|

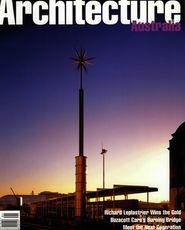

The star-topped column. Image:

|

Project Description Architect’s Note by Tony Caro The bridge has a strongly urban rather than structural expression. It was decided that a human-scaled, verandah-like link would be more worthwhile than a conventional, exo-skeletal design. Because the vicinity is visually chaotic, we developed a simple, horizontal element suggesting the pedestrian thrust. The economy of this steel structure allowed the budget to shift towards quality finishes and fine detail. The primary beam is wrapped in a zinc skin, creating a blade that spans across the Western Distributor to a monumental staircase with a lofty roof aimed at the water. Influencing this strategy was a directive that two large (5 by 3m) traffic signs were to be clipped to the bridge. While the light tracery of an expressed tensile structure would have been swamped by these signs, the monumental scale of the zinc-clad beam would not. The bridge’s relatively light deck loads are carried by outrigger beams cantilevered off the primary box girder—creating cross-sectional asymmetry which is enhanced by the tapered concrete support blades and contrast between the edge beam on the north side and the transparent south screen. The restrained architecture is balanced by a choice of rich and rugged materials— sandstone, white terrazzo, zinc, steel, glass, concrete, blackbutt decking— appropriate to both the freeway and maritime location. Because the bridge is low in relation to the CBD ridge, a vertical element (a gilded star bauble topping a stainless steel column) was installed to signal its presence to citizens uphill. Its vertical thrust is in counterpoint to the horizontality of the bridge. Comment by James Weirick The King Street Footbridge (and foreshore promenade) is among a small but critical group of recent projects which demonstrate that in Sydney, the rules of urban design have to be reinvented from first principles. Unlike the modern city’s rejection of morphology and typology or the neo-traditional city’s static reliance on both, Sydney needs a unique combination of order and disorder based upon a fixed morphology and a fluid typology. To respond to the city’s dramatic setting in a truly urbane way, the irregularities of the terrain, street patterns, boundary alignments and lot sizes have to be stabilised and pinned in space as determinants of urban form. At the same time, to respond to the dynamic quality of Sydney’s light and life, building types have to be reinvented and represented as ambiguous installations and indeterminate zones in a fixed frame of reference. King Street, the deflected cross axis of Macquarie’s Sydney, which extends from the Domain to Darling Harbour, is now terminated at both ends by pioneer investigations of this approach to ‘Sydney urbanism’: the layered installation of gallery/museum/memorial (Tonkin Zulaikha with Peter Emmett, 1994) which has colonised the geometric regularities of Greenway’s Barracks; and the fusion of architecture/furniture/infrastructure which has animated the rectilinear frame of the Buzacott Caro footbridge. As a modernist composition of pure form in space, the latter work has been extruded from the building canyon of King Street to reconnect the city and the water in a new but familiar way, like the shed/structure of a traditional finger wharf. In colonial Sydney, the finger wharves which stood at the foot of King Street were used by sailing vessels and steamers of the local trade. With the decline of coastal shipping after World War II, the collection of piers and sheds along the city side of Darling Harbour were progressively replaced with longshore wharves on landfill as part of a massive but mistaken plan to create a container port next to the CBD. At the same time, King Street was cut off from the water’s edge by the Western Distributor and a high level ramp from the Northwestern Expressway. In the 1980s, a line projected from King Street became the property boundary between the declining activities of the working port and the billion dollar theme park created by the Darling Harbour Authority on the model of Baltimore’s inner harbour, complete with an aquarium and a maritime museum on gateway sites. In a characteristic move, the back-of-house operations of the aquarium were backed onto the city below King Street. After years of neglect, the people of Sydney began to rediscover this part of the harbour when the adjoining cargo wharf was converted to a passenger terminal for South Pacific cruise ships in the 1990s. These were the site conditions for the King Street footbridge when design studies began in 1996 with the aim of creating a new link between the CBD and the waterfront. Taking off from a surreal sliver of urban space between the Royal George Hotel on Sussex Street and the concrete crash barriers of the freeway ramp, the bridge was planned to replace a little-used lower level structure and provide connections to a new wharf on Darling Harbour. The project consisted of a threshold platform on Sussex Street, the bridge itself (crossing eight lanes of traffic) with an elevator for disabled access, a walkway to the water between the aquarium service zone and the overseas passenger terminal, together with a boardwalk and shaded seating at the water’s edge extending to the Darling Harbour ferry wharf. The bridge is the central element—and the key design move was to build it as a long, verandah-like room attached to a plated box girder instead of repeating the Darling Harbour formula of an open pedestrian deck suspended in space from an ‘exoskeleton’ structure. In this way, the bridge became an understated work of architecture rather than a bravura exercise in structural steelwork. With concrete stanchions irregularly spaced on the available median strips, the box girder spans the multi-lane freeway and adjoining service roads to carry the pedestrian walkway at the level of Sussex Street to the head of a triple flight of stairs which descend to the harbour promenade. Clad in zinc to form a rectilinear blade above the city traffic, the girder carries freeway direction signs on its north face. The pedestrian deck is cantilevered on outrigger beams from its south side. The relative economy of the structural system has permitted a concentration upon highly considered detailing and elegant materials. At human scale, the bridge takes on the tactile quality and resonance of a special piece of furniture. Protected from the elements by a continuous