Being in Japan during the longest solar eclipse of the twenty-first century was intriguing. There seemed to be a galactic flurry of excitement in the air, a supernatural glow of anticipation. Some couples had even planned trips to obscure islands where they were preparing to experience the historical occurrence (all six minutes and thirty-nine seconds of it) to full effect in matching Gore-Tex camping suits. The romantic spell cast can only be attributed to a rare meeting of science and spirituality with spectacle.

This is the exact recipe channelled by Japanese artist Yukinori Maeda when he founded Cosmic Wonder in 1998. Begun as a collaborative art project in 2007, the idea was woven into Cosmic Wonder Light Source, described by the group as “a product composed of positive spirit and physical materials reverberated with the light of the natural world.” Read: fashion label.

Meandering through the backstreets of Aoyama amid a summer downpour, I happened upon The Center for Cosmic Wonder: a cavernous space that welcomed visitors through a handle-less door propped open by a fake meteorite. As I approached I wondered if it was some kind of new-age planetarium or perhaps a day spa for the imagination. All I found was a single projected video of a group of wholesomely attractive young men and women wearing stylish clothes and acting out what seemed to be an office scenario. Some of them walked around reading books; others made notes and shuffled papers.

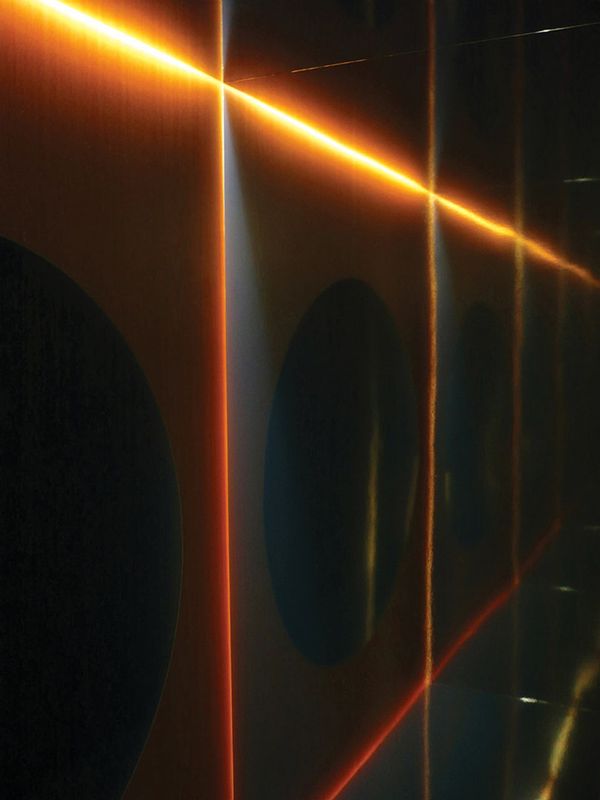

An opening in the corner of the room led to a second space and a footpath of concrete stepping stones within a courtyard garden. Feeling as if I had entered a private space I turned to leave but found myself caught in a shaft of refracted gold light and a third doorway: the almost hidden entrance to a shop. In here I was overcome by a distinct lack of stuff. A classic cool Japanese treatment of space - just as you might arrange a sparse Ikebana, this room seemed almost empty, but with close inspection was in fact rich with detail. Birdsong played in the background and a Japanese man in a grey bow tie greeted me softly. In the middle of the space was a kind of rack that appeared as if a piece of space junk had been adapted to serve some new purpose here on Earth. Hanging from the rack was a pair of wearable eclipses made from gold and silver fabric: ponchos of light. At this point something clicked in my mind, maybe the planets aligned. Either way, I had come full circle in my understanding; the purest of retail experiences is akin to that of an art experience - it requires empty space for thought, contemplation and wonder.