In October 1967, Tasmanian Catholic Archbishop Sir Guilford Young consecrated the Church of the Incarnation in Lindisfarne on Hobart’s eastern shore, the state’s first new, post-Second Vatican Council church. Commissioned by the parish priest, Father Michael Flynn, and designed by parishioner and architect Lindsay Wallace Johnston, the church has been overlooked in the slight histories of modern architecture in Tasmania. The state’s postwar ecclesiastical developments have typically been represented by the technological and metaphorical form-making of J. Esmond Dorney’s Pius X Catholic Church in Taroona (1957) and Cooper and Vincent’s St Patrick’s College Chapel in Launceston (1959). The design of the Church of the Incarnation presented an economical brutalist alternative. For Young, Flynn and Johnston it was a radical attempt to realize a liturgically driven, non-monumental, modern church architecture that aimed to build community. For the editor of the Australian Catholic journal Madonna , the result was a “dream.”1

The Church of the Incarnation is of interest among the variants of brutalism in Australian architecture for its apparent alignment with the particular progressivist ideals of New Brutalism as defined by British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, and theorist Reyner Banham, from the mid 1950s. Its aesthetic sensibility is undergirded by an abiding ethic guiding the building’s image, structure and materiality.

Archbishop Guilford Young commenced his episcopate in Hobart in 1955, embarking upon a program of modernization and reform in the areas of church administration, education, worship and church building. He had a keen interest in architecture, but worked within a context of limited financial resources coupled with a growing demand for new churches. As he consecrated new churches, including Dorney’s Pius X Catholic Church, Young advocated “healthily modern” church architecture and, in 1958, he appointed Roderick Cooper, of Cooper and Vincent, as diocesan architect and began commissioning individual as well as standardized designs for modern churches for new industrial and housing commission subdivisions.

The building was commissioned during Tasmanian Catholic Archbishop Sir Guildford Young’s program of modernization and reform in church administration, education, worship and church building.

Image: R. Farrington c. 1967, courtesy of Paul Johnston

Young’s interest in modern architecture was allied to an international liturgical reform movement. The goal was to develop an architecture to aid in modernizing worship; this was approached in the fan-shaped planning of Cooper and Vincent’s soaring St Patrick’s College Chapel. The wider discourse posited that the essential function of a church building was to accommodate the performance of the liturgy, and especially the Eucharist, which was understood as an action involving the clergy and the congregation as a community. As outlined in Peter Hammond’s widely read book Liturgy and Architecture (1960), the task of the modern church architect, therefore, was not simply to develop a contemporary church idiom through the application of modern methods, but rather to generate architectural forms that embodied contemporary understandings of the liturgy and community.

Young advocated this task to the architectural profession. At the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ national convention in Hobart in 1960, he performed a Mass for architects, delivering a sermon on contemporary liturgical architecture. He advised his congregation that arriving at a modern church architecture would involve both scholarship and participation in the liturgy and community. He rallied against traditionalist church design while reasserting the church’s patrimony in architecture: “Liturgical in mind and spirit, the modern architecture will be saved from modernity for the sake of modernity.”2

In 1965, key tenets of the Liturgical Movement were ratified by the Second Vatican Council, providing the imprimatur for the realization of Young’s progressivist views on church architecture in Tasmania. In the new parish of Lindisfarne, Father Michael Flynn commissioned Johnston to design and superintend a new church.

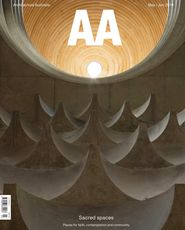

Johnston’s design for the Church of the Incarnation comprised an arrangement of concrete block prisms, presented in the local press as a comprehensive functional, aesthetic and social response to Second Vatican Council liturgy. A single interior volume, a sloping floor and open sanctuary were to unite the clergy and congregation in the liturgy. An interior palette of unfinished concrete block, timber and plywood was to maintain focus on liturgical proceedings. All “pretty stark,” as Flynn explained: “We have made a deliberate attempt to get away from the idea of a church as a monument … We’re trying to get back to the idea of a church as a meeting place for Christians.”3

