Review Naomi Stead

Photography Eric Sierins

Stainless steel, glass and astroturf conceal new ablutions facilities at the rear of the pavilion.

The refurbished pavilion seen across the oval. The original structure had developed a pronounced lean – a condition embraced by the architects.

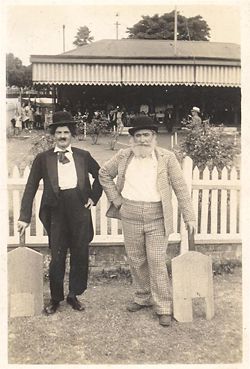

Archival image from the City of Sydney collection, showing a “dress up” at the pavilion during the 1950s.

A new steel verandah stands forward from the original timber columns at the front of the pavilion.

Panes of translucent glass between the stainless steel panels fill the bathrooms with natural light.

Change room within the refurbished structure.

Lacoste and Stevenson has added to and refurbished the Jubilee Oval Pavilion at Sydney’s Blackwattle Bay Park, near Glebe. This is a small, modest project, but it nevertheless tries out several architectural ideas, in a charmingly light-hearted manner. The architects call the project “camouflage”, and it is indeed self-effacing. The addition is not visible from the oval side at all, and from the rear approach it effectively disguises itself by mirroring the grassy hillside at its back, the facade being dematerialized with a broken surface of stainless steel and glass, and the whole topped off with an astroturf roof.

It was always a jaunty little building, half weatherboard grandstand and half blind brick change room, like a kind of thickened verandah, with a striped awning at the front and a flagpole sticking up from the middle of the roof. The pavilion was not heritage-listed, so theoretically the architects could have knocked it down and started again. But the client – the City of Sydney – was keen to retain the building, so Lacoste and Stevenson worked to restore and add to it. They replaced the falling-down skillion roof at the front with a new steel structure standing off from the existing turned-timber column structure. They also added new ablutions facilities in a low strip at the building’s rear. Now, spruced up with a shiny new backpack, the building is more jaunty than ever, in an op art kind of way.

The architects’ requirement was that the back facade should “disappear, ventilate, provide good light, and maintain privacy”, and earlier schemes show a number of options considered in material and finishes: a screen constructed of twisted strips, various possibilities for creeping or suckering or hedge plants, a gabion wall, an arrangement of weird fibreglass snorkellish portholes. As constructed it is a cleverly permeable wall, offering ventilation at all times as an integral part of the structure. On the day I visited, the bevelled glass edges of the new wall were catching the sun and casting rainbow stripes across the floor.

The Jubilee Oval is a pretty place. In a park dotted by massive fig trees with canopies like mushroom clouds, the oval’s picket fence is enfolded again within the curve of arched brick viaduct that carries the light rail line, and beyond that by the ridgeline and spires of Annandale. On the other side is an avenue of mature palm trees and Rozelle Bay. Looking at the building from this distance, from the direction of the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Walk, one of its quirks becomes very apparent. There is a visual confusion where you can’t really believe your eyes – is the building really on that much of a lean, or is there some kind of trompe l’oeil effect or optical illusion caused by its angle relative to the edge of the oval? Drawing closer you realize that it really has subsided dramatically to one side, a condition that posed some curious challenges for the architects. Thierry Lacoste says the structural engineer assured them that the building had moved as much as it was going to move, and so they simply worked around the lean. This would not be a restful place for those who are obsessive about their right angles, but internally it has led to an almost comical play between the new architecture’s attempt at order and precision and the decidedly wonky lines of the original. Hard decisions had to be made about which elements should line up with which, and what should be left to its own skewed devices. The result is a pleasingly rhomboid architecture, of contingency, relative to the eccentric material conditions of the world. There is also something delightfully camp about the astroturf roof, as though it had escaped from the walls of some modish inner-city bar and made its way here to lie in the sun.

Sitting there on the broad timber steps of the grandstand, it is easy to project yourself back to the time when it was first constructed, early last century – lounging through a long afternoon of cricket, looking idly upward into the elegant timber framing of the roof, the smell of crushed grass and the squinting of eyes against the glare, desultory conversation punctuated by sandwiches and thermoses of tea, the next batsman padded up and waiting for his turn at the crease. This was a man’s world, a moment of pause between the two world wars, and the building is thus an evocative artefact of another age. It is also literally a place of commemoration, with its plaques erected by the Glebe District Cricket Club, in memory of players now long forgotten. These people would have been mystified by some of the activities that take place in the park now – while I was there three women of middle years were being cajoled by a young personal trainer, using all manner of elaborate weights and elastic bands and exercises, as all the time they talked about the final of The Biggest Loser the night before. Later, a class of extraordinarily noisy schoolchildren arrived, shrieking and squawking as their teacher attempted to maintain order with a loud-hailer. At ease with its historic fabric and its bright contemporary addition, the refurbished Jubilee Oval Pavilion seems to look out at all this quite calmly, reclining on one elbow in the grass.

Naomi Stead is a senior lecturer in architecture at the University of Technology, Sydney.

JUBILEE GRANDSTAND EXTENSION AND REFURBISHMENT, BLACKWATTLE BAY PARK, GLEBE

Architect

Lacoste+Stevenson Architects—project team Kristina Mikas, Felicity Gill.

Client

City of Sydney.

Builder

Growthbuilt.

Structural engineers

SDA.

Heritage consultant

CityPlan Heritage.

Hydraulic engineer

Whipps Wood.