house, the interior itself, like those of Adolph Loos, also organises the drama of surprising internal views.

From the kitchen and bedroom windows that peer out onto the stables, to the glass wall dividing the study from the bathroom – where one’s nakedness is clothed only by the discrete arrangements of shelved books – the house inscribes unusual interior views through framing wall planes. A house is a set of adjacent activities grasped at architectural meeting points. A whole is articulated by the junction of particular parts.

The execution of an idea at more than one level – that is, in plan, and in internal and external elevations – has a powerful cumulative effect. This layering of intention and attention is persuasive to witness.

Both Jan Juk and Mary Mount explore the territory of architecture: how does building make space? In this process a multitude of decisions arise. The wall is one of the principal devices through which architecture articulates such decisions. Both houses explore the persistent ambiguity of the wall plane, an ambiguity nominally suppressed by buildings in order to make the act of enclosure legible or simple. A wall, as these architects so effortlessly demonstrate, may be many things. Is a wall a shallow relief plane, a junction between spaces, or a passage? Does it model internal volume or is it an element of dual material functions: both wall and cupboard, or window and wall? Building a wall, the simplest of acts, discloses its material and intellectual complexity. Visiting these two houses we enjoy a realm of architecture where such intricacies are never suspended but continually hover and double back on themselves.

Architect’s Statement

Running Dog House Addition, Jan Juc

Two lawyers commuting to Geelong from the ocean edge of Jan Juc. One a classicist the other a romantic. Two ways of seeing: one controlled, the other free. A hybrid solution merged these ideologies and allowed the two to coexist. The external form is punctured by square view-framing windows and then split in two by a continuous ribbon window. The result in a simple skillion box with a running dog window.

Four programs = four tectonics:

eating = skin + frame (natural/impermanent/body as frail container)

lounging/sleeping = carved-out solid (monotone/permanent/dark)

cleansing = tectonic of reflection? (white on white/infinity mirrors/spatial ambiguities)

cooking = planar (artificial/colour saturated/machine modernity)

Each tectonic has a degree of irony. The carved space is left hovering by the ring-barking of the running dog. The planar has ordinary builders window framing. The skeletal space has frames which stop short of supporting walls. Difference is exacerbated by the removal of thresholds between the tectonic spaces. Artist Gordon Matta-Clark’s building cuttings have inspired the spatial ambiguity of the openings between programs. His projects, Datum and Intraform, are re-appropriated: where cuttings suggest mirror images we have used actual mirrors; where they reveal surface shifts we reveal program shifts….. Sinatra Murphy’s landscape is a rich intervention amongst its lawn neighbours. It heightens both the artificial nature of the suburb and the wild character of the native foreshore.

James Brearley.

Architect’s Statement

Mary Mount, House in a Horse Stable

Ian thought our proposal was “simply crazy – I don’t want those architects”. Cynthia refused conjugal relations until “those architects” were hired. He enthused when our concept proved to halve the costs of his previous concepts. The brief proposed a number of independent buildings including stables, sheds, office, house and guest accommodation.

Our strategy was to place all of these programs under one roof. Opening views and access between programs created an architecture of super-adjacency and a culture of congestion (Koolhaas): bedroom + foaling box; office + horse wash down; kitchen + horse crush; shower + library; high-art + tractors; shower + library; guest accommodation + stables breezeway; pool + horse paddock; verandah + holding yard. The project has been built in three stages over three years. The congestion of ideas, styles and programs creates a freedom which has influenced behaviour. Prior to the final stage the client re-appropriated horse quarters as living spaces and “ballroom”. Invention, intervention, improvisation and understanding between client, architect, builder and site results in a rich collage of affordable materials, humour, activities and layered views. The clients describe the building as “a place where a mere eye scan makes one think that you are at the races, with your dogs, in an art gallery or in a beautiful country setting all at once!! Standing in the kitchen and seeing horse trainers mounted in the stables takes our breath away.”

James Brearley and Luke Middleton.

Credits

- Project

- Running Dog House addition, Ocean Boulevard, Jan Juc

- Architect

-

Brearley Middleton

- Project Team

- James Brearley, Kirsty Fletcher, Bruno Imeneo, Luke Middleton

- Consultants

-

Builder

Derbys Builders

Landscape architect Sinatra Murphy

- Site Details

-

Location

Jan Juc,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

- Client

-

Client name

Judy and Michael Meagher

Credits

- Project

- Mary Mount Thoroughbreds, house in a horse stable, Kyneton

- Architect

-

Brearley Middleton

- Project Team

- James Brearley, Kirsty Fletcher, Bruno Imeneo, Luke Middleton

- Consultants

-

Builder

Alan Bell, Kyneton (house), Equine Builders (stables)

Structural consultant Peter Felicetti

- Site Details

-

Location

Kyneton,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

- Client

-

Client name

Cynthia and Ian Goudie