Working at the intersection of architecture, city planning, art and urban intervention, Berlin’s Raumlabor collective combines the experimentation of art practice with realizable architectonic forms. They produce often temporary works that act as social activators, suggesting new ways of interacting with the city and its people.

I first came across their work while living in Berlin, where their architectural interventions would appear in surprising places, attached to existing buildings or inserted into the spaces between, reflecting the changing urban condition.

Outside the (then) soon to be demolished East German parliament building, they erected a hotel and mountain (Der Berg, 2005), offering an alternative way to experience the last days of this controversial structure. Their transparent inflatable structures, such as Rosy (2010) would appear at parks and festivals, creating intimate spaces in which to congregate. Internationally, raumlabor has been included in countless architecture exhibitions and biennales, and their research into urbanism and critical practice is highly regarded.

Their “Generator” series of mobile structures has been produced collaboratively worldwide and its latest incarnation was created for Raumlabor’s Sydney exhibition, User Generated Architecture.

Joni Taylor: Raumlabor is a collective of eight trained architects, yet you often work with collaborators from other fields. How did this come about and how does it function?

Christof Mayer of Raumlabor.

Image: Dianna Snape

Christof Mayer: Raumlabor was never founded in a classical sense, it happened. It developed out of sharing experiences, experience we had in the 1990s of post-wall Berlin. As a collective we developed a flat hierarchy and a simple structure of working together – usually only two or three of us share a project, so we always have a dynamic working situation and diverse dialogue. Although we all are trained architects, we all have different interests and different approaches to architecture, which is why we describe our work as “at the edge of art, architecture, performance and urbanism.” As a consequence of this, it is obvious to open our practice to diverse collaborations that go beyond the obvious (engineers, for example) and try to engage artists, musicians, sociologists or ethnologists on the one hand into our work process and the ‘user,’ or as we like to call them, ‘local experts’ on the other.

Raumlabor’s Rosy the Ballerina, London, 2010.

JT: How do you encourage public participation in your work?

CM: Very often we create possibilities for people to engage themselves. Another strategy is to provide spaces in public to create temporary communities – such as Rosy (London, 2010) or Spacebuster (New York, 2010) – which we call “mobile urban activators.” These provide spaces in almost any urban context for up to 200 people. Other times our work is not visible, but it tries to create frameworks for structures of empowerment like what we did for the Tempelhof project, which is about the redevelopment of the former airport in the inner city of Berlin.

JT: The Tempelhof Airport is a historically charged site, famous for it’s architecture, the Berlin airlift and now its redevelopment. You were involved in the research into possible future uses. Please explain a bit about this research side to your practice?

CM: Mostly we are asked by municipalities to work on different issues of urban development, and sometimes there is a brief. It’s more interesting for us to work out the problems in the first phase, and try to raise general questions to be more relevant.

JT: So what did your research uncover in the Tempelhof project, and more generally, what is the role now of architecture and architects for this site?

CM: We were commissioned from the senate office of urban development as part of a working partnership to do a study about the future development of the airport after its closure. We developed an alternative approach to the urban development of this area by linking top-down with bottom-up processes and connecting long-term and short-term issues, creating what we called a dynamic masterplan. Some of our initial ideas were compromised after long discussions with our client. The problem with studies are that once finished you do not know if they go straight to the archives, or what is going to be used in what context. Right now we are in the situation where only after five years are the politicians beginning to understand that the situation is really unique and that people really love this spot. At the same time there are competitions for housing developments for the area, which are being challenged by an initiative to keep the whole area open. It’s really interesting how people use political means to make claims for their city. As you can tell, architecture does not play an important role at the moment.

JT: I am interested in this emphasis on time for urban planning and architecture. What can we learn from slow incremental development processes, rather than “instant” cities?

CM: I would not make a distinction between incremental planning and instant cities, because I think the latter should be part of the learning process. This means that we think there should always be an open phase for experimentation, to make mistakes, and to see what works the best.

JT: So what examples can be given to persuade urban planners that this is a successful method?

CB: This is pretty tricky because I think it depends to some extent on your convictions and beliefs and the issues you follow. Obviously the best arguments are always other successful examples, but then there is still the question of how you define success. We don’t think that it is wrong to have a masterplan as a basic framework, but we are convinced that there is another layer that highlights the process from the beginning, starting with instant interventions from which to discover something about the existing conditions. We call this the strategy of the Venetian bridge.

JT: You often create these site-specific interventions that only last for a short time. What is the importance of facilitating this temporary architecture?

CB: For us they are tools to explore urban space, to create short-term communities using dialogue and exchange and at the same time they attract a lot of attention, which is really helpful to develop our projects. Beyond that they allow one to inhabit difficult public spaces that were never thought of. And finally they encourage people to think about their public spaces.

User Generated Architecture exhibition of Raumlabor, Tin Sheds Gallery, 2013.

