BUILDING DIVERSITY

FIRST PLACE Kieran Wong, CODA Studio—team members Emma Williamson, Renae Tapley, Stephen Hicks, Brett Mitchell.

SECOND PLACE Simon Anderson, University of Western Australia -team members Jennie Officer, Trent Woods.

THIRD PLACE Jon Johannsen, Architects Johannsen + Associates -team members Gabrielle Gering, Yvette Olsen, Amelia Capella.

HIGHLY COMMENDED Graham Crist, Antarctica Group—team members Diego Ramirez, Simon Whibley, John Doyle, Daniel Yusko.

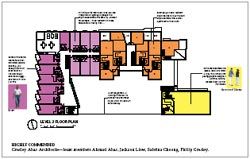

HIGHLY COMMENDED Gresley Abas Architects—team members Ahmad Abas, Jackson Liew, Sabrina Cheong, Philip Gresley.

Philip Goldswain reviews the outcome of a recent ideas competition for new models of socially diverse housing.

The ideas competition offers a rare opportunity to publicly articulate the speculative potential of architecture. As part of the Building for Diversity National Housing Conference, the Department of Housing and Works and the East Perth Redevelopment Authority proposed such a competition, which sought to investigate, within the process of urban renewal, new models of socially diverse housing.

A frayed piece of urban fabric, denuded as a result of the Northbridge Tunnel project, was chosen as the site for conjecture. This site is in an area of urban transition, between a monocultural “entertainment precinct” and disappearing light-industrial and emerging residential fabric. It is bound by Newcastle Street to the north and a proposed twelve-metre-high car park to the south. The demanding brief specified hostel accommodation for single men, and community housing to be determined by the entrant. An existing single-storey heritage building was to be integrated into the retail and commercial mix at ground. A response to demographic and urban shifts, as both architectural and habitational phenomena, was fundamental to the competition.

The winning scheme, by CODA Studio, proposes ambiguous occupation in a hybrid form. Accommodation is housed in two familiar forms – the perimeter and slab block – reconfigured around an elevated, stepped garden. The combination of these types allows the simultaneous interrogation of two modes of urban engagement. The perimeter block conforms to the brief’s latent aspiration for a familiar nineteenthcentury street edge, while the slab block allows a formal investigation of one of Modernism’s failed utopian programmes – the relationship between a building and its artificial ground. The resulting scheme happily conforms to the antipodean tradition of reinterpreting European models, where such models lose their singularity and reappear in a unique pidgin architectural dialect. CODA’s new urban ground, shared by both blocks, can be read as an expanded English terrace garden and/or as the liberated ground plain of the Unite model. This garden connects the disparate forms together in a new state of hybridity. In the shifting landscape of urban renewal and demographic change this lack of fixity is perhaps architecture’s most appropriate response. Further, CODA proposes a diversity that is manifested in “dwelling” rather than articulated through built form. For example, a series of diagrams explains the potential reconfiguration of a single communityhousing apartment type for a photographer, a copywriter, a yoga instructor or a fashion designer. The innate transience in this occupation seems to suggest a domestic correlation to the scheme’s urban multiplicity.

Simon Anderson’s second-placed scheme poses a moment of rational clarity, with a more defined and resolute form that draws stylistic cues from his own small-scale residential projects. The Newcastle Street elevation bears an uncanny resemblance to Anderson’s Killarney Street House (2005) or Broome Street House (2004). In inflating these domestic references, with their asymmetrical elevations and slipped balustrading, to an institutional scale Anderson plays with their formal resolution. The double-height voids are enlarged, maintaining the scale of the domestic project, while the articulated depth of the houses is flattened. In its new form the elevation begins to evoke the apartments of Geoffrey Summerhayes or Hobbs Winning from the late 1960s and early 1970s – crisp, cubic forms whose openings seem carved out of a white, sun-drenched block and whose solid balconies read as slipped planes of the same form. Anderson’s Newcastle Street elevation denies a homogeneous facade in preference for a direct translation of the diversity of units contained in the block. As well as the variations on the hotel-room model seen in many schemes, Anderson offers split-level apartments, three versions of the hostel units, and one- and two-bedroom apartments. Kitchens and wet areas are treated as linear or block elements pushed against a wall or inserted into a single space to divide it into spatial zones. The scheme has a clever stepped section that lets sunlight penetrate deep into the building in winter, while shading the glazed facades in summer.

The third-placed scheme by Johannsen + Associates is the most pragmatic and buildable of the awarded projects. Its form would sit comfortably with the other speculative apartments that have begun to appear in Northbridge. It also has the most convincing integration of the historic shell of Scruth’s Furniture Showroom, albeit predominately as the backdrop to a cafe.

Typologically, it shares with other schemes the strategy of separate perimeter and walk-up apartment blocks.

In their commended scheme, Antarctica Group propose a more radical interpretation of these typologies and prioritize the building’s role as an urban-scale object.

A projecting canopy and a void in the built structure create a public space, a vertical and horizontal chamfer to their version of the perimeter apartment block. This two-storey void is the location for weekend markets or the over-spill of the adjacent cafe. In the building, this “public corner” is manifest as the communal lounges that link the wings of the hostel accommodation. The building proposes a nicely ambiguous relationship with the urban condition – the block’s articulated canopy engages with the setback and form of the remaining built fabric, while the perimeter block veers away from a direct connection with the street.

The four-storey walk-up apartment building is understated in the entry’s presentation.

Its modularity allows a variety of planning arrangements, while the highly rational planning promises future adaptability and flexibility. The proposed limiting of on-site parking means that Antarctica was liberated from dealing with the spatially hungry concerns of the car. However, the resulting courtyard between the buildings is rendered unconvincingly and the walk-up’s sunken private gardens seem unappealing.

A humanist narrative organizes the other commended scheme by Gresley Abas.

Vignettes of occupants’ lives reveal the architects’ consideration of the scheme’s eventual and hopefully multifarious inhabitation. Hostel units can be adapted to have shared or private facilities. Small variations in bathroom, kitchen and balcony arrangements provide individualized hostel rooms, while the transition from supported to independent living has an architectural manifestation.

The thoughtful response of both the profession and the academy to the challenges of the brief gives a small glimpse into the possibilities for the terrain vague of our cities. In addition to these architectural and urban propositions, the careful consideration of the spaces created for people on the margins of society reveals an interest beyond the merely formal.

Hopefully the success of this exercise will prompt the organizer and sponsors to propose future experiments that offer young and emerging practices, such as the ones acknowledged in this competition, the opportunity to implement their ideas in built form. PHILIP GOLDSWAIN IS A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA.