Detail of one of the wind turbines crowning the building. Image: Dianna Snape

Detail of the east facade. Image: Dianna Snape

Oblique view of the north facade balconies. Image: Dianna Snape

Looking along the Little Collins Street facade, with the shower towers lit. Image: Dianna Snape

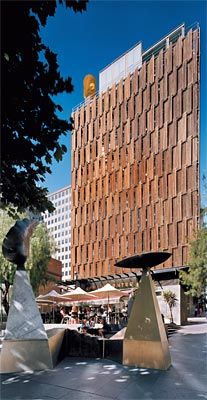

The west facade as seen from Swanston Street, with shutters open. These automatically open and close in response to sun angle and time of day. Image: Dianna Snape

The west facade, with shutters closed. Image: Dianna Snape

The roof terrace is lined with wind turbines and features David Wong’s rock art installation. Image: Dianna Snape

Open plan office space. Image: Dianna Snape

Looking down onto the foyer space, with an artwork by Janet Laurence seen on the far window. Image: Dianna Snape

Downtown Melbourne has just hatched a cuckoo.

Its central business district is now home to an office building very different from the array of other edifices that the city has recently given life to. The cuckoo is CH2, the City of Melbourne’s Council House No. 2. Although the building is in no way a form of hydrocarbon, its quirky name is significant in giving the public a glimmer of insight that this building is quite different from those surrounding it.

The building is probably Australia’s first urban example of an architecture that is directly based on biomimicry. Every aspect of the building has been examined and rethought from first principles, evolving new precepts that are based in the desire to be as true as possible to the fundamental “laws of nature”. The design philosophy is concerned with developing appropriate architectural responses that are a direct and honest expression of the biodynamic relationships that nature uses in her own designs.

This has implications for the building’s architectural form and for all the very sophisticated engineering within it. The composition of this building – its skin, its bones, its very innards – has been subjected to rigorous reappraisal to attune it to natural processes. This acknowledges the reality that we, as a society, must develop more sustainable structures to live and work in, if we are to survive as a species.

CH2, located in Little Collins Street and overlooking Swanston Street, rehouses various departments of the City of Melbourne in new, open-plan accommodation. The building set out to showcase advanced sustainable design and to achieve a six-star energy rating. The City of Melbourne believed that the best way to lead was by showing just what is possible – the final building is a working demonstration of a wide variety of different engineering principles, all of which contribute in some way to obtaining long-term environmental benefits. One of these, the development of the phase change medium that stores heat energy, is truly groundbreaking in its degree of innovation.

The architectural design that guides this engineering is the result of a thorough re-examination of the fundamental requirements of the twenty-first-century office, and how these functional needs can be best met on the limited site available. Essentially, the building’s layout is a floorplate free of internal columns, repeated and stacked ten storeys high, with public lifts and stairs at the south-western end looking over Swanston Street, and a service core to the north-east of the open interior, which also shields against direct solar gain.

So, in addition to answering the technical issues, does CH2’s design approach address the formal precepts of being appropriate architecture, as opposed to merely being good building? For me, the answer is an overwhelming yes.

Mick Pearce, CH2’s creator along with DesignInc, has based his entire professional career on creating buildings that take their fundamental design thinking directly from nature. Educated at the Architectural Association in London, Mick has spent most of his working life in Africa, especially in Zimbabwe, where there are obvious and real limitations to the ongoing deployment of many of the mechanically based building technologies taken for granted in the West. Mick has evolved appropriate designs for urban African office buildings, with solutions modelled directly on what nature does in the same situation. Prior to CH2, he completed a large office project in Harare, based on the monumental termite mounds that populate the open savannah. The building exactly mimics the way these huge organic towers elegantly resolve the basic issues of heating and cooling, indeed of all life support systems, for their tiny inhabitants. Now Mick has adapted his thinking to a tight urban site in downtown Melbourne, showing how it is possible to insert a design based on biomimicry into an artificial urban environment. DesignInc’s Stephen Webb and Chris Thorne worked with Mick, helping to make it a very Australian building.

