Until now, the building and construction industry has been able to proclaim that large developments are sustainable and “low carbon” based upon their “green” credentials, and have been fêted for energy efficiency and reductions in operational emissions. However, with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stating a goal of net zero emissions by 2050, stronger action is necessary to achieve the deeper cuts required. What does this mean for architects and developers? Is there a big green elephant in room?

Let’s take Sydney’s Barangaroo as an example. Comprising 535,000 square metres of floor space for offices, apartments, retail and a casino, no effort has been spared in attaining a Six Star Green Communities Rating and the stated goal of achieving the “the first precinct globally to be carbon neutral.” Even the Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA) is housed within Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partner’s International Towers, which were built using low-carbon concrete and steel, achieving a 20 percent reduction in “embodied carbon” (due to production of building materials and the construction process) compared with standard practice. This is coupled with use of recycled water, shading technologies, renewable energy strategies, use of 100 percent native plants and even reusable coffee cups, while 97 percent of construction waste is recycled. Barangaroo is among 19 projects around the world participating in the C40 Cities “Climate Positive Development Program.” What more can be done?

First, let’s consider the response to climate change by the building and construction industry, which is responsible for 40 percent of global material consumption and 39 percent of emissions. Embodied carbon – those emissions created in the creation of building materials, during the building process and at the end of a building’s life – account for only 11 percent and, being difficult to measure, are generally consigned to the too-hard basket. However, these are forecast to rise and form half of construction emissions by 2050. To fully decarbonize by 2050, the World Green Building Council (WGBC) launched a campaign to reduce carbon emissions from all stages of a building’s life cycle. Its new report, titled Bringing embodied carbon upfront, sets a number of ambitious goals: “By 2030, all new buildings, infrastructure and renovations will have at least 40 percent less embodied carbon…,” while being net zero operational carbon. By 2050, the report imagines, new construction/renovations will have net zero embodied carbon.

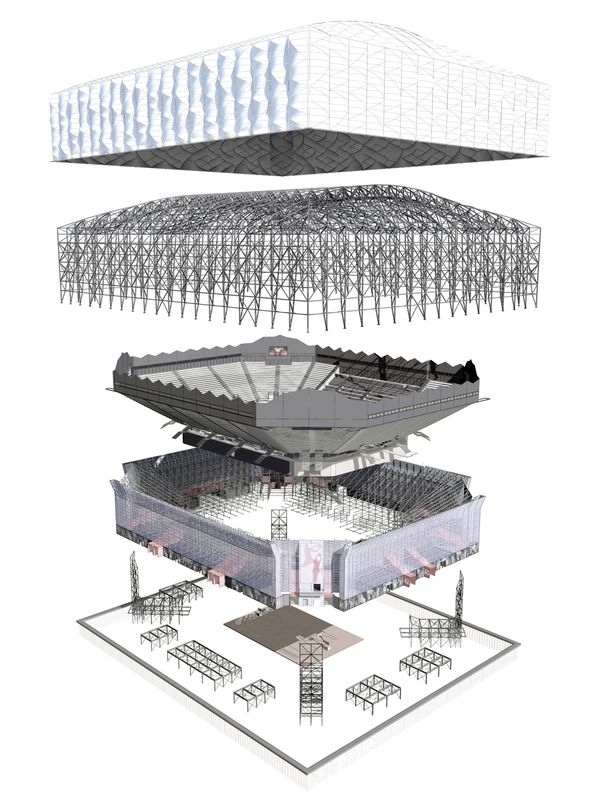

London Basketball Arena.

Image: © WilkinsonEyre

Following the lead of the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC), the report recognises that most carbon reduction potential lies at the outset of a project, including “build nothing” (questioning the need, and exploring alternative options) and “build less” (e.g. maximize use of existing assets). In this regard, the Architect’s Journal (UK) recently introduced a “Retrofirst” campaign to champion reuse and prioritise retrofitting existing buildings over demolition and rebuild. My recent book, The impact of overbuilding on people and the planet, advocated similar strategies, including better utilization, sharing and adaptation, improved asset management, and building less. The lowest carbon building is one that doesn’t need to be built.

This may be an Olympic challenge. But, as it happens, planning Paris 2024 has embraced a “build less” strategy, with 95 percent of venues being existing, while reducing carbon by 50 percent over previous games, as well as constraining cost. The LA 2028 “radical reuse” strategy goes further, with no new permanent structures in the planning. London 2012 pioneered use of demountable structures, whereby parts could be relocated, post-games, to other locations and reconfigured for community facilities. There is no doubt that buildings need to be designed for flexibility, adaptation to new uses, and an extended life within a “circular economy.” For example, the Arup Global Research Challenge 2017, involving Arup and University of South Australia, devised a web platform for exchange and reuse of components, coupled with their provision as a service. Such strategies will become increasingly necessary to constrain life cycle carbon.

It’s time for Australia to get on board. Although our cities strive for carbon neutrality, current approaches only cover emissions produced within their boundaries, mainly from electricity consumption. As C40 Cities noted, emissions associated with the production of imported goods (85 percent), including many building products, are not counted in our reporting – they are attributed to a “producing” city elsewhere. But change is on the way, with “consumption-based carbon” now recognised. When emissions are sheeted home to the final users of goods in “consuming” cities such as ours, it will be more difficult to claim we are carbon neutral.

This especially applies to construction, which is responsible for most consumption-based carbon (including embodied carbon), compared to other industry sectors. The C40 Cities group, which includes Sydney and Melbourne, has urged action to reduce consumption-based emissions from buildings by 26 percent by 2030, including: regulations and incentives to use less materials (35 percent less steel, 56 percent less cement); ensuring all buildings are used to their full capacity (a 20 percent reduction in the need for new buildings); and switching to lower-impact materials for 90 percent of homes and 70 percent of offices.

Such impending changes should put our industry on notice, not to mention our governments, policy makers and peak industry bodies. In response, GBCA’s Carbon Positive Roadmap requires that, from 2020, new buildings (excepting residential) will reduce their embodied carbon by 10 percent, commit to a performance rating, select carbon neutral products and offset their emissions. But this falls short of C40 Cities and WGBC targets. To meet its international obligations, the industry will need to commit to stronger and more fundamental changes. For example, the UKGBC’s “framework definition” already incorporates reporting of “construction carbon,” with whole of life cycle carbon next on the agenda.

To return to Barangaroo: “Is it reasonable,” as Laura Harding asked, “that a casino is constructed at all, especially on prime public land?”

“Is there a demonstrated need for such a massive commercial and shopping development, given trends towards online work and retail?” Our real estate sector, which advocates building supply first and expects demand to catch up, faces a massive challenge to achieve zero carbon buildings and build less. More and bigger “monuments to gambling and real estate” which add to the crane index, are unquestionably accepted as a good thing. On the other hand, these may further exacerbate vacancies in existing stock, consume scarce and non-renewable resources, adversely impact upon climate change, and (this is rarely mentioned) exacerbate global and local inequity.

Given that the building and construction sector is the largest consumer of resources and bears more responsibility for global emissions than any other sector, can we lift our sights from green window dressing to make the strong and fundamental changes required to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, while supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals ‑ including “Responsible Consumption and Production.”

Dr David Ness is Adjunct Professor, School of Natural and Built Environments, University of South Australia, and former editor and publisher of Building + Architecture Magazine, the official journal of Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ South Australian chapter during the 1980s.