The work of architects and others collaborating with one another, and the outcomes of these collaborations, are well documented in the project reviews and dossier in the Collectives and Collaborations issue of Architecture Australia. But how does collaboration benefit those who commission the buildings? And in turn, how does it benefit the public?

As our cities continue to grow and develop, the complexities of these environments will become greater and the need for collaboration will also increase. According to Queensland’s newly appointed government architect Leah Lang, “Cities are the most complex things we have on earth and we need to understand them, we need to get the balance right.” Lang will be overseeing the urban development of the state as it heads towards the 2032 Olympic Games to be held in Brisbane. “A lot of the [facilities] will be within existing urban frameworks and neighbourhoods. These buildings will be around for 70 years – they have to give back to the state and showcase what we want to be.”

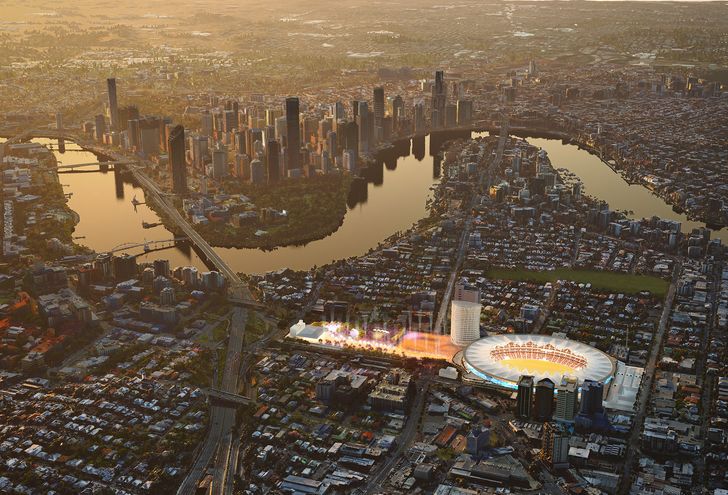

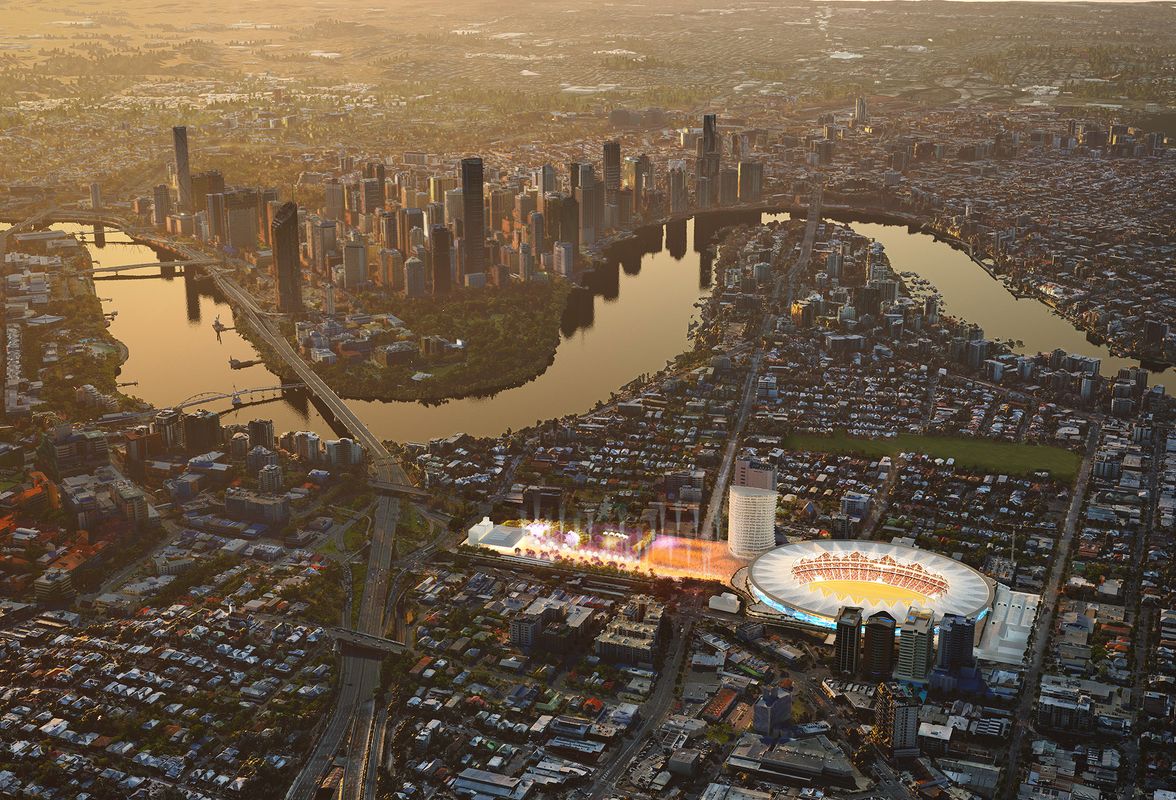

Concept plan for the redevelopment of the Gabba stadium by Populous.

