The city is in a state of flux. The visionary, top-down masterplanning approaches of the 20th century delivered an urban infrastructure ill-equipped for the indeterminacy we face today. Resource limitations, mass migration, austerity measures, housing crises, insecure work conditions and rising inequality have defined the beginning of the 21st century. Amidst this context, the “sharing economy” emerged, promising radical, dynamic solutions for reprogramming the city, increasing access to existing infrastructure on an as-needed basis. Platforms like Airbnb, Uber, Splacer and Task Rabbit are facilitating commercial peer-to-peer sharing of everyday resources and skills. On an urban level, these platforms have enabled flexible, temporary access to privately owned space, which in theory intensifies use and maximizes efficiency. In this way, Airbnb and platforms like it can perform a similar urban function to the “pop-up” or the interim-use place activator. Projects like Marcus Westbury’s Renew Newcastle are based on these principles.

In practice, however, the current lack of regulation means that sharing is not always peer-to-peer. An entire industry of professionals has emerged to service individuals and companies with large Airbnb property portfolios, and the repurposing of residential infrastructure exclusively for short-term holiday rental has been criticized for having the reverse effect: reducing available housing stock, accelerating gentrification and lowering occupancy rates, with properties sitting vacant for long periods of time (independent, open-source data tool Inside Airbnb shows that on average, occupancy rates for “entire house” listings (4,778) in Melbourne in January 2016 were estimated to sit at 22.6 percent).

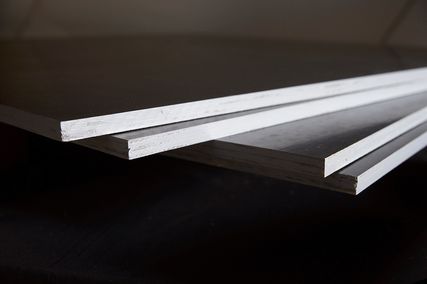

The Occupied exhibition at the RMIT Design Hub, which included ideas for housing more with less, retrofitting, adapting and repurposing existing structures and environments. Exhibition design by Otherothers.

Image: Tobias Titz

The opportunities and dangers that the sharing economy presents for architecture and the city have been the subject of speculation at a number of major exhibitions this year. Locally, RMIT Design Hub’s Occupied (curated by David Neustein, Grace Mortock and Fleur Watson) explored a variety of solutions to resource limitations, including my own experiment into the utility of Airbnb-as-activator: the Supershared loft, created in collaboration with Sibling Architecture. The loft was a bookable, nested space within the gallery, simultaneously listed on a number of different peer-to-peer online platforms to test the intensification of space through the sharing economy. Each platform promoted a particular kind of occupation (living, working, making, doing or storing) and operated on different increments of time (from one hour to six weeks). By providing a private but visually permeable space to occupy throughout the exhibition, adjacent to the curated works and sanctioned program, Supershared investigated the increasingly muddy relationship between public and private space in the digital age.

The blurring of public and private realms, and the voyeurism associated with “living like a local,” is the subject of Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine’s recent film Selling Dreams, launched at the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale: After Belonging. At the same event, OMA launched Panda, a “counter-organizational” digital platform arming individuals against the current “oppressive” insecure work practices of the gig economy. And in Venice this year, the exhibition in the British pavilion curated by Jack Self, Shumi Bose and Finn Williams, Home Economics, explores the commodification of home, envisaging a nomadic future for residents in response to the current housing affordability crisis – proposing a home for hours, days, months, years or decades. But architects are not alone in their investigation of the accelerating influence of digital platforms on the dynamics of space. In August, Airbnb weighed in on the conversation with the announcement of Samara, an in-house design studio, the mission of which is dedicated to envisaging new futures – but for the company. Airbnb’s founders have been explicit about their intention to diversify the company’s operations to safeguard themselves against competitors.

Airbnb’s in-house design studio Samara collaborated with Go Hasegawa to create a community centre for the local community in Yoshino, Japan, as part of Kenya Hara’s 2016 House Vision exhibition.

Image: Edward Caruso, courtesy Samara

Despite its origins as part of a business plan, Samara’s first project for the shrinking Japanese town of Yoshino is a worthy experiment. The ageing population in Japan, combined with the increasing migration of the younger population to larger cities, has left many rural towns devastated. For the 2016 House Vision exhibition, curated by Kenya Hara, Airbnb has partnered with architect Go Hasegawa to develop a new community centre to service locals and tourists, with short-term accommodation available upstairs, in an effort to encourage tourism to the area and foster a culture of Airbnb-hosting among residents as a source of income. The land was donated by the city and the project was built with local labour, all of which make for a nice narrative.

The company suggests that Samara will be working towards developing new “hardware” (infrastructure) and “software” (new uses) in the future. This represents a marked shift into property development for the world’s largest accommodation provider, which until now has owned no real estate. Airbnb’s major contribution to architectural discourse to date has been about software: its ability to unlock, repurpose and intensify existing infrastructure. While there is evidence that the existence of Airbnb has already started to drive housing diversity (hardware), the idea of new developments designed to cater exclusively to an Airbnb market is generally something to avoid in urban settings: Airbnb is valued by its users for providing a more “authentic” experience, bringing tourists in closer proximity to locals, but this kind of purpose-built accommodation can have the reverse effect by creating direct competition for longer-term residential housing. Yet regional towns like Yoshino offer the ideal testing grounds for new kinds of tourism-oriented infrastructure. Dispersing the positive effects of the sharing economy is vital and, in this case, the community also benefits from use of the facilities.

The relationship between public and private program is unambiguous in the design of the community centre, which aims to bring guests and locals closer together. But given the established culture of temporary rental of public infrastructure for private use in Japan, the decision to launch Samara there is likely to be strategic. Manga cafes, love hotels and karaoke bars exemplify the concept of “dividual space” (a term coined by Jorge Almazán Caballero and Atelier Bow Wow co-founder Yoshiharu Tsukamoto in 2006) where guests can obtain immediate, cheap access to public “rooms” for unrestricted private use for short periods of time. Sound familiar? This culture has developed as a result of citizens making use of the city for activities traditionally related to the home in response to space limitations, preempting the sharing economy ethos that you can own less and enjoy more if you share.

The contribution that Airbnb can make to intensifying latent urban sites has been well-documented. Airbnb has extended this logic to regional contexts, and coupled with Hasegawa’s sensitive, vernacular approach, its first sizable architectural project feels like a tentative toe in the water. However, the suggestion that Samara is also intended to launch the company into urban planning has much larger and more concrete implications. Airbnb is valuable precisely because it provides the spontaneity, dexterity and incrementality that is missing from planned environments. The idea of global corporations like Airbnb embarking on large-scale urban schema is unnerving, and contradictory to the circumstances that first gave rise to the sharing economy. If the company wants to contribute to better cities in the future, it might begin by paying city taxes, leaving the strategic planning to local experts, who can direct the disruption to minimize damage and maximize opportunities according to the local context.