In May 2000 Prime Minister John Howard announced that, as a gesture of the Government’s commitment to the ongoing reconciliation process, it would support a reconciliation square in Canberra. The National Capital Authority and a steering committee of local Ngun(n)awal and national Aboriginal representatives then developed the Reconciliation Place Competition brief.

The prominent site, in the heart of the Capital axis, elevates the significance of Reconciliation Place as a commemorative public space. The brief specified a broad range of reconciliation objectives and a number of suggested themes. It also asked that the work consider its adjacency to the Commonwealth Place site and be sensitive to the larger framework of the Parliamentary Zone. Thirty-six entries were submitted and the jury selected seven commendations, two second place entries and one winner.

The NBC Aboriginal Corporation, one of the second place winners, proposed an event where “communities gather and work together for the future…. listening, talking, laughing, creating, story telling, knowledge sharing”. This involves “free flowing” spaces spread across the landscape with no pre-determined outcomes. The designers assert that “reconciliation is a process not a product… an activity not a memorial”. While these intentions are inspirational, they remain in the realm of ideas. To realise this entry one would first have to define “community” – who participates, who doesn’t, who gets priority and so on. Given that anything built within the Parliamentary Zone has to be approved by Parliament, the unfortunate answer is whomever the Federal Parliament felt was appropriate. Even if an equitable method of choosing “community” was discovered, who determines what materials are then selected, which forms are created, and what happens when the unavoidable staking out of turf via cultural interest groups occurs? It could be an interesting process of negotiation at best, a repeat of dispossessing those who hold less power at worst. However, by denying pre-determined form, the design makes a statement about flexibility in the rules we set for ourselves. Perhaps the greatest strength of this response is the openness which allows any number of things to occur.

The other second place scheme, by Taylor Cullity and Lethlean, consists of layers of landscape allegories. Organised through four metaphors – the Healing Stone, Paths of Rediscovery, the Sea of Reconciliation, and the Field of Hope – this plan-generated project navigates the visitor through a series of thematic spaces. Entering from the east or west, one encounters a framework of locating markers which denote the 390 Aboriginal Australian regions or language groups. A map assists visitors to find their own “path of rediscovery” by discovering the Aboriginal land on which they live. The markers take on solid form only when reconciliation is acknowledged by the Indigenous people of the particular region.

But just how does a community decide it has been reconciled? The Healing Stone, described as both wound and scar, is a very long linear stone axis that can be used as a bench. Water (a metaphor for blood) and recorded voices of Aboriginal Australians (in both English and their native languages) flow from its centre. Finally, the Field of Hope occupies the centre of the site.

Dedicated to the local Ngun(n)awal people, it is described as “outstretched mounds reaching out to touch each other”. Within the cavity created by the earthworks are local native seedlings planted by visitors and a ceremonial fire in the centre of the axis.

This scheme relies on expectations about how people participate and understand landscape gestures. Yet there is no complex investigation of the way different cultures read symbols and metaphors. The strength of this proposal is that it calls for rituals and interaction – a participatory outcome which could engage the nation. But the forms and metaphors seem to rely too heavily on a literal interpretation of reconciliation.

The most striking aspect of the winning entry, by Simon Kringas and colleagues, is its scale. A very large promenade connects the National Library and National Gallery. Its geometry is part of the existing formal framework of the Parliamentary Triangle.

Vertical slivers are strewn along the promenade which rises subtly to a mound at the central axis of Commonwealth Place.

Paths through the slivers offer multiple readings and multiple journeys. There is no singular way through. The slivers seem almost random, but strategic in the way they respond to adjacent buildings. They are added over time – as reconciliation occurs it can be reflected in the landscape. However the design does not address the critical issue of what is on the slivers, nor the process of how the information is selected.

The NCA will most likely set a series of guidelines for them. The actual procedure of sliver approval is also somewhat concerning; both Houses of the Parliament need to approve each of them. Thus, they ultimately choose which history, which text, and which image is appropriate. This is disturbing given their track record. The formal outcome of the proposition is somewhat minimal, with strong spatial consequences. It is fairly flexible in terms of how the splinters are developed and offers a critical landscape integrated into the Parliamentary Triangle fabric. However, it doesn’t necessarily participate in larger urban conversations. It seems a missed opportunity not to consider how the slivers may find their way into the tent embassy as shelters, or to the new National Museum of Australia’s Garden of Australian Dreams, or even as mundane landscape objects (bus shelters, signage, etc.) scattered throughout Canberra.

Of the seven commended proposals, two offer very interesting ways of thinking about reconciliation. Room 4.1.3/UWA’s entry offers an urban design scale gesture with a “microcosm of the land itself, something understood by and something fundamental to everyone – the earth of Australia, reconciliation’s common ground”. From Commonwealth Place to Common Ground, the proposition continues the land axis through sculpted landforms that engage with crucial views and frame a central space. This space contains soil types, collected by the community from each of Australia’s 390 regions, arranged in an east west spectrum. This proposition involves landscape metaphors, yet it is somewhat speculative and ironic in its gestures. The design allows new interpretations of the physical environment as perceived through cultural or political maps in both indigenous and non-indigenous cultures.

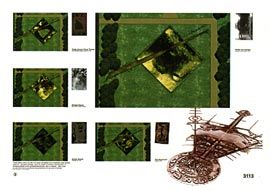

The Corrigan entry is truly innovative. A large square of indigenous grasses is bisected by a diagonally aligned path. The site is intentionally “out of alignment with the order perpetuated by the Parliamentary Triangle”. The path points at the High Courts, demanding it enact changes in legislation that will ensure acceptable representation for Aboriginal Australians. A series of large-scale images, burnt into the area, can be seen from both Parliament House and the National War Museum – two very prominent tourist destinations. The images are selected by the local Indigenous community – it is their voice in the end.

While at first glance this scheme may seem a one-off gesture, it has richness and a boldness which cannot be ignored. It allows a constant state of flux or transformation of both landscape and culture. It uses landscape processes (controlled burning, revegetation) to inform a progressive memorial gesture. The formal resolution stays true to the designers’ assertions that “Aboriginal culture is an elusive concept and resists a cohesive definition” while also negotiating an act of reconciliation.

Other agendas became evident when the winning schemes were publicised. The project was immediately rejected by the Aboriginal tent embassy as a conspiracy to undermine and eventually replace the tent embassy. Aboriginal Affairs Minister Phillip Ruddock replied that this was the intention, but that it was ultimately up to the embassy itself. In a city like Canberra where memorial objects line Anzac Parade and official memory is built for the nation to read, the tent embassy operates as a counter-memorial.

In addition to being a site of protests, the tent embassy recognises the strength and perseverance of Aboriginal culture, and demands that things must change. Thus, it seems necessary that the official Reconciliation Place must sit along side the tent embassy, offering alternative views on the reconciliation process and hope for its future. The overall strength of the intentions behind Reconciliation Place is perhaps summed up by Annabelle Pegrum, chief executive of the NCA: “Australia and its people are profoundly affected by these things. The discussions and debates which occur as a result of this process help the nation grow in its intelligence.”

SueAnne Ware is a senior lecturer in landscape architecture at RMIT University.