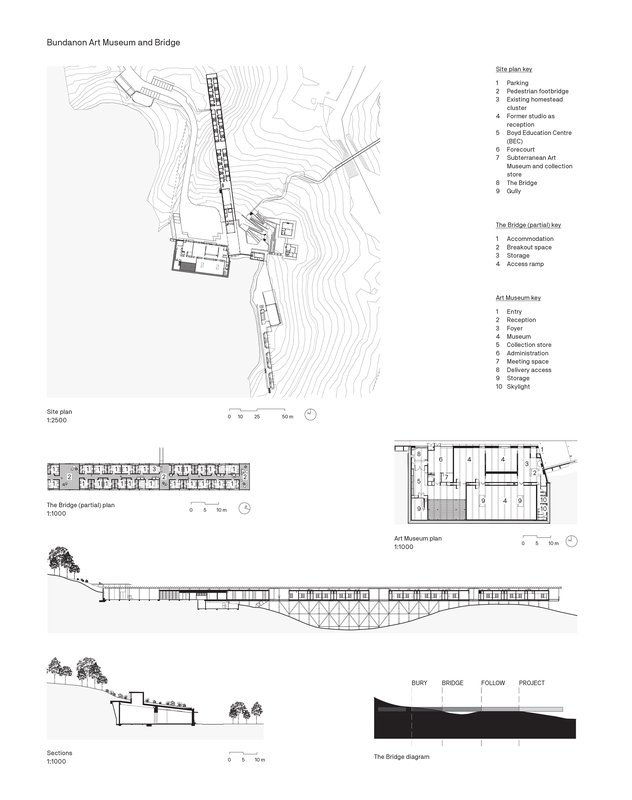

Near Nowra in the Shoalhaven River valley of southern New South Wales, two properties – Riversdale and the adjoining Bundanon – were the home of artists Arthur and Yvonne Boyd. In 1993, the Boyds donated both sites, including their substantial art collection, to the Australian government and the Bundanon Trust was established. The Boyd Education Centre (BEC) – the winner of the Australian Institute of Architects’ Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Buildings in 1999, designed by Murcutt, Lewin and Lark – is on the Riversdale site and was constructed to facilitate artist-in-residence programs.

In 2016, the Trust released a masterplan prepared by Tonkin Zulaikha Greer and announced a $28.5 million expansion plan for the whole property. The announcement was greeted with a terse open letter from a number of prominent Australian architects (Brit Andresen, Richard Leplastrier, Peter Stutchbury and Lindsay Johnston) questioning the respect shown by the masterplan for the wishes of the Boyds and the vision of the BEC architects.

From a distance, The Bridge – at once bold, elegant and pragmatic – appears to recede into the bushland behind.

Image: Rory Gardiner

The announcement progressed to an invited competition, which was endorsed by both the Australian Institute of Architects and the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects. The selected entrants, who were invited to “partner with the Trust rather than work in the isolation of a conventional competition,” were obliged to participate in a site orientation “to familiarise themselves with the Site and to contextualise the Trust’s objectives.” 1 Deborah Ely – until recently, CEO of the Bundanon Trust – believed that this site orientation was a critical part of the entrants’ briefing. She did not want the architects telling the Trust what it needed; she wanted them to understand what was needed.

The winner was selected on the basis of a refreshingly modest submission requirement followed by a jury interview. A team led by Kerstin Thompson Architects (KTA) with Wraight and Associates, Craig Burton, Atelier Ten and Irwin Consult (later WSP) was successful. This was an exemplary procurement process that many other government organizations could (and should) replicate. Its aim was to select the right architects (and it targeted only Australian architects), rather than to determine an outcome.

Along The Bridge, bedrooms open onto an open-air internal street with breezeways carefully spaced.

Image: Rory Gardiner

Part of the concern expressed at the time of the 2016 masterplan regarded the size of the expansion. But with the gifted Boyd collection of more than 3,600 artworks languishing out of sight within shipping containers, the requisite for a suitable, publicly owned venue to display these important works was clear. The January 2020 bushfires, which came within a kilometre of Riversdale, reinforced the need to get these precious items into secure, climate-controlled storage. The Trust also maintained that the expansion was necessary to make the centre viable. The lack of accommodation, exhibition/storage space and food and beverage facilities severely limited how the centre could operate.

