Between 1958 and 1975 a boom in the tertiary education sector in Australia saw the establishment of ten new universities – Monash (1958), Macquarie (1964), Latrobe (1964), Newcastle (1965), Flinders (1966), James Cook (1970), Griffith (1971), Murdoch (1973), Deakin (1974) and Wollongong (1975). This more than doubled the number of universities in Australia and mirrored the significant international growth witnessed by these institutions in the wake of World War II. In Australia the policy framework for this expansion was set out in the Murray (1958) and Martin (1964) Reports, both commissioned by then-Prime Minister Robert Menzies, which together comprise the first concerted effort to declare a national vision for tertiary education.

Most of the new universities were established ex nihilo, as new campuses on greenfield or bushland sites, and presented an opportunity to redefine the campus as a site of civic life. The resulting interrogation of the campus as a modern type was motivated by the postwar welfare state agenda for social reform, civic expression and efficient modern life, and has not been repeated on the same scale since.

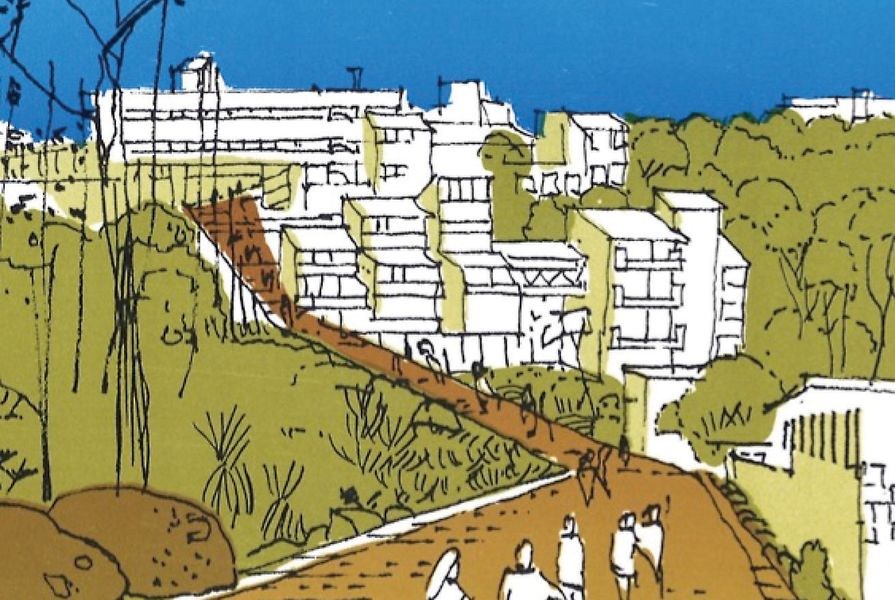

Conceptual sketch of Griffith University from a site planning report in April 1973 by Roger Johnson.

Image: Courtesy of Griffith University

Despite their exurban locations the new universities were conceived as fragments of a complex and dense urban condition that was anticipated to become pervasive after the war. They became sites on which to enact and test contemporary town planning theory, and catalysts for the development of theories accounting for the demand for ongoing growth and rapid change that was seen to be inherent in a range of modern building and urban types, including airports and hospitals.

Planning for growth and change was a ubiquitous concern of the new universities: accommodating larger and increasingly diverse student populations, testing new educational models, recalibrating disciplinary priorities and exploring the changing role of technology were all seen as contemporary challenges. The impact of these preoccupations on campus building designs and masterplans, and on planning as a perpetual activity of the university, deserves further attention.

Among the new universities built in Australia in this period, the Nathan campus of Griffith University is an example where the evolution of its masterplan provides a clear illustration of how the influence of international planning theory and the challenge to design for change encountered regional attitudes towards modern architecture and landscape design.

Griffith was first planned as a college of the University of Queensland for a bushland site adjacent to Toohey Forest, approximately ten kilometres south-west of Brisbane’s CBD. The initial site planning moves – to situate the campus on a knoll that gave way to the north towards a natural creek bed, and establish a ring road that would separate vehicles from a series of pedestrian precincts – were determined in a masterplan prepared by James Birrell in 1966 in his capacity as UQ’s University Architect.

