Romesh Goonewardene considers the recent limited competition.

The Cottesloe Surf Lifesaving Club is the oldest lifesaving club in Western Australia (founded only two years after Australia’s first, Bondi, which started in 1907). Its current premises, occupying a magnificent limestone outcrop overlooking Perth’s most civilized beach, were built in 1954 and look a little tired. In need of a new building to facilitate its fifty-year business plan, the club consulted Laurie Hegvold, long-time head of architecture and Emeritus Professor at Curtin University. He recommended a limited competition, which was lauded and supported by the local authority.

The first prize of $5,000 was presented to Spaceagency, in collaboration with mOrq. The jury, chaired by Hegvold, also commended the entry by Iredale Pedersen Hook and thanked the other two invitees, Jones Coulter Young and Donaldson + Warn, for the high standard of their submissions.

The competition is a small victory for a certain type of architecture, a global contemporary aesthetic which is the metier of a certain (young) generation of architects. The four invited firms all have identities partly invested in competition and award winning and, with one exception, have baby boomer principals overseeing gen-X and gen-Y floor staffers. IPH are cusp gen X ers. The significant thing is that the submissions represented not just each practice’s specific, considered response to the problem, but also a real-time projection of its relation to current architectural symbolic capital, which I shall briefly explain later.

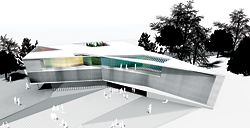

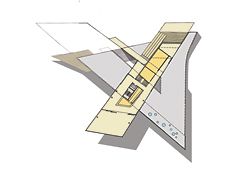

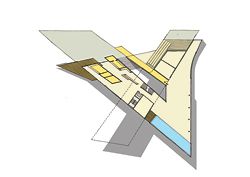

The winning scheme has a crisp geometry and sophisticated choice of materials derived from a variety of site and contextual factors, circulations, views and environmental performance. The shape and cutouts from the extruded form are derived from the morphology of the deformed tea-trees on the site, which bend backwards from the force of the wind. Importantly, the scheme is presented and looks like an international competition award winner.

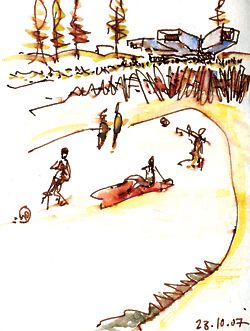

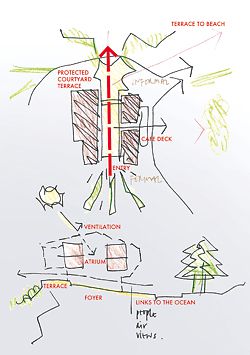

The IPH and Donaldson + Warn schemes are more modest in scale and materiality, choosing masonry and cheap panels. Donaldson + Warn took a very pragmatic approach to the problem, working with the utilitarian idiom of earlier masonry clubhouse models in Perth and then allowing it to dissemble as it ran down the slope. IPH adopted an ocarina-shaped plan, based on the idea of reversibility of views and surveillance and yielding T-shaped viewing towers. While the scheme was highly commended by the jury, I wonder if they found the towers a little menacing.

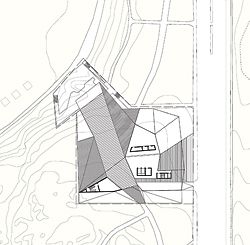

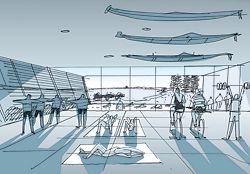

JCY’s submission showed an awareness of the drama of the site and its potential for a signature supermodern building. The metaphors used in the presentation panels (“like the folded legs of a bather”, “in the tradition of the great Australian beach shack”) set up an expectation of modesty, whereas the composition and materiality seem more risky.

These kinds of site opportunities are rare in Western Australia – only governments and affiliates have access to waterfronts, and there is almost no private ownership of waterfront ground. Perth beaches are therefore sparsely developed, and surf clubs and public amenities are almost the only type. There are some real gems among these, such as the brutal Floreat and City Beach shower blocks by Forbes and Fitzhardinge. Most Perth people love this emptiness and oppose any development – and they like their beach buildings to have an abandoned look. However, there has been a lot of money around Perth lately, and a lot of new people building, and tastes have started to change. For a handful of crusty aficionados (i.e. architects), the golden period of Perth’s modern architecture was around the 1960s, catalysed by the Pilbara resources boom and the Empire Games projects. This left behind a small legacy of skilfully composed though modest residential, public and commercial buildings, many of which have now gone. There was an inventiveness in those buildings, born from a special relationship and shared sense of privation that developed between architects, clients, builders and suppliers, which perhaps accounts for their austerity and discipline. Two booms later, there is little austerity. It has been replaced with lavishness, which has almost become an expectation of all the players. In this way perhaps the profession has followed the market. With a cultural challenge like this, the height restrictions and tricky physical conditions, this site could certainly do with more than one architectural mind addressing the problem.