Image: Populous

Lang said that for complex projects in complex settings, architects need to team up to optimize the outcomes. “When you’re talking about the complexities of stadiums or athletes’ villages, or whether it’s hospitals or schools, some firms have narrowed their typology to be subject matter experts. They are so good and so knowledgeable – doing international best practice. We need the right people at the table, who have a proven track record, but we also need to enhance it with contextual experts who know the area very well, to embed the buildings into the neighbourhoods. That’s where the government architect – whether that’s local or state – can make sure they get the perfect consultant team. I look at my role as a curator or a facilitator.”

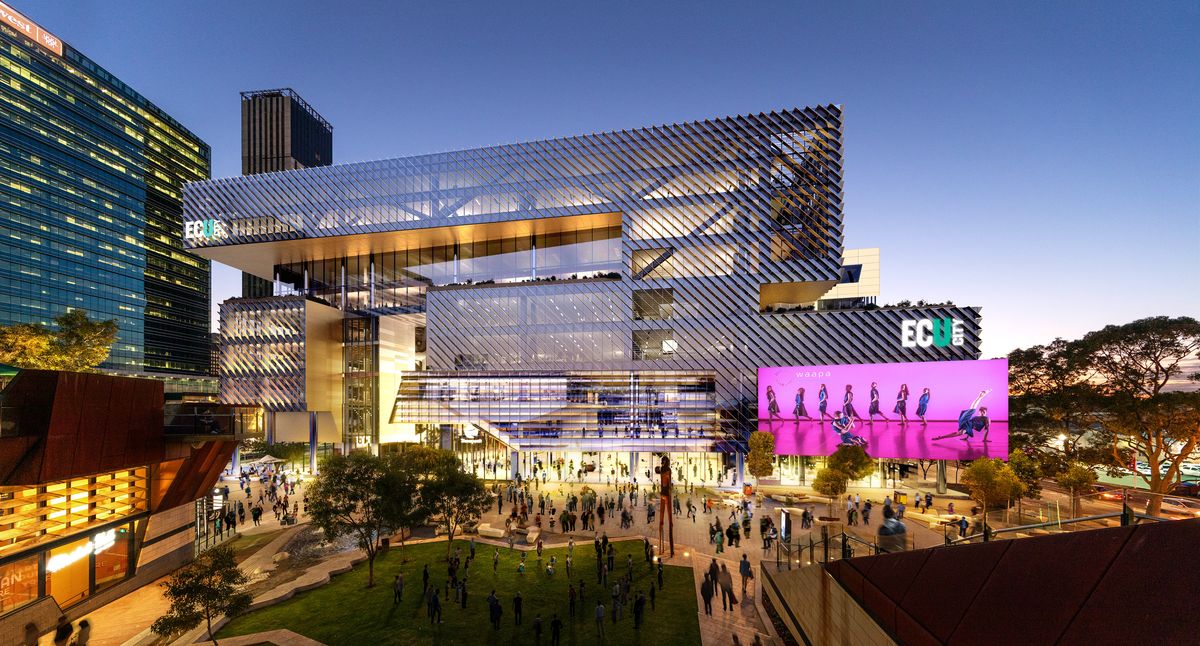

Complexity is not exclusive to government projects. Edith Cowan University’s new Perth CBD campus, designed by Lyons, Silver Thomas Hanley and UK firm Haworth Tompkins, will be the university’s base for creative industries, business and technology, as well as the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA). According to Edith Cowan University (ECU) program director Sean Henriques, who is responsible for the project’s planning and delivery, the $695 million campus will be a “game changer” for the city. Due to open in 2025, it will take the form of an 11-storey building with stacked performance spaces, studios and digital labs.

Edith Cowan University’s new city campus – a design collaboration between Lyons, Silver Thomas Hanley, and Haworth Tompkins – is intended to be a “game changer” for Perth.

Image: Courtesy ECU

ECU didn’t set out to engage a consortium through its tender process for a lead architect but, simply by the nature of its brief, the complexity and the uniqueness of the project drew interest from multiple groups of architects working in collaboration.

“We had a number of groups across all disciplines that took a consortium approach to their bids,” Henriques said. “The one consistent theme was having national, international and local partnerships involved – big and small – and they varied in terms of their individual composition. The thing that stood out with the Lyons consortium was the mix of skills between them. We felt that they were very complementary but, individually, they also had extensive experience in particular disciplines and sectors that were really relevant to what we were trying to achieve.