One of the measures of assessing a building design based on biomimicry is whether it successfully shows its innate qualities as a visually resolved architectural form, rather than as a box full of eco-tech objects.

CH2’s public face is the tall facade overlooking Swanston Street, one of Melbourne’s great public boulevards. It is entirely composed of timber vertical slats covering a fully glazed wall. These slats pivot vertically, opening and closing in response to the time of day and the angle of the sun.

The facade is thus animated in direct response to the external conditions. This is biomimicry at its very best – the building moving and becoming alive in response to the conditions surrounding it. The facade also highlights a material normally banned from the CBD, timber (in this case, all recycled), showing that traditional natural materials do have a place in the new urban Australian landscape.

The building’s crown houses another element that aptly announces the design philosophy. Six huge, bright yellow wind turbines are a fitting visual tribute to the way air moves around CH2’s interior, proclaiming way this building harnesses another powerful natural resource, wind. Near the location from which Ron Robertson Swann’s “Yellow Peril” sculpture was ignominiously removed several decades ago, these similarly coloured, large metal objects announce a very different set of sculptural values – engineering as public art – with the mechanical forms used in the harnessing of nature given a real visual prominence.

What is even better is the fact that the generator inside is a direct adaptation of a domestic washing machine motor. Could there be a more appropriate symbol of an intuitive, adaptive design (and one that seems so very Australian)? These large turbines top the building in much the same way as turrets and spires have traditionally done, and they make a similar contribution to the downtown urban roofscape, especially when one looks up Swanston Street from Flinders Street Station.

Internally, the visual character of each of the open floors is shaped by the large, wavy precast concrete ceiling/floor elements that undulate overhead. Part inner duct, part large surface of exposed high-thermal-mass material, these elements define the open workspace below. Interestingly, the light levels have been kept reasonably low, and low-energy tabletop task lights sit on every desk, to be used when higher light levels are required.

In the first weeks of the building’s occupation, it is this aspect that is drawing favourable comments from the staff, who were apparently apprehensive about shifting to such an open workplace. The combination of individual lights and softer overall lighting levels has been rated highly by users – they say it makes them feel secure, further testimony to the benefits of giving people at least some degree of control over their surroundings. Plants also figure prominently both inside and out. The provision of vertical frames for climbing plants as “living sunscreens” on the north-west facade and the upper roof terrace will mean that the building will become literally alive and green.

This is a very important building, not just for its innovative engineering, but, far more significantly, for the way that every single design element, both spatial and non-spatial, has been resolved and integrated to reinforce the concept of creating a unique solution that mimics nature. The resultant sum is far, far greater than the mere addition of its constituent parts.

CH2’s environmental aspects are the subject of the Practice pages of Architecture Australia, Jan 2007, 96/1, see pp 101-104.

Credits

- Project

- CH2

- Architect

- DesignInc

Australia

- Project Team

- Mick Pearce, Stephen Webb, Chris Thorne, Jean Claude Bertoni, Aldona Pajdak, Jacinda Thornton, Rob Adams, Robert Lewis, Shane Poswer, Matt Plumbridge, Kate Gorman, Kate Senko, Ione McKenzie

- Architect

- City of Melbourne

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustics

Marshall Day Acoustics

Artist Janet Laurence, Cameron Robbins, David Wong.

Builder Hansen Yuncken

Developer City of Melbourne

Environmental engineer Advanced Environmental Concepts

Interior design DesignInc, William Morgia, DesignInc, City of Melbourne (Aldona Pajdak, Juliet Moore

Landscape City of Melbourne

Quantity surveyor Donald Cant Watts Corke

Services engineer WSP Lincolne Scott

Structural and civil engineer Bonacci Group

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Budget $51,000,000

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2006

- Client

-

Client name

City of Melbourne

Website melbourne.vic.gov.au

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jan 2007

Words:

Robert Morris-Nunn

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2007