However, to my mind there is an architectural conceit inherent in the approach to this and many similar competitions – the belief that good architecture comes before good business planning. In my opinion, the winner of this competition was almost inevitable, because of what the client needs right now – an eye-catching model to focus a fundraising campaign, with a “real” brief when the funding is finally found. This, in turn, can be demoralizing for the architect if the final brief and budget do not permit the meaningful realization of the initial concept.

Secondly, the strong appetite for “supermodern” design that is sweeping cashed-up Perth exerts a persuasive, almost irresistible force on the choices of architects and their audiences. The fact that these architects have been honing their product for decades is not as important as the fact that this product is hot right now. This may be good for the client. It means the winning design will find warm support in the wider community. However, it is a pity that the competition brief attempts to cover so much ground at such an early stage of the project development. Architects were asked to consider club identity, budget and site coverage, along with the usual contextual and environmental concerns, at a point when the club cannot yet clearly articulate the problem. The crucial conflict facing the club – how the identity of a surf lifesaving club can combine all of its pressures to invent new streams of income with its traditional cultural associations – is problem enough for this stage of conceptual design. If this vision and business modelling had been more developed, the pragmatic aspects of the building could have been judged against some performance criteria instead of against a feeling of enthusiastic possibility, which is in all of the submissions. It may not have changed the winner, but it might have produced a more satisfactory ongoing process.

Design competitions are also problematic for the architecture profession at large because they are, by nature, anti-professional. They allow new ideas to supplant established ones, new and untested firms to be rewarded over known and established entities. In this way they have the potential to subvert established professional hierarchies, which are built on replicable values that reside partly outside of individual identity, such as professional knowledge and experience, and instead prioritize personality-based artistic and creative values. Design competitions have much in common with art and food prizes, in that they have a lot to do with taste. It is possible to see competitions as a form of professional tender-for-services, and of course some competitions take this form, but these aren’t the competitions that we architects look to for our highest design aspirations. And this competition was really trying to find the right design, the right architecture, as much as the right people.

So, why do architects enter so willingly? The truth is, many don’t. (Studies show that less than ten percent of firms participate in competitions.) However, architectural competitions also form part of a compelling mythology that we collectively prize, even though it may weaken our commercial position in the marketplace. Architects compete not just for the economic benefit, but also for architecturally specific cultural and symbolic capital, which is an essential measure of success within the field. These contests have significance at the scale of the individual and at the scale of the collective. Perhaps what we see are little cultural contests in which capital is won and lost and a firm is capable of building its reputation whether or not the outcome leads to a commission.

So, in the case of this competition, aside from the likelihood or unlikelihood of the commission proceeding, we can read the identification that firms have with their symbolic image projected through their submissions, and also how jury choice and audience reception provide markers in style wars. Unfortunately, architectural services also have a value external to their field, as they constitute society’s economic investment in the profession’s human capital. These external values can only be augmented by the internal values of architecture if these internal values can gain currency outside. In Perth it is still unclear whether the values are set from within or without. In this competition, as in many, despite the sincere and talented work by all concerned, I believe there has been considerable confusion of both sets of values.

The polished presentation of the winning entry by Spaceagency in collaboration with mOrq, which derives its crisp geometric form from the deformed tea-trees on site.

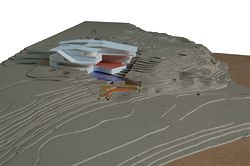

Commended entry by Iredale Pedersen Hook, based on ideas of viewing and surveillance.

Entry by Jones Coulter Young, which explores the dramatic potential of the site for a signature building.

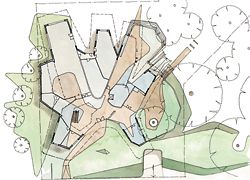

Entry by Donaldson + Warn, which develops the earlier utilitarian clubhouse model.

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 May 2008

Words:

Romest Goonewardene

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2008