roof, the deck flooring is blackbutt with the quality of a sprung and polished dance floor. Reverberence from every footstep fills the space with a human aura above the roar of the traffic below. On the north side, slit windows in horizontal strips are cut into the zinc skin at head height with deep reveals and sloping sills to frame and edit the otherwise overwhelming presence of traffic on the Western Distributor sweeping down from the harbour bridge. Thus protected from the north, the walkway opens dramatically to the south with a sequence of full-height views through glass—the spectacle of Darling Harbour is contained by a Mondrian-like composition of verticals and horizontals set up by the roof supports. At the western end, these supports carry the roof high above the stairway in a triumphant canopy. The stairway is faced with sandstone, a slice of artificial terrain whose artificiality is emphasised by a continuous coping in white terrazzo. This sparkles in the sun along with the high-gloss finish on the white-painted roof supports, steel poles set against the matte grey of the zinc in a minimal reference to Darling Harbour’s over-supply of white steel architecture. The single high-tech element, the lift shaft clad in sandstone, glass and stainless steel, is pulled back from the deck of the bridge as a freestanding element in celebration of its machine precision. Beyond the bridge, the foreshore works include blade walls along the promenade to screen the back end of the aquarium from view, an expanse of brick paving laid in panels and lined with the ubiquitous Ficus hillii in a valiant attempt to do something with the DHA’s landscape palette, and a highly successful slatted screen and pergola along the boardwalk which casts appropriate shadow patterns over the fake authenticity of the bollards and capstans on the brand new wharf. These works have created a whole new harbour experience, but the great achievement is the bridge—in its own right as a work of architecture, but particularly as a work of urban design. Although its design language is modernist and minimalist in a familiar way, the real value of this work resides in its re-interpretation of the rationalism proclaimed so long ago by Aldo Rossi in The Architecture of the City. In formal terms, this tradition has always been concerned with pure geometry, abstracted as a constant through a rigorous analysis of the contingencies and imperfections of the everyday world. Embedded in the morphology of the city, there is a set of pure forms—deflected, distorted, eroded though they may be. The critical urban project reveals the deep structure of the city and, in a considered departure from ‘pure’ form, isolates the variables, the contingencies and the imperfections which are susceptible to change. The footbridge is extruded from Sydney’s street pattern and terrain: the conditions of King Street’s descent on a skewed alignment to Sussex Street from the York Street ridge. The work is serious and frankly polemical, but far from doctrinaire—a mast crowned with a ‘gilded bauble’ rises above its repertoire of rationalist forms to signal its presence in the city. The bridge is pragmatically angled to conform to the property boundary of the DHA. There are water views from King Street (despite David Chesterman’s claims of blockage in AA ‘Letters’ November/December 1998). Most views were blocked years ago by the MSB shed on Wharf 10, now the overseas passenger terminal. The long line of the bridge roof, aimed straight at the water, actually draws attention to Darling Harbour while mediating the presence of the strange collection of ships. Climbing the steps to the bridge from the harbour, there are dramatic views back to the CBD … the buildings of King Street are experienced in a dynamic sequence of new vistas, with the MLC Tower as the centrepiece. The oblique alignment of the bridge and the views it generates have a profound significance—not just in scenographic terms but as a means of judging the city’s design quality. By stepping into a structure of indeterminate type—part bridge, part room, part verandah, part viewfinder—preconceptions have to be abandoned. By framing and selecting urban vistas through the movement of the body in space, critical faculties are engaged. By setting the external scene against the cool rationalism of the ‘frame’, a scale of values is established. And not much measures up. The free-for-all spread of standard building types across the city has overwhelmed the harbour setting and the historic street pattern. There is a need for a new ‘Sydney urbanism’—and the Buzacott Caro footbridge points the way. However, just as it was finished, this highly considered work was threatened with demolition. A plan by Jackson Teece Chesterman & Willis proposed the extension of King Street across Sussex Street as part of a new grid on the ‘brownfields’ site of the obsolete container port. The footbridge stands in the way of this idea as interpreted by Cox Richardson with Crone Associates. Fortunately, demolition seems to be in abeyance, as the NSW Government has announced an east-west tunnel under the CBD which will involve extensive redesign of the Western Distributor. The opportunity this presents to redesign the whole western edge of the city is so sensational that it just has to be thrown open to international competition. In generating the brief—to establish ‘Sydney urbanism’ on a convincing scale—this footbridge will be an essential point of reference. To walk across it is to experience the quality of a design language generated from a deep understanding of the city and its setting—and the exhilaration of an idea … simple, understated but beyond category. |

Credits

- Project

- King Street Pedestrian Link, Sydney

- Architect

-

Buzacott Caro

- Project Team

- Tony Caro, Stephen Buzacott, Nick Sissons, Paul Ocolisan, Clare Carter

- Consultants

-

Bridge structural and services engineers

Hyder Consulting

Builder LFC Contracting

Electrical engineer Quiggin Cook & Associates

Hydraulic consultant Patterson Britton & Partners

Landscape architect Spackman + Mossop

Project manager Farrell Projects

Quantity surveyor Cost Management Services

Structural and civil engineer Patterson Britton & Partners

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

- Client

-

Client name

Darling Harbour Authority of NSW

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jan 1999

Words:

James Weirick

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 1999