Text Peter Crone

Photography Peter Bennetts, Patrick Bingham-Hall

N°1 Stair in the Chadwick House from entry hall down to the lower level. The storage box/seat can be seen under the bay window. Redwood wall cladding has been restored.

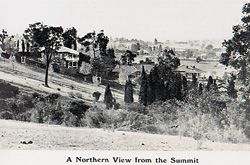

N°2 Archival image showing the three Desbrowe-Annear houses at The Eyrie.

N°3 Entry elevation, showing the restored colour palette. The garden is affected by drought.

N°4 Entrance verandah, with views to the east framed by the swagged ogee arch and slatted balustrade. The hopper and sash windows are seen by the door.

N°5 The leadlight has been attributed to artist Blamire Young, a friend of Desbrowe-Annear.

N°6 The house as purchased by Peter and Jane Crone in 1988, with its black-and-white “pseudo-Tudor” colour scheme.

N°7 The north-west corner, showing the disparate windows and door added prior to the Crones’ purchase.

N°8 The main living room as found – the lower walls covered in fibrous plaster, doors and window painted in gloss enamel, and the fireplace with brick front and mirrors above.

N°9 Peter Crone at work. Eleven sliding sashes and four hopper windows had to be removed to allow complete paint stripping.

N°10 Removing the false ceiling in the large downstairs room revealed the original exposed Oregon beam structure and Californian redwood lining below the upstairs jarrah floorboards. The whole ceiling area void had been packed with sawdust, possibly for insulation.

N°11 “A well deserved glass of wine after another day of toil.” The kitchen is in its 1950s state, with original windows gone and masonite covering the original timber wall lining.

I first became aware of the work of Harold Desbrowe-Annear around 1964 when, as a student of architecture at RMIT, our design class led by Kevin Borland visited Eaglemont to walk around Walter Burley Griffin’s Glenard Estate (Pholiota, c.1919–20; Griffin’s own house; and Lippincott house, 1917, from Griffin’s office) and the Mount Eagle Estate (Griffin’s Skipper house, 1928), along with the adjacent Eaglemont Estate, within which three Harold Desbrowe-Annear houses were built.

Piqued by the exteriors of the Annear houses, my interest led me to read Robin Boyd’s Australia’s Home, in which he refers to Annear’s inventive approach, in particular within the field of domestic building, where “he saw the greatest scope for the inventiveness and love of gadgets which so filled his mind in his younger days. Every new commission for a house was an invitation to experiment with a new device for a window or a cupboard or a detail of construction.”

Geoffrey Woodfall’s essay on Harold Desbrowe-Annear, “Documents on Australian Architecture”, published in Architecture in Australia in February 1967, further stimulated my interest in Annear, particularly the large number of published photographs of his projects. This work also reproduced construction details published originally in For Every Man His Home, coordinated by Annear in 1922.

Twenty years after my “discovery” of Annear and after a progression of renovations and additions to Victorian terrace houses in Carlton, followed by a restoration and upgrade of a large Edwardian timber villa in Fairfield, my wife Jane and I, sick of DIY projects, discussed the possibility of designing a new house for ourselves if we could find suitable land, with a provision that if one of Annear’s houses ever became available then we would attempt to acquire it.

Amazingly, within a week of this discussion, we discovered that our favourite Annear house, one of the trio in The Eyrie, Eaglemont, was due to be auctioned shortly. This house was designed for Annear’s father-in-law, James Chadwick, in 1903 and is today referred to as the Chadwick house.

Armed with our rose-tinted glasses, we attended an inspection in June 1988 and confirmed our desire to make it ours. The auction, attended by about four hundred people including many architects, was an incredibly charged affair. A close friend – a Queen’s Counsel at the time – took to the bidding war with relish, refusing to let the momentum get away from him. He finally submitted the winning bid – approximately 30 percent higher than our contemplated maximum. Nevertheless, it was obvious to him that we had to have the property.

Enthused by the house’s architectural, social and historic importance (but less enthused by our considerable mortgage) we embarked upon the amazing experience of restoration in November 1988. Most of the work (except for the plumbing and electrical works) has been carried out by Jane and myself. Our intention has been to thoroughly restore the fabric of the building in accordance with the principles of the Burra Charter, where, as faithfully as possible, new work is subtly identified from the original. Prior to carrying out the work, it became obvious that a detailed investigation of the entire structure and finishes needed to be undertaken – at the outset, we had dismissed most of the “improvements” to the building as careless vandalism, but further inquiry upgraded our detective work to a murder investigation.

Prior to settlement, I perused the Heidelberg Conservation Study written for the then City of Heidelberg in 1985. One statement within the study referred to the various external elements where the “overall picturesque disposition of elements have been borrowed from northern European 14th and 15th century styles. These are exemplified in the white roughcast and black-stained timbering (i.e. the black and white houses).” No reference was made to the Arts and Crafts movement. During a visit to the house, I observed that beneath some flaking white paint on the external roughcast render there was a hint of colour.

