A SMALL PUBLIC BUILDING BY DIMASE ARCHITECTS. REVIEW BY URSULA DE JONG.

PHOTOGRAPHY YVONNE QUMI

Review

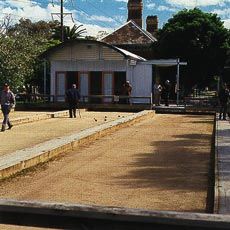

SPRING IN MELBOURNE is unpredictable. But come one o’clock on a Sunday afternoon the Montemurro Bocce Club members gather at the North Carlton Bocce rink.

The games are underway. Concentration. Dispute. Measuring tapes are out. A decision is clear. The competition begins again. Compromise. Reconfiguring. Discussion. Dialogue and the game continues. Bocce or architecture?

Most of the club members come from Montemurro, a small hillside village in Basilicata, an isolated part of Italy, about 100 kilometres east of Naples. They are all emigrants who arrived after World War II in the early to mid 1950s. Since the new facilities have opened, the members have had lots of visitors and many questions about the aims and rules governing bocce. They enjoy their new facilities but cannot understand what the fuss is about.

The Bocce Pavilion, by dimase architects, is a small municipal project that forms part of the North Carlton Railway Station Neighbourhood House. It is a community facility and the Montemurro Bocce Club is not the sole user.

This modest pavilion invites closer scrutiny. It is interesting in terms of the significant effects that “small a” architecture can have within communities and it raises issues of contemporary architecture in relation to heritage buildings and planning controls. It is also a very beautifully designed and detailed building which provides a level of improvement and enrichment to the neighbourhood beyond what was asked for.

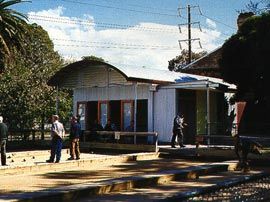

The project’s gestation was long and drawn out. The bocce rinks were originally located in Princes Park. In the mid 1980s, in conjunction with the Melbourne City Council, a neighbourhood house was established at the disused railway station in North Carlton. A toilet block (designed by MCC) was built as part of the conversion. This was a companion building to the railway station – curved roof, slab on ground and Custom Orb cladding. It was small, separate and discrete. Five years ago Antony di Mase, of dimase architects, was approached to separate the Bocce Club from the neighbourhood house, as there was a conflict between the functions of the two groups. Di Mase took on the toilet block: rather than design a competing form, he designed the new pavilion to take its cue from the scale and proportions of the existing amenity block. From the south the differences are subtle. The main approach is from the north – from the old railway platform or from the gardens of the linear park.

Much thought went into the design of this crafted “object”, its place in the landscape and its connection to the existing building, into creating an identity and a presence.

But funding was not forthcoming. Finally, the City of Yarra and the Department of Sport and Recreation made funds available in 2000. Planning took an eternity. Heritage advice prevented any encroachment beyond the original railway station alignment. The difficulty was how to turn a railway station into a community facility. How much of the late nineteenth-century polychrome brick station could/should be retained without compromising its current and future functions? A commonsense appraisal of the heritage issues had to be made in order to realise the potential of the contemporary design. Eventually 1.3 metres were gained, with dimase architects arguing that the new facility required its own sense of entry and identity. Then the Open Space Department required the retention of a large established pittosporum tree. This compromised the pathway, and hence the journey, from the railway platform to the new pavilion, by creating an awkward physical break. Dimase architects then redesigned the northern entry into a triangulated portico.

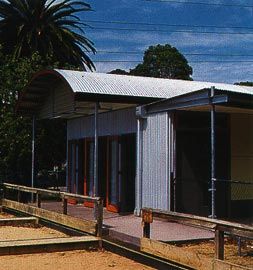

Today one is greeted by the triangulated portico, supported on one column and aligned with the railway verandah columns. This skin-and-bones architecture is connected to, yet different from, the existing building. Inexpensive materials – coloured concrete, galvanised steel, Custom Orb, timber windows, linoleum – are used well. A blank wall invites shadow play, a threshold and door invite entry. The box gutter becomes an internal bulkhead that gives greater definition to the entry. Carefully placed windows connect the interior to the original railway platform, the bocce rinks and the canopy of trees on the south side.

Sensitivity to and awareness of site is paramount. Changes in colour lead one in, and further connect inside and outside. The blue curved ceiling creates a soft “sky” effect. There is a far-off reference to de Chirico’s paintings – empty piazzas, strong light and shadows, distinct but subtle colours, echoes of arcades going nowhere, stillness – and to a kind of monumentality found in Rossi’s Teatro del Mondo – lightweight, floating, yet permanent.

The eastern elevation – the front of the pavilion – creates pictures at every given distance, just as Ruskin called for in the nineteenth century, but here there is no historicism.

The geometries are subtle: the curve of the pavilion roof sits below the eaves of the hipped slate roof of the railway station, topped by the heavily massed chimneys of a bygone era.

The contrast in materials, massing, colour and craftsmanship is pleasing. Ideologies of the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries co-exist. Both buildings rely on good proportion and composition for effect. The Bocce Pavilion easily allows for the presence of the other. On this eastern elevation, the pavilion is asymmetrical. The geometry changes as the doors open to la verandah – as the club members call the sheltered transitional space. In the morning sunlight the screen in the gable casts shadows onto the Custom Orb. The whole is human in scale, almost domestic, unpretentious.

This small Bocce Pavilion offers a comfortable “no fuss” place for the community. It can be appreciated as a crafted object in the landscape of the linear park. It looks well from a distance and functions on a practical level. It has a real presence and creates a sense of place. For the community it raises the issues of contemporary architecture in relation to heritage, challenging the prescriptive “neighbourhood character” planning regulations and introducing a new language of architecture in a non-confronting way. It is only by inserting such beautifully designed and detailed buildings into the public realm that attitudes to contemporary architecture will change.

Dr Ursula de Jong is a senior lecturer in art and architectural history at Deakin University.

Project Credits

MONTEMURRO BOCCE CLUB PAVILION

Architect dimase architects. Builder DJO Constructions. Engineer Maurice Farrugia + Associates. Building Surveyor Yarra Building Services. Client City of Yarra.