Three concurrent competitions aim to remake the heart of the University of Sydney. Philip Drew reviews the outcomes and speculates on the future.

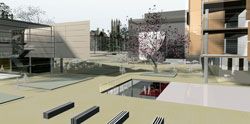

Concept image of the winning entry for the USYD Central competition by John Wardle Architects in association with Wilson Architects and GHD.

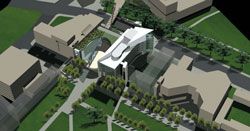

The winning entry for the Faculty of Law building by FJMT.

Shortlisted entries in the Faculty of Law competition. Donovan Hill in association with GHD and Wilson Architects.

3 x Nielsen.

Commended entry by Foster and Partners in association with Hassell.

Bligh Voller Nield.

Axel Schultes Architekten in association with Stanisic Associates.

Shortlisted entries in the USYD Central competition. Daryl Jackson Robin Dyke.

Lab Architecture Studio.

Benson and Forsyth in association with DesignInc.

“‘True, Plato isn’t very rich, though he has more than Socrates had; but the school does accept endowments. Only from Academy men; but he won’t be beholden to outsiders. Dion gave us the new library. But no one, ever, is accepted for what he owns – except here.’ He tapped his brow.” Mary Renault, The Mask of Apollo, 1996, 72.

The early sandstone buildings at the University of Sydney were located along a prominent ridge so they faced the city with nothing in front besides a grassed terrace and a long avenue leading down to City Road. Like eighteenth-century Royal Crescent at Bath, they stole what lay beyond the terrace edge. Hence, the University of Sydney was initially a counterpoint to the city and its early buildings spoke a common idiom of Gothic Revival.

Thoughtless postwar expansion blanked out the city view. Indeed, the University of Sydney has been dogged by repeated institutional memory lapses. Over its 154-year history there were plans by George McRae for the Camperdown site in 1913, Walter Burley Griffin in 1915 and Professor Leslie Wilkinson in 1920 – all to little effect. For a short while, during the inter-war period, Wilkinson was able to impose a Mediterranean-inspired style. What consistency there had been was sacrificed after World War Two to an expedient laissez-style toapproach. This resulted in a campus of unexceptional mediocrity overlaid with an air of permanent grubbiness.

In June 2003 the university instituted a two-stage international architectural competition for three projects in what the university’s vice chancellor, Professor Gavin Brown, described as the most significant development since its foundation in 1850. The aim is to “dramatically reshape and improve the quality of the campus environment”. As part of an overall masterplan for the university, the Campus 2010 programme comprises a new 60,000 square metre Faculty of Law building to cost $82 million situated behind Fisher Library stack; a 12,850 square metre integrated student services facility and science and technology library to be called USYD Central, costing $50 million, beside the Wentworth Building on City Road; and a 60,000 square metre, $13 million upgrade of the public domain of the Camperdown and Darlington campuses, encompassing Eastern Avenue from the new Law Faculty Building to the USYD Central Building and Maze Green, and including a new footbridge across City Road.

Capital Insight managed the competition process, setting up a website and establishing a design review panel comprising Professor Chris Johnson (NSW Government Architect) as chair, Professor Tom Heneghan (USydney), and Professor James Weirick (landscape, UNSW), with representation from the University of Sydney. The competition format was exceptional and deserves praise for its openness and inclusiveness. It avoided the usual secret deliberations and the open-access website supplied all information for competitors and anyone else who was interested (www.usyd.edu.au/campus2010). Presentations were held in open forums. This assisted everyone, and such a transparent process meant that no-one felt excluded.

The $150 million competition attracted 120 proposals – many from Europe (there was no interest from America or Japan). On 1 December the university Senate confirmed Francis- Jones Morehen Thorp (FJMT) as winners for the Faculty of Law building; John Wardle Architects in association with Wilson Architects and GHD for USYD Central; and joint winners Jeppe Aagaard Andersen in association with Tinka Sack and Turf Design, and Taylor Cullity Lethlean for the Public Domain. The jury also especially commended the Faculty of Law building entry by Foster and Partners in association with Hassell.