His plan emphasized the natural beauty of the site and was influenced by botanical and geological surveys that identified unique flora species and rock formations. It proposed a series of low-rise buildings arranged around open courtyards and the use of sympathetic materials such as dark brick and exposed concrete to be in harmony with the landscape.

Conceptual sketch of Griffith University from a site planning report in April 1973 by Roger Johnson.

Image: Courtesy of Griffith University

In 1971 Griffith was formally established by an Act of State Parliament and took over its own planning as an independent institution. The Griffith Interim Committee appointed Geoffrey Harrison, architect of Flinders University, to prepare a report advising a suitable direction for the campus masterplan in light of recent international developments that emphasized flexibility.

Under the direction of its founding Vice-Chancellor Peter Karmel, the planning of Flinders had taken Sussex University as a model. Established in the 1960s as one of Britain’s seven new plate glass universities, Sussex pursued an organizational structure based on interdisciplinary schools as an innovative alternative to the old-fashioned college system. Griffith likewise adopted a schools model and Harrison’s report identified a synergy between the dual ambitions for density and flexibility in architecture, and interdisciplinary exchange in teaching.

Harrison advised Griffith to move away from Birrell’s open courtyard plan towards a linear framework that exploited possibilities for modular planning and construction. It reflected an international shift in the campus planning discourse towards the establishment of grid plans and indeterminate building strategies, but at Griffith it was motivated as much by the strictures of the three-year funding cycle of the Australian Universities Commission as by the preoccupation to design for change.

With the first intake of students anticipated for 1975, the Griffith Interim Committee appointed Roger Johnson to prepare a masterplan in 1972. His Development Plan was based on a compact arrangement of buildings along a primary circulation spine with a series of lateral branches that set out a matrix of building envelopes and bush courtyards. Johnson’s justification of the spine advocated by Harrison extended beyond its utility as a model for growth to emphasize its potential as a street that would give a strong image to the campus.

A distinctive aspect of Johnson’s plan was its ambition to integrate the bush setting as a prominent part of the campus image through strong material contrasts and close-range juxtapositions, an approach that was unique among the Australian new campuses. Where Birrell had described a harmonious relationship between buildings and their setting, Johnson wanted (as he later wrote in Landscape Australia ) to create an “antithesis to suburbia,” accentuating the contrast between buildings and landscape “with little or no moderation of one towards the other.” The proposed palette of materials for the campus – evident in its first buildings of a tempered modernist style by Robin Gibson, Blair Wilson, John Dalton, John Andrews and John Simpson – was dominated by off-white-coloured concrete blocks, off-form concrete and metal roof sheeting. The effect was an obvious visual distinction between the constructed objects of the campus and its flora.

The campus plan matrix thus served a dual purpose: to establish a formal logic for future expansion and to create a built register against which the specific topographic, botanical and geological qualities of the bush site could be highlighted. In 1978 Griffith was awarded a citation for Civic Design by the Queensland Chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects and in 1986 received a Letter of Commendation from the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects.

The new universities did not experience the kind of rapid large-scale growth that was anticipated in the 1960s. Their isolation from inner-urban development meant that in many cases they have remained relatively intact as planned environments born of this moment of re-envisioning the modern university. Their strong first-generation buildings have provided a robust ground for subsequent phases of development, a late-modernist counterpoint to the iconic, brand-focused buildings now in favour.

Recent debate on the future of higher education has the potential to change the idea of the campus in a way not seen since the 1960s. The concepts of civic life and modernity that were at the heart of this period of change are once again subject to debate. Insight into the Australian campuses of the 1960s and 70s gives an important historical perspective to this significant national discussion. Rather than emphasize their legacy as artefacts of a utopian vision that did not come to pass, these campuses – and certainly in the case of Griffith – should be appreciated for their material accumulation of thinking around the shifting interface of architecture, planning and landscape and their collective ambitions as civic design.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 1 Sep 2015

Words:

Jared Bird,

Susan Holden

Images:

Courtesy of Griffith University

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2015