Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro elevate and reclaim the mundane. In a recent work, Drunken Clarity (2011), broken bottles of beer are painstakingly pieced together by a “weld” of gold and lacquer, like a cloisonné in reverse. Like poets at a suburban barbecue, the artists stand a little apart from everybody else. Where they find beauty and interest they also find points of critique and rupture.

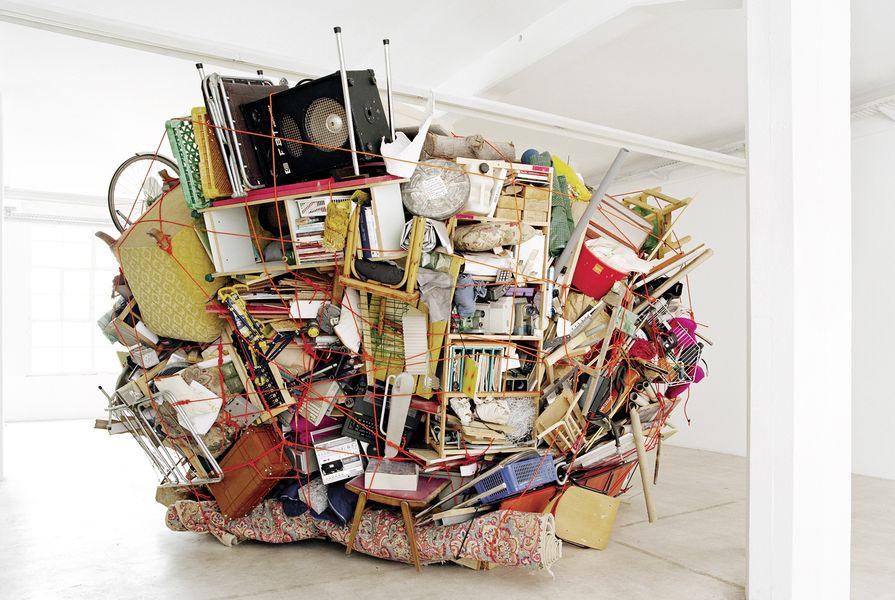

Two installations shown in photographs in a recent survey of the duo’s work, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, represent their most serious forays into the architectural and the home: Cordial Home Project (2003) and Not Under My Roof (2008). The Cordial Home Project is a large neat pile of building material made from one demolished suburban cottage requisitioned by Healy and Cordeiro on the proviso they would take the material away. The material was taken to Sydney’s Artspace gallery.

Cordial Home Project, 2003. A large, neat pile of building material has been made from one demolished suburban cottage.

Image: LIz Ham. Courtesy the artists and MCA

Unlike the celebration of built material seen in Tony Cragg’s Stack (1975), this pile is particular and tells a singular history. If the old home is now demolished but reassembled, what has been lost in its transformation into installation? Cordial Home Project examines the differences between mere material, spatial and geographic siting, architecture and the ineffable lived experience of the “home.”

Not Under My Roof, 2009. A whole floor plate from a Queensland farmhouse is transformed into a painting made up of various floor patterns.

Image: Courtesy the artists and MCA

In Not Under My Roof, a whole floor plate from a farmhouse in Millmerran, Queensland is transferred onto the wall of the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in Brisbane. It is both material and idea: an architectural plan (though 1:1) and an archive; a painting made up of various linoleum floor patterns and the house itself. As with a Vuillard or a Bonnard, we are directly asked to respond to the symbolism of the home. Like an abstract painting, Not Under My Roof threatens to engulf us and to come off the wall, swallowing us up with the weight of its own history and material.

The survey, curated by Anna Davis, carefully teases out the social histories and narratives of the material on display, in line with a critical approach to capitalism and its effects on the public and private spheres. In a show that so openly asks for the symbolism of the house to be read and restudied, the singular (and negative) reading of IKEA in the work I Hope Tomorrow is Just Like Today (2008) does not ring true.

I Hope Tomorrow is Just Like Today, 2008. In this work, IKEA furniture is arranged “like an oversized Mondrian.”

Image: Courtesy the artists and MCA

In the work, IKEA furniture becomes an abstract ground for a Pioneer plaque, one of the line drawings made for the Pioneer spacecraft in the 1970s to carry out into deep space in case extraterrestrials wanted to know about us. The artists suggested: “When the Pioneer was launched there was an ideal quest for progress, a time where there was desire for the new, a society that was concerned with change and encouragement for advancement. Now we are living in a time where the notion to seek for change has become obsolete, there is a longing to hang onto a status quo, a universal sameness [represented by IKEA].”

However, on the wall, like an oversized Mondrian, made up of the modernist primary colours, the connection of IKEA to De Stijl or Bauhaus tenets is clear. When the young Ingvar Kamprad popularized the flatpack his drive may have been utopian and democratic. The designer Terence Conran concedes that “in its way, IKEA is the modernist dream come true.”

Future Remnant, 2011. The fossil of a dinosaur is placed against IKEA furniture — “the uncertain present and future versus the known past.”

Image: Courtesy the artists and Nature Morte, Berlin

So, for example, when IKEA furniture is placed against the fossil of a dinosaur in Future Remnant (2011) the artists suggest: “The mighty dinosaur highlights the contemporary disposable, mass produced against an historical artefact: the uncertain present and future versus the known past.”

Again, it is not clear if this reading is self-evident. The dinosaur, as W. J. T. Mitchell has suggested, is the totem animal of modernity: it is mighty but also extinct, monstrous but also fallible, scientific but deeply culturally embedded, both Barney and the fossil. In this work it is not clear whether IKEA comes out as the weaker counterpart, nor even the one with the shorter history. With due respect to the artists, IKEA is complex, modern and postmodern, hopeful, fun and utopian, as well as an entity that tyrannically binds us to their Allen key.

The survey show is packed with many material goodies that all ask for close reading, both metaphorically and materially, and idealistically and politically. The show is at its best if we make few assumptions. It suggests a process of relooking at our built environments and the human psychological and cultural baggage that hangs on them. Is it up to designers and architects to show how these deconstructions and redefinitions cahopefulness and vigour?

Source

Discussion

Published online: 12 Apr 2013

Words:

Oliver Watts

Images:

Christian Schnur. Courtesy the artists and MCA,

Courtesy the artists and MCA,

Courtesy the artists and Nature Morte, Berlin,

LIz Ham. Courtesy the artists and MCA,

Ryuchi Maruo. Courtesy the artists and MCA

Issue

Houses, February 2013