As soon as we became the legal owners I proceeded to strip away small sections of the paint throughout the exterior. The half-timber battens of the exterior walls were indeed originally black, having many coats of coal-tar stain. My suspicions that the house was much more than “pseudo-Tudor” were confirmed by a highly regarded conservation architect, who determined from my scraping samples that the house colouring comprised a rich colour palette often found on English and North American Arts and Crafts houses, with the render matching Porter’s Boncote Suntan colour. The original colour of the windows’ external timberwork, the swagged ogee arches and slatted balustrading was identified as a rich cream-ochre colour. The horizontal double-bevelled weatherboards were a rich dark brown.

Further investigation has revealed that the property’s other two Annear houses were painted in an identical colour scheme. Along with the Officer house, the Chadwick house has had its original Arts and Crafts colours restored. The remaining house – Annear’s own – is about to be repainted from its current black-and-white scheme.

Crawling through the sub-floor and ceiling spaces revealed much of the history of the building. I was amazed to find that all the wall studs continued as free ends up into the ceiling space with no top plate. Further investigation unearthed a complete framing system that used the North American “balloon frame” method of wood construction, where long continuous framing studs run from a bearer/bottom plate with the studs tenoned into the ceiling joist line. Intermediate floor and ceiling structures are supported on offset beams checked in and nailed to the studs.

As there are no noggings, Annear was able to utilize the modular stud spacings to accommodate operable windows – a cleverly designed offset hinged hopper window above the sash window units, which slide up into the wall cavity, counterbalanced by a common house brick in a wire cage and connected by a single sash cord threaded through a series of pulleys. The location of some of these pulleys in the roof space revealed the original locations of sash windows that had been replaced over the years with inappropriate alternatives. Work over the last twenty years has seen eighteen sash windows and hoppers rebuilt and installed by myself. These sashes are now complete, with the reinstatement of lost wax brass castings of all the original Annear fittings, comprising sash lifts, spring-loaded hopper catches and bell-shaped covers located over the cord knot at the top of each sash.

One of my early projects was to restore the fireplace mantle and walls in the main living room and entrance hall. The original sequoia (Californian redwood) panelling and window brackets, along with the entire fireplace surround and overmantle, had been removed and replaced with fibrous plaster. All remaining skirtings, architraves, cavity sliding doors and windows had received multiple coats of white gloss paint, which was, slowly and with a lot of patience, stripped to enable repolishing of the timber beneath. I was fortunate to discover sufficient lengths of twelve-foot-by-two-foot sequoia in an old timber yard that were machined to match the original profiles and thickness required for the panelling. Fragments of the original overmantle were discovered beneath the house, which provided clues for recreating the details.

Work on the living room took more than eighteen months of weekends and spare evenings. Throughout our twenty years of completing stage one of the restorations, no drawings or photographs of the original house have been discovered.

The entire internal fabric of the original kitchen and bathroom was restored, with freestanding elements inserted to provide the amenity of contemporary living. The restored walls have been left without any intrusive components. Future upgrades of equipment and services can be undertaken without affecting the fabric of the spaces. Removal of masonite wall linings in the original kitchen and pantry revealed Baltic pine lining, with painted areas defining the location of the original shelves, brackets and architraves. These were recreated in their original configuration. An internal paint colour study determined that painted timber linings and windows to the kitchen, breakfast room and study were the same cream/ochre as the external trim.

With stage one completed, we are now starting to address the removal of the inappropriate billiard room addition (1920s) at the rear (north side) of the house, which will allow us to complete the project. Considerable ongoing maintenance will ensure that the vision of Harold Desbrowe-Annear is preserved for future generations to experience and enjoy.

Peter Crone, LFRAIA, is the principal of Peter Crone Architects. Chadwick house is on the register of the National Estate as a “registered place including house and grounds”, and is also registered by Heritage Victoria and classified by the National Trust in a group classification that includes the houses and their sites, together with the landscape of The Eyrie from The Panorama to Outlook Drive. In 2008 the house won the Australian Institute of Architects Victorian Chapter John George Knight Award for Heritage and an Australian Institute of Architects National Award for Heritage.

N°12 Completed living room. The detail for the fireplace mantle came from two pieces discovered under the house and from the original backing board, found behind the mirror. The blue plaster is an exact match to the original colour, which was identified from a plaster sample and paint on top of the plate rail.

N°13 Dining room. Minimal damage made this the most original room in the house. Fireplace details matched the living room and could be used as a template. A built-in server with small hatch to the kitchen is seen to the right.

N°14 Sash and hopper windows in the spare bedroom. The centre sash is open, with sash cords visible on the other windows. The lower frame of the hopper coincides with the upper sash member. Behind the rocking chair is the original brick hearth, the only clue to the fireplace. The brick arch exists behind the panelling. The mantle will be rebuilt in the future.

N°15 Lower-level storage and model making room in completely original condition. The Kauri shelving and bracket detail provided clues to shelving details in other utility areas, for example the pantry and kitchen.

CHADWICK HOUSE, IVANHOE, VIC

Architect

Peter Crone Architects—design architect Peter Crone. Original architect Harold Desbrowe-Annear.

Builder

Peter Crone.

Photographs

1, 2, 11–14 Peter Bennetts

3, 4 Patrick Bingham-Hall

5–10 Peter and Jane Crone