JT: How can exhibitions be effective in communicating ideas about architecture and urbanism?

CM: Exhibitions are always an opportunity to reflect on our ideas, work on the issues and communicate and discuss them in different contexts.

JT: The Tin Sheds exhibition you are included in is entitled User Generated Architecture. How can non-trained “users” affect the development of a city?

CM: I think our contribution to the exhibition is more about User Generated Urbanism than User Generated Architecture. Of course we use architectural means to explore urban situations, but we understand this more as a tool to act within an urban context. For example in the Sydney Generator we use architecture as a means to engage people in public space and encourage them to claim their city, sometimes this means to prove that public space is not only about consumption and commuting or transiting. At its best, people start to understand that there are different possibilities to engage.

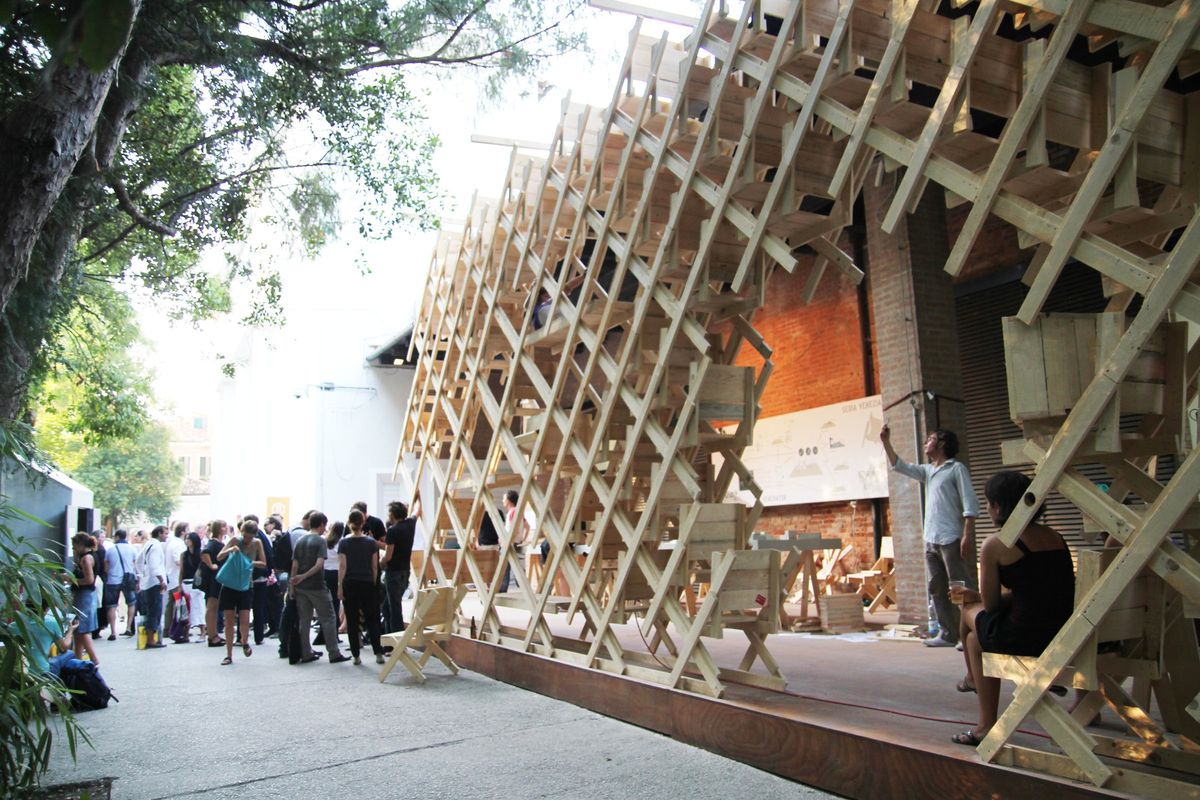

Raumlabor’s The Generator, Venice, 2010.

JT: What are the ideas behind the Sydney Generator and what were the outcomes?

CB: The Sydney Generator is a part of our Generator projects which are about the temporary inhabitation or occupation of public space. To facilitate this we develop and produce different modules, usually furniture as a basic thing to create community and communication. The Sydney Generator is a more abstract module that could be arranged in many different ways. We asked the participants to be inventive about the uses. The production of the modules is always an essential part of these workshops as it shows people that they can create something by themselves. Another part is a sketchbook, that we prepare, that describes the generator, how it is assembled and how it could be used, but only as an inspiration. In this workshop we produced about fifty modules, which we first tested in front of the gallery before we decided to try some guerilla-style interventions in real public spaces. It was then reconfigured as a kitchen and we cooked and shared food.

The exhibition “User Generated Architecture - raumlabor berlin” continues until 15 November 2013 at the Tin Sheds Gallery in Sydney as part of the Sydney Architecture Festival 2013.