“This is an incredibly complex project. We didn’t want to just replicate what we do now and re-create it some-where else; we specifically wanted the architects to really push us in terms of creativity and thinking. So it was very important for us to get that diversity and range of thinking into the process. The architects are constantly challenging themselves as well. I get the impression that they’re never quite stopping or resting on their laurels. There’s always someb o dy coming in with a view that is upping the ante, which I think has been really good.”

AMP Capital’s $1 billion Quay Quarter precinct in Sydney has also benefited from a diversity of architectural contributions – particularly the residential development portion, where four practices have created a distinct collection of buildings. AMP Capital head of development Murray Middleton explained, “The project came as a result of, firstly, planning innovation. Through a consultative process with the City of Sydney, it was agreed that we could transfer floor space between the two city blocks [that we controlled] in exchange for the delivery of a series of public benefits, which involved the re-establishment and pedestrianization of an urban laneway network, reinvigoration of heritage assets, and the delivery of a precinct-wide public art program.”

Quay Quarter tower by 3XN and BVN.

Image: Courtesy AMP Capital

This allowed the development of a 49-storey office tower by Danish practice 3XN, alongside BVN as executive architect, and a residential precinct with four buildings. AMP Capital worked with the City of Sydney to choose four smaller practices to design these buildings: Studio Bright (then Make Architecture), Silvester Fuller, Carter Williamson and SJB, which, being more established, took a leadership role among the group.

“On the residential development, if you think about the brief and being in this historic part of the city, you’re really re-creating a piece of urban fabric. It’s part of a city jigsaw,” Middleton said. “The brief was to create these new buildings but give the strong sense that they had always been there, and I think it would have been very difficult to do that with one architect.

“There were regular workshops – it was a highly creative process. They actually became quite competitive in some respects, because the architects would see each other’s ideas, which kind of worked as inspiration for them to go away and innovate even more. It just added to that natural diversity that you would expect in a city that has grown organically. That collaboration contributed significantly to the organic feel and that’s what we were trying to do.”

2-10 Lotus Street mixed use building in Quay Quarter designed by Studio Bright (then Make Architecture, left) and 16-20 Lotus Street by Silvester Fuller.

Image: Courtesy AMP Capital

Lang said she is keen to adopt a similar approach to the City of Sydney in creating opportunities for emerging practices to partner with more established ones. “I love the idea of succession, of strengthening the state to make sure that we’re not just keeping these firms that are only ever embedding the knowledge within themselves; that we’re actually bringing up new firms to ensure that we’ve got this knowledge-rich state for design. And most practices that I see are very happy to do that because they also see the next generation coming through. It gives them energy and ideas to look at projects in different ways.

“I would love to see policy that encourages innovation, especially in our social housing and that missing middle component and our neighbourhood centres, community halls – all of that stuff that people interact with every day. How do we incentivize that to be better?

“Architects collaborating can become a setting for innovation. No firm is an expert in everything, and when it comes to urban design, that’s not really ever any one profession; that’s multiple sectors working together.”

When architects collaborate, they have an increased capacity to resolve complexities; they bring complementary skills and diversity in thinking; and they experience competitive team dynamics, which ultimately lead to innovation. All these qualities benefit their clients. But what about the risks of having too many architects on the team? Do too many cooks spoil the broth?

“You could almost argue that [the collaboration] has made it less risky,” said Henriques. “We’ve adopted a very transparent and concerted process, aimed at keeping everyone in the tent. In a design sense, we’ve worked really closely with the Office of the Government Architect and the State Design Review Panel, and made that a genuinely interactive and collaborative process. The process of refining the design has mitigated risk.”

Middleton admitted that the collaborative nature of Quay Quarter made it more difficult for his team. “There was more work involved to get to the point where we typically offload the risk to a design- and-construct builder.” But, he explained , in this regard, the risk profile was no different to a typical project. “We had advanced the design sufficiently to have comfort that, upon novation, that design would be de- livered. Because of the tight relationship between BVN and 3XN, when we novated it, we novated BVN to the builder, and we retained 3XN in more of an oversight role. We had confidence that BVN – because of the journey they had been on with 3XN – were committed to delivering the more detailed documentation.

“And on the other block, where we had four architects – it was more work for the builder, but that was the nature of the project.

“At the end of the day, the outcome is more important to us. If we can provide a better outcome for our customers and our owners, it leads to not only a more risk- free approach, because we’re developing a solution that is going to achieve greater market acceptance, but it’s going to be better in terms of both short- and long- term returns. So even if we go through a more rigorous process, and it’s more work to achieve it, that’s in many ways a small price to pay.”

Source

Discussion

Published online: 24 Feb 2022

Words:

Linda Cheng

Images:

Courtesy AMP Capital,

Courtesy ECU,

Populous

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2022