The University of Sydney sees its Campus 2010 design competition as crucial to its future. The programme is intended to remake the heart of the university. Rather than being a simple cosmetic facelift, it will integrate facilities – concentrating student services at present scattered across the campus, relocating the law faculty from its present city location onto campus, and removing cars from Eastern Avenue to a 420-space car park beneath the new Faculty of Law building.

It is, however, unclear what the jury sought in choosing winners, whether a scheme or an architect, or both. It is now apparent that the successful schemes will be modified and that considerable further work will need to be done to develop each project to meet base requirements. In part, this was inevitable and necessary in order to interweave the two new buildings into the new fabric of the public domain.

The complexity of USYD Central (the Student Services building and Science-Technology Library) offered a greater challenge than the more straightforward Law Faculty building.

Submissions for the Public Domain competition generally lacked depth – this may be because the outcomes of the two building competitions were unknown, and hence, the Public Domain designers were forced into generalities rather than specifics.

A number of schemes from the two building competitions relied on hovering slabs above a plane penetrated by circular or elliptical voids (Foster and Partners in association with Hassell, 3 x Nielsen, Axel Schultes Architekten in association with Stanisic Associates, Benson and Forsyth in association with DesignInc, Lab Architecture Studio). Schultes and Stanisic varied this in their Faculty of Law proposal with a wave-shaped void that opened on opposite sides to connect the Anderson Stuart Building through to Victoria Park. Its walls were pushed sideways towards Fisher Stack to differentiate the two halves. Foster and Partners, in spite of its recent UK law faculty experience, badly misjudged the scale in this one, and while the hovering slab was unquestionably a tour de force, the massive form was narcissistic: it established no external relationships and overwhelmed the objects around it.

To a considerable degree, such schemes are one-liners – simple strong statements but little more. In the two-stage competition process, initially brilliant presentations did not necessarily guarantee a convincing second-stage scheme. Early promise often failed to materialize and clever initial diagrams often remained just that, rather than becoming wellrounded fully fledged designs.

FJMT began with a similar monolithic slab proposal for their Faculty of Law entry, but abandoned it four to five weeks before the second-stage submission due date because it was thought to be too overwhelming and entirely out of scale. Instead of dividing a single shape, FJMT opted to build the form, through addition, from smaller units, reversing its earlier approach in what Richard Francis-Jones calls a “project of parts”. This additive mode of composing forms was more flexible and made it easy to define axes and establish view corridors, and to break down the scale to relate it better to the surrounding buildings. The developed nature of this scheme also allows sustained discussion.

FJMT’s analytical sketches tell the story: the sequence of plaza and vertical transparent gate through to Victoria Park delineates the Anderson Stuart Building axis; crossing into the park the axis fans out into a series of diagonal view corridors that allude to the 1920 Leslie Wilkinson plan. The new additive approach was crucial – without it, FJMT’s design would have been similar to the other monolithic proposals.

The creation of a transparent gate framing the Anderson Stuart axis was decisive and helped compensate for the earlier loss of the university’s visual connection to the city. The offices on the two sides of the central circulation corridor of the Law Faculty terminate on either side of this axis to expose a slim, seven-metre-wide vertebrae/bridge, which opens a large window to the city. Regardless of which side they are on, all the offices enjoy excellent views either to the Law Plaza and the Anderson Stuart facade, or to Victoria Park and the city.

FJMT first established a podium to contain the car park and teaching areas spread over four levels. Above are the three figures of the Law Library, the Moot Court and the teaching spaces arranged so they form a triangle. The teaching spaces at the rear, which connect with FJMT’s earlier Eastern Avenue Auditorium, repeat the same triangular motif; these have been combined with food and social areas which spill informally out onto the plaza. Opposite it, a stainless steel clad light tower nestles against the south back of the Fisher Stack, puncturing the podium and giving access via a ramp to the two-storey Law Library below.