Although the site is 1,100 hectares, between the dual threats of bushfire and flood, and the need to conserve threatened species, surprisingly little of the land was available for building. Notions of curated pieces of crafted architecture scattered artistically across the site quickly gave way to what is ultimately a very pragmatic solution. Even so, the Rural Fire Service has deemed parts of the development as prone to ember attack (BAL-29) or direct exposure to flames (BAL-FZ).

The new Art Museum has been partially buried in the hillside, not only for fireproofing but also to avoid overwhelming the site with its bulk.

Image: Rory Gardiner

The adopted masterplan is elegant in form and highly respectful of the context and site; yet it is still a bold proposition. A 160-metre-long trestle bridge – coined “The Bridge” – spans a gully in a confident and strident, though not belligerent, way. Kerstin Thompson describes it as a piece of infrastructure that allows the natural overland flow to operate unencumbered. When presenting the scheme, she shows a simple diagram that captures its essence and how it responds to the environment. From a distance, The Bridge is surprisingly recessive, its dark colours blending with shadow and the dark green of the bush behind. The new Art Museum does not come into view until you reach the arrival forecourt.

A number of critical decisions that depart from the approved masterplan are key to the success of the project: moving the access road and car parking away from the buildings; making all new buildings conform to the level shared by the BEC and Boyd’s studio (existing); and consolidating the new build into a tight cluster.

For most, arrival to the site is via the surface carparks, over a pedestrian trestle bridge (affectionately named “Mini-Me” by Thompson) that traverses the lower stream gully. A service road bridges the gully further to the north, but it has been rerouted around the edge of the clearing, arriving at the rear of the buildings.

Visitors arrive at the site via a trestle bridge that spans the gully between the carpark and the buildings.

Image: Rory Gardiner

A gentle, winding gravel path leads through the remnant domestic Boyd plantings that cluster around the three existing timber cottages (one of which is Boyd’s studio, built in 1981). To the right, The Bridge is fully revealed, delivering a sense of both drama and containment. A zig-zagging accessible ramp completes the journey, linking the lower two timber cottages with Boyd’s studio and the arrival forecourt. The BEC is not visible until you reach the studio. Published photos of the BEC tend to show the building sitting romantically and monumentally alone in the landscape. As beautiful as these photos are, they do not explain the built context of the site.

The path to the BEC is one of discovery, with the approach concealing and then revealing the building through the verandah-ed path at the side of Boyd’s studio; this gives the building a self-contained quality. The KTA scheme understood the importance of maintaining this context and the studio, which some suggested could be demolished. While the masterplan indicates the clear dialogue between the buildings and the shared arrival levels, the new building does not directly compete with the BEC.

The deep-profiled roof of The Bridge extends over the forecourt, creating a social knuckle where all activities converge. Directly ahead is the concrete bunker of the new Art Museum, which also houses staff and the collection storage. Pushed into a reinstated hillside, it is mostly concealed. Mainstream media reports on the expansion have focused on the importance of this building as an “underground fireproof” facility. While this is true, fireproof buildings do not have to be underground. Rather, cloaking the gallery space in the hillside reduces its apparent bulk, which could easily have overwhelmed the built scale of the site, given the building’s spatial and volumetric requirements.

The Bridge extends for 160 metres and has tripled the accommodation available on the site, without interrupting the natural overland flow.

Image: Rory Gardiner

The Bridge finishes with a balcony that projects towards a view of “Arthur’s Hill.” At the southern end of the structure, addressing the forecourt, is the cafe, which leads into commercial cooking facilities and a function space. From there, the new accommodation (the number of beds has been tripled by the development) extends out along The Bridge as a series of timber-clad structures sitting free of the parasol roof above.

KTA has used the idea of en plein air (painting outdoors), of which Boyd was a proponent, to explore how architecture can provide immersion in the landscape rather than a fully mediated environment from which to view the outdoors. Winter heating is provided, but summer cooling is through cross-ventilation and ceiling fans. (Airconditioning is limited to critical areas such as the climate-controlled gallery and high-population meeting rooms.) Along The Bridge, the bedrooms open onto an open-air internal street, with generous breezeways spaced to avoid the relentless gun barrel that a 100-metre-long corridor could become.

