REVIEW JOHN DE MANINCOR

PHOTOGRAPHY MICHAEL NICHOLSON

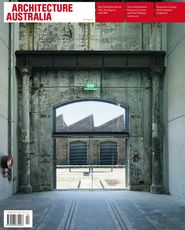

The entry to the new centre for physical theatre and contemporary dance within the Eveleigh Railway Workshops precinct in Redfern, Sydney.

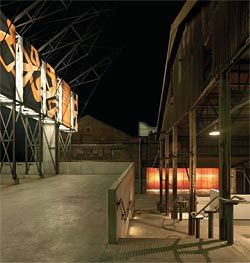

Looking down the entry stairs from the new street-level plaza, with the glowing entry structure to the left.

The signage structure, as seen from the street.

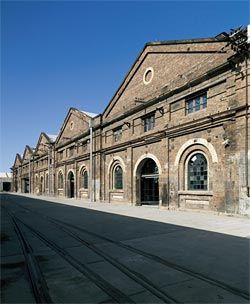

The brick facade of the original late-Victorian industrial building, which houses the new performance space.

Looking into the main foyer space, with the entry to the left.

The main foyer during the Sydney Festival.

A junction between old and new.

The main foyer showing entry to Bay 19. The roof-light allows penetration of natural light.

CarriageWorks is a new centre for physical theatre and contemporary dance within the Eveleigh Railway Workshops precinct in Sydney’s Redfern. The project is the result of nearly $50 million of investment by Arts NSW, the body responsible for managing the state government’s cultural investment portfolio. Government investment on the site began in the late 1870s, and over the next ten years an impressive array of industrial buildings were erected. Many of these remained in use until 1988, when the production of rolling stock was privatized. Beyond the returns of 100 years of production, the workshops were a major employer and played a signifi cant part in the development of the surrounding suburbs. As such the government’s fi scal outlay infl uenced the evolution of local culture.

Depending on our socioeconomic background, the words “investment” and “culture” may bring to mind a range of different ideas and ideals. An important link between the two terms is the premise that an essential undertaking of a developed, civilized society is investment in cultural infrastructure. Capital works projects such as Queensland’s GoMA, Melbourne’s Federation Square and Sydney’s Opera House are testament to this ideal. In the fi nancial arena, the higher the investment risk, the higher the return. Risk may be seen in a similar way in the performing arts.

Experimental theatre is not for all, it can be challenging and confronting, it is the risky end of the performing arts spectrum, yet it generates culturally rich returns.

The new centre occupies part of the former Carriage Workshop. The workshop is a fabulous example of late Victorian industrial architecture, considered to be of exception heritage value by the NSW Heritage Offi ce.

Beyond the ornate brickwork, elegant cast-iron columns and slender steel trusses, the signifi cance of the building lay in its spatial qualities – vast, cathedral-like spaces that whispered of a bygone era. The embedded history of the space was seen to be as important as the fabric itself. History plays an important role in the ongoing development of a culture. The built environment is one means by which we can read the past, while new architecture and the reworking of existing building stock allows future generations to read a society’s vision of the future. The future in turn becomes the past, and so the cycle repeats.

Interwoven within and occasionally bursting through the existing building fabric are a series of gusty new interventions by Tonkin Zulaikha Greer (TZG).

The work is a continuation of the raw and inventive approach to adaptive reuse evident in earlier projects such as the Powerhouse Regional Arts Centre in Casula and Hyde Park Barracks Museum. The programme comprises two fl exible theatre spaces (800 seats and 300 seats respectively), rehearsal spaces, training rooms, offi ces and large scenery workshops. It will be home to a number of companies, including Performance Space, Marrugeku, Stalker, Theatre Kantanka and Erth.

Sitting one level below the street, the workshop building was dislocated from its urban context, with no public address. A new plaza has been created at the upper level, housing a major signage structure composed of concrete blades and recycled roof trusses. The structure terminates the view along Codrington Street and signifi es entry into the precinct. Beyond this space, the external form of the main theatre reads as an undulating lantern, slicing through the rhythmic pitched roofs of the workshop structure. It was the subject of heated debate among the numerous committees involved in the approval process. Various opinions were espoused on its form and whether modifi cations to the envelope should be permitted at all.