The strength of FJMT’s proposal is its care in establishing a series of connections with the context. A “solar wall” facade develops a similar fine-grained and detailed expression to Anderson Stuart’s sandstone. The deep assembly of outer fixed glass skin has intermediate adjustable timber louvres between an inner, second glass skin that can be opened to admit heated air in winter or closed to vent the hot air out the top in summer. A horizontal light shelf above the opening bounces light onto the ceiling.

The USYD Central brief was more complex, housing a number of functions. The UK’s Benson and Forsyth, in association with DesignInc, integrated their architecture with the existing Wentworth Building, perhaps little realizing how hated Wentworth is. It was a thoughtful if unappreciated gesture on a campus more noted for its disregard of contextual issues – possibly a little too European under the circumstances.

John Wardle Architects’ design for USYD Central won in spite of its lack of architectural detail. A recognition, perhaps, of its handsomely sculptured bridge connection, but chiefly, one suspects, because its open frontage along City Road would flood the plaza with sunlight.

Building on this, glass facades below the plaza level link it to Maze Green. The integrated student services component is accommodated in a sheer tilted crystalline volume whose light airiness is enormously appealing but lacks detailed architectural definition. (The knuckleshaped sun-blockers on the glass City Road facade seem more decorative than functional.) This elusive non-building almost melts into the adjoining park.

Given that the Law Faculty and USYD Central results were unknown, the Public Domain submissions were reduced to deploying standard landscape construction details of paving, avenues of trees, water features. Compared to entries in the two building competitions, these submissions were weaker. A great play was made of sustainability when it should have been included as routine.

The exception was Jeppe Aagaard Andersen (with Tinka Sack and Turf Design): his ingenuity in offering a series of incidental discoveries, including shallow recesses that fill with water after rain to create mirrors, later drying up, thereby adding an element of the unexpected to the avenue, was rewarded with the joint first prize (along with Taylor Cullity Lethlean). But the suggested baroque water basin at University Place to terminate the Quadrangle axis is clearly a mistake – the University of Sydney, after all, is not Drottingholm, much less Versailles.

In terms of creativity, the Public Domain proposals rarely did more than scratch the surface. The Chemistry Building reduces Eastern Avenue to half its width. It would take more than black magic to repair this blunder. Kicking the cars out will give pedestrians greater security but this risks making Eastern Avenue too diffuse – a wider, less concentrated thoroughfare will reduce the number of chance encounters between people.

Scunge abounds on Sydney University campus: notices of every description, posters obliterate walls, events are chalked on stair risers and graffiti proliferates. One solution that occurs to the writer might be a system of electronic displays along Eastern Avenue to carry student ads, list events on campus, sale of textbooks, rooms to let or share, etc. Instead of its being merely a route for hurrying feet, by converting it into an information environment it would become much more useful and lively and central to student lives. A large screen on the Law Faculty plaza could show live relays of international lectures on campus or display important university announcements. Once the system was operating it could be accessed at home or viewed on monitors in Eastern Avenue.

Against a background of enormous change, with cutbacks on publicly funded places, increasing acceptance of corporate values, and the internationalization of Australian universities, the University of Sydney’s $150 million Campus 2010 programme is an admirable if overdue undertaking, but it oddly sidesteps larger strategic questions about the overall shape and character of the campus. It looks backwards more than forwards, and is more conservative than radical. Electronic information sites on Eastern Avenue, if they were incorporated, would send a quite different message about engagement with the future.

No-one can be certain what universities will be like in ten, much less fifty years hence.

The strength of universities is their tradition of independence and intellectual freedom. More than ever, they need to remain progressive, open centres of intellectual excellence and research; they must continue as inclusive and non-discriminatory centres. Our universities should be an open door to all who have the intellect and creativity to contribute and benefit from access – not unduly restrictive places of limited ambition. University architecture must express the same vision. As a city within the city, the planning and architecture of the university campus ought to demonstrate to the city at large a model of sensitive urban integration, unity and consistency and uniformly excellent architecture. The University of New South Wales, a late starter, has done much better with its unifying pedestrian axis from Anzac Parade, its covered walkways on the upper campus, integrated quadrangles, the even temper of its architecture and consistent quality landscaping. Much remains to be done at the University of Sydney, even with its Campus 2010 plan in place.