The planning consistently interpreted the new participatory liturgy. A broad nave was to bring the congregation closer to the sanctuary. The sanctuary itself was freestanding within the overall volume, and defined by a change in level and surface material. The three key components of the sanctuary – the altar, the pulpit and the presider’s chair – were asymmetrically arranged in a dispersed arrangement intended to facilitate focus on the individual elements of the liturgy. The tabernacle was afforded its own space on a platform to the right of the sanctuary. The baptismal font was symbolically located, adjoining the entrance to the nave and also visible from the narthex. The priest’s and altar boys’ sacristies were also located at the entrance, or back, of the nave, thereby embedding processions in the commencement and close of the Mass.

A pre-narthex and narthex provided social spaces for parishioners, with views across a small shrine to the Derwent River and Mount Wellington connecting the church to its setting. A small bookshop and coffee bar were to provide places for parishioners to meet socially.

Johnston’s archive, now in the care of his son, architect Paul Johnston, contains a copy of Robert Maguire and Keith Murray’s Modern Churches of the World (1965), which features a number of churches with relatable plans and material expression using concrete block, and brick and timber construction, such as Gillespie, Kidd and Coia’s St Mary of the Angels Catholic Church, Camelon, Scotland (1961). Throughout Maguire and Murray’s book there are references to simple and vernacular material palettes.

The stark interior was a deliberate attempt to avoid the idea of the church as a monument, instead positioning it as a meeting place for the congregation.

Image: R. Farrington c. 1967, courtesy of Paul Johnston

Also relevant to the architecture of the Church of the Incarnation is the Anglican Christ College at the University of Tasmania, Hobart (1960–62), designed by Johnston’s peer, Dirk Bolt. Christ College was constructed in exposed concrete block and lauded in the state’s architectural journal, Tasmanian Architect, as “obvious, even characterless, but somehow TASMANIAN.” The article emphasized a directness in the building’s form and image, expression of structure and use of materials – the key attributes of Banham’s definition of New Brutalism – all allied to claims to a regionalism being promulgated by the journal. Moreover, the review made a religious analogy with the line “the liturgy of one’s particular architectural religion” to stress the ethic of the building’s aesthetic.4 Here was a slippage between liturgical and architectural discussions in the state, reappropriated and, more significantly, deployed to form suburban community identity through Johnston’s design.

Despite the presence of formalist elements that meant the design fell short of new brutalist ideals, the finished architecture was largely disconnected from the experiences and expectations of the congregation, and the parish’s history records a disappointment in an unfamiliar architecture, an unintended monumentality and unambiguous interiors. Those perceptions have persisted and, in the absence of heritage protection, the church has, in recent years, been painted cream and carpeted blue. However, beneath the paintwork is a rare example of an Australian brutalist church allied to postwar liturgical reform. Tasmania has a rich heritage of ecclesiastical building, including notable works by architects such as A. W. N. Pugin and Alexander North. The state’s postwar buildings, including the Church of the Incarnation, extend that heritage and deserve protection and national recognition.

– Stuart King is a senior lecturer in architectural design and history at the University of Melbourne. He is a member of the university’s Australian Centre for Architectural History, Urban and Cultural Heritage (ACAHUCH) and he undertakes research in Australian architecture.

Footnotes

1. “Private and Confidential,” Madonna, 2 October 1967.

2. Quoted in W. T. Southerwood, The Wisdom of Guilford Young (George Town, Tasmania: Stella Maris Books, 1989), 169.

3. “Sloping Floor for Lindisfarne R. C. Church,” Mercury, [undated clipping], courtesy of the Archdiocese of Hobart Archives and Heritage Collection.

4. Peter Dermoudy, “Critique: Christ College,” Tasmanian Architect, October 1962, 21.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 30 Oct 2019

Words:

Stuart King

Images:

R. Farrington c. 1967, courtesy of Paul Johnston

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2019