NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

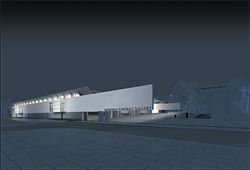

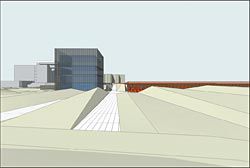

The winning entry by Johnson Pilton Walker, as seen on arrival.

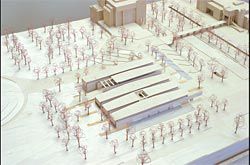

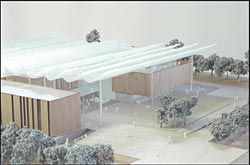

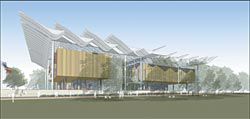

Models of the shortlisted entries. Top to bottom: the winning scheme by Johnson Pilton Walker; Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp; Denton Corker Marshall; Peddle Thorp and Walker Sydney; Nicholas Grimshaw and Partners; rendering of scheme by Sean Godsell Architects and Peddle Thorp Melbourne.

Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp

Denton Corker Marshall

Nicholas Grimshaw and Partners

Sean Godsell Architects and Peddle Thorp Melbourne

Peddle Thorp and Walker Sydney

Johnson Pilton Walker

Laura Harding considers the competition for the new National Portrait Gallery.

At the existing home of the National Portrait Gallery, in the former library of Old Parliament House, Clifton Pugh’s Australians are temporarily reunited. The portrait of Sir John Kerr, painted by Pugh in the year of the Dismissal, smirks knowingly across the room towards the wall occupied by Pugh’s 1972 Archibald Prize-winning portrait of the Hon. Edward Gough Whitlam. Whitlam’s face emerges from the portrait’s abstracted background into sharp focus, fixing the viewer with a steady, provocative gaze – forbidding you to turn your back on him to contemplate his nemesis.

The lively interplay of portraits with the viewer, their architectural setting and each other is the essence of the National Portrait Gallery. Its collection forms an energetic, unscripted and evolving cultural narrative.

To wander the rooms of the gallery is to assemble a highly personalized historic account, refreshingly free of didacticism and constructed meaning. To lock eyes with the portraits in the collection is to discover a surprisingly moving national history, replete with the contradictions, complexity, strength and frailty of those depicted. The primary role of the new National Portrait Gallery is to set the mise en scène for the potent encounter of viewer and subject.

Locating the new National Portrait Gallery in the Parliamentary Triangle, on the edge of the Griffin Land Axis, between the High Court, the National Art Gallery and Reconciliation Place, poses a fascinating but complex architectural proposition – it asks a single work of architecture to reconcile the intimate scale of the engagement of portraiture with the nationalist grandeur of the capital. The six finalists in the recently concluded international design competition have positioned themselves decisively in relation to this central question.

Denton Corker Marshall and Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp (FJMT) separated the intimate expression of the gallery spaces from the iconic presence of the institution, each providing a series of self-contained gallery boxes, clustered beneath an oversailing roof canopy. FJMT’s roof is a crisp, white field of Beyeler-esque aerofoil sections, formed to reflect light into the gallery spaces below. The inflated scale of the large blades unfortunately tends to smother the more finely worked, vertically striated glass and timber-clad galleries beneath. The language of these more intimately scaled elements evokes Auguste Perret’s dictum that vertically oriented openings frame the human proportion – capturing the viewing public in thin windows that transform their silhouettes into animated portraits on the facades of the building.

Denton Corker Marshall proposed an exquisite moire pattern of gridded punctures in their filigree roof – peeled up at the corner to signify the building’s entry on King Edward Terrace and supported by a fringe of densely spaced, needle-like columns. Its speckled light and shimmering surface are visually arresting, but favour an aerial vantage point. From below, only the interstitial and peripheral spaces in the building enjoy the playful articulation and stunning light quality of the canopy.

The gallery spaces are housed in more environmentally controlled timber forms, necessarily protected from the highly patterned light drawn from the signature roof.