Like most KTA projects, the finished building is raw, with a limited palette of materials expressed as honestly as possible. The work is not austere or minimalist; there are many moments of warmth and texture combined with craft-like detailing that lend a sensual quality. Even in the Art Museum, the predominant palette of off-form grey precast concrete and exposed services is softened with extensive use of blackbutt lining and joinery.

The design aims to provide immersion in the landscape, rather than views from within a fully mediated environment.

Image: Rory Gardiner

The deep profile of the roof sets a memorable silhouette datum for The Bridge, sliding over outdoor spaces, indoor spaces and the forecourt. Stainless steel mesh maintains safety in the open breezeways without the need for balustrades. The board-and-batten cladding has a wedge-shaped profile produced through radial sawing, a technique that reduces wastage and allows the recovery of usable timber from much smaller logs. It also happens to replicate the profile of the metal wall cladding. Blackbutt, in solid and ply form, is used everywhere, as wall and ceiling cladding, flooring and joinery. It is barely finished, with a transparent seal.

The materials exhibit an attention to detail that constantly connects you to the outdoors or allows you to temper the environment. Within each tight little bathroom, a window frames a view to the sky. Sliding perforated metal screens control sun, privacy and mozzies as well as potential embers. Tilting panels over the doors allow cross-ventilation.

It is easy to think of this site as a confluence between a natural and a cultural landscape, where the natural has been creeping up and retaking land that was once cleared for agriculture. However, books such as The Biggest Estate on Earth by Bill Gammage2 have taught us that all of Australia is a cultural landscape, and that a healthy landscape requires a balance between natural systems and human intervention. This curated piece of utopia captures many cultural layers particularly well. The new works are not a picturesque response to satisfy our need for beauty; rather, they are a performatively ecological response, displaying an understanding of the natural hydrological systems, flood events and ever-present risk of bushfire. Their beauty comes out of a simple and honest pragmatism and the fulfilment of a brief.

Some time is now required for the landscape to settle and grow after the disruptive intervention of significant building works. In a year or two, the site should start to look its best. A tension remains in parts of the architectural community regarding the appropriateness of the expansion, but I hope that all critics will take the time to visit the new works before passing judgement.

1. Riversdale Architectural Design Competition – Brief and Conditions, prepared by JBA Urban on behalf of the Bundanon Trust, July 2016.

2. Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2011).

Credits

- Project

- Bundanon Art Museum and Bridge

- Architect

- Kerstin Thompson Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Kerstin Thompson, Kelley Mackay, Lloyd McCathie, Michael Archibald, Claire Humphreys, Tobias Pond, Kelsey Jovanou, Henry Russell, Audrey Shaw, Margot Watson, Darcy Dunn, Thomas Huntingford, Tamsin O’Reilly, Christopher Kelly, Nigel James, Sam Ellis

- Consultants

-

Aboriginal cultural heritage

Sue Feary

Access consultant Inclusive Places

Acoustic consultant Renzo Tonin & Associates

BCA consultant Steve Watson & Partners

Builder Adco Constructions

Bushfire assessor Advanced Bushfire Performance Solutions

ESD consultant Atelier Ten

Fire engineer Innova Services

Flood analyst PSM

Flora and fauna consultant Gaia Research

Food services Universal Foodservice Designs

Geotechnical engineer JK Geotechnics

Hydraulic and fire services engineer Warren Smith Consulting Engineers

Hydrologist Woodlots and Wetlands

Kitchen consultant Universal Foodservice Designs

Landscape architect Wraight and Associates with Craig Burton

Lighting consultant Steensen Varming

Planning consultant Locale Consulting

Project manager Capital Project Control

Quantity surveyor WT Partnership

Services engineer Steensen Varming

Signage and wayfinding consultant Maat Studio

Soil contamination EIS

Structural and civil engineer Irwinconsult

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Wodi Wodi and the Yuin peoples

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Type Alts and adds, Museums

Source

Project

Published online: 7 Jun 2022

Words:

Andrew Nimmo

Images:

Rory Gardiner,

Supplied

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2022