According to TZG project director Tim Greer, one of the most important goals for the project was to maintain and stabilize the existing fabric for future generations. In addition to the roof debate, there was signifi cant pressure to retain the internal open space intact. The decision to occupy the space with such an ambitious programme meant the end of a spatial era, and heralded the beginning of a new one. Reuse in any form guaranteed the future of this industrial relic, albeit in an altered state. Greer cites an admittedly unusual quote from soul singer Bill Withers when taking about preservation of the structure, “I want to spread the news that if it feels this good gettin’ used, just keep on usin’ me until you use me up.” In other words, if occupation results in modifi cation instead of devastation through neglect, then so be it.

Entry into the complex itself is via an original opening through which countless thousands of carriages once passed. Now glazed and embellished with bold interpretative graphics, it denotes a new threshold to a new era of occupation. The generous foyer space reveals a key strategic approach to the project. Five rectilinear concrete containers are arranged parallel to the dominant rhythm of the existing structural grid.

They read as objects in space as if they were “made” in the factory that now houses them. All bar one sit under the existing roof. In an apparent gesture to the new, the old roof opens up to allow the largest of the performance spaces to pass through. The space between allows natural light deep into the plan and aids in passive ventilation through a stack effect. Where original fabric has been removed to make way for new work it has been relocated and reused. Columns from one bay now support a mezzanine within the main auditorium and a series of roof trusses for a playful structure that denotes entry to the entire precinct.

The rawness of the new structures echoes the industrial qualities of the 1880s fabric. The concrete containers were initially conceived with patterned surfaces; however, the fi nal unadorned off-form concrete surfaces seem more successful. They allow the rich pattern (the existing cast-iron columns are quite ornate) and patina of the original to take precedence over the new. While these material qualities have their own inherent value as a means of reading the evolution of the place, it is the in-between spaces that are the most exciting. Here a more intimate and tactile interaction with the various layers of building fabric is possible in spaces that facilitate accidental meeting.

The top-lit corridors that surround the main theatre are particularly dramatic. Internally, the theatres and rehearsal areas are as tough as the exterior. Each is planned around a grid of rigging structures that allow rehearsal spaces to mimic the performance venues in a variety of configurations.

CarriageWorks is a vital piece of cultural infrastructure where nearly anything can happen.

To date it has hosted local and international dance performances as well as a raucous album launch by Silverchair and the chucking of 300 dozen oysters as part of an installation by Sydney artists Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro. More importantly, it is paying dividends for its investors – culturally speaking, of course.

John de Manincor is a principal of de Manincor Russell Architecture Workshop (DRAW) and teaches at the University of Technology, Sydney.

The rigorous structural grid of the original building is maintained. Looking down one of the corridor spaces, showing detail of the cast-iron columns.

Detail of the entry to Bay 17.

Stair detail.

Looking into the medium performance space from above.

Interior of the medium performance space (Bay 20).

Primary Producers, March 2007, by Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro. Curated by Sally Breen. Photograph Heidrun Lohr.

The office spaces on Level 3.

The office lobby.

EVELEIGH CARRIAGEWORKS, REDFERN

Architect Tonkin Zulaikha Greer—project team Tim Greer, Julie MacKenzie, Jeremy Hughes, John Chesterman, Trina Day, Bettina Siegmund, Amelia Holliday, Vanessa Vorster.Project manager Root Projects.Quantity surveyor Currie and Brown.Heritage architect Otto Cserhalmi and Partners.Structural engineer Simpson Design.Services engineer Bassett Consulting Engineers.Hydraulics engineer Warren Smith and Partners.Acoustics engineer Arup Acoustics.BCA advisor City Plan Services.Fire engineer Defire.PCA Advance Building Approvals.Access Accessibility Solutions.Theatre and lighting consultant Bluebottle.Graphic designer Jelly Design.Community consultation Australia Street Company.