The reliance on artificial lighting in many of the proposals is curious. The National Portrait Gallery has a strong curatorial preference for the use of indirect natural light in their gallery spaces – Director Andrew Sayers firmly believes that its vital and changeable quality is essential for, quite literally, bringing to light the vitality and vividness of their collection. Contrary to this, two proposals investigated the excavation of gallery spaces on the site.

Nicholas Grimshaw and Partners posited an in-between scheme – a monumental, ramped forecourt tapering into a subterranean base, unified by a floating roof poised at the level of the natural tree canopy. Despite the lyrical quality of the sectional diagram, the realization of the canopy lacked an appropriate fineness, having instead an imposing institutional weight more readily associated with transport infrastructure. The gallery spaces appear to be a secondary concern when measured against the overstated drama of the inclined landscape and entry court.

Sean Godsell/Peddle Thorp Melbourne set their proposal within a wrinkled landscape carpet. Its extensive excavated structure is sheathed in a rusty, punctured carapace of oxidized steel cells that skims the surface of the site in a manner reminiscent of Dominique Perrault’s Olympic velodrome and swimming hall in Berlin. The shell is a beautifully considered climate-modifying skin, neatly described by its authors as having “an element of bush mechanic” in its tectonic. Despite this, it feels gestural to revel in the tectonic magnificence of a light filtering element that is divorced from the building’s raison d’être, the gallery spaces themselves, which are inset and isolated from the building’s luminous perimeter.

Peddle Thorp and Walker Sydney offered a cellular gallery arrangement, encrusted with a thick layer of supporting rooms and services. The top-lit and well-proportioned galleries offered a range of spaces that seemed well matched to the diversity of the National Portrait Gallery’s collection.

However, the scheme’s enclosure lacked the vitality and architectural quality of the other proposals. The decision to reduce the scale of the building to a symbolic “Australian domicile” complete with single-storey verandah and garden on its north-east edge was an incomprehensible response to the scale of the Land Axis and Lake Burley Griffin foreshore.

Johnson Pilton Walker’s winning proposal occupied solitary territory among the six.

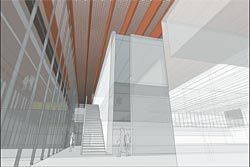

With a nod to its High-Modernist neighbours it evokes the definitive work of Louis Kahn – the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Deftly arranging its parallel bars perpendicular to the Land Axis, JPW’s proposal effortlessly resolves the tension between the competing elements of Reconciliation Place, the King Edward Terrace frontage, the High Court and the National Art Gallery link – creating a range of understated and subtle connections between the building and its surrounding civic elements.

Arranging its gallery spaces on a single level, the building’s primary formal expression is defined by its vaulted roofs, and specifically the transmission of light into the gallery spaces themselves. A series of folded plywood trusses support tapering roofs that gently arc in their longitudinal direction, subtly varying light levels along the length of the galleries. The rigour of its diagram valorizes the gallery spaces, rendering the servicing and support elements of the building almost imperceptible. Small openings on its eastern and western edges provide intermittent glimpses of the landscape beyond, offering moments of respite and recovery for gallery patrons.

The proposal’s civic scale is yet to find its full expression in the powerful linear elevations facing King Edward Terrace and Lake Burley Griffin. The thin blade walls extending from the building to mark the forecourt and entry space jar with the tectonic force and sophistication of the scheme proper, but as a whole the weight of the scheme is a decidedly comfortable fit for the National Portrait Gallery. The question of the institution’s relationship to the nationalist identity of the capital remains.

Many of the entrants’ written submissions are littered with hackneyed references to the creation of “a uniquely Australian architecture” interpreting the “egalitarian”, “open” and “larrikin” character of Australians. Despite its rhetoric, the strength of JPW’s scheme is that it understands that the National Portrait Gallery’s Australians can quite ably and eloquently speak for themselves. It astutely insists that the provision of a quietly dignified and reflective place in which to commune with them is simply enough. LAURA HARDING IS AN ARCHITECT WITH HILL THALIS ARCHITECTURE + URBAN DESIGN.