In 1950s Australia, places of worship were a pivotal component in the construction of culture and community in rural and suburban expansion. However, the subsequent significance of these buildings has been largely unrecognized. Philip Goad and Lisa Marie Daunt introduce some of the country’s most intriguing experiments with a new, modernist language for ecclesiastical architecture.

The postwar religious building has been largely overlooked in histories of Australian architecture. The reasons for this are not clear and the lacuna is not justified, especially as in the 1950s, the design of these buildings – which encompassed ideas of faith – intersected with increasing global attention on themes of monumentality, symbolism and formal expression. This is not to say that there was no discussion of religious buildings at the time in Australia’s professional and popular press; there was. But the subsequent significance of these buildings has not been recognized in terms of their contribution to Australian architecture nor their role in the construction of culture and community, where they served as pivotal foci in Australia’s postwar rural and suburban expansion. This Dossier offers a glimpse into that rich and relatively untapped world, where questions of space, structure, art and representation all collided – often with unexpected results.

Canberra’s first mosque, with dome and minaret, in Yarralumla, ACT. Design by Gerd and Renate Block (c. 1961).

Image: Mark Strizic, published in Cross-Section, no. 110, December 1961, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne

In 1954, Robin Boyd claimed, “Church builders are in a dilemma.” 1 He was appalled by the remodelling of a church in South Yarra in “a sort of Australian Rules Baroque” and asked that designers “rise above utility and answer the challenge to express a spirit beyond the desire for shelter.”2 Four years later, Architecture in Australia devoted its April–June 1958 issue to religious buildings. In it, Sydney architect Milo Dunphy, one of the country’s most articulate spokespeople on modern architecture and religion, wrote that “we can no longer support the catatonic and confused Dodo of traditional church building.”3 His argument was that contemporary architects had a host of new tools with which to reinvent the nature and form of sacred space. Importantly, Dunphy acknowledged the “cheap church hall” as a defining element of Australian religious architecture. The following year, in the exhibition Architecture and Imagery: Four New Buildings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, two of the four buildings were churches.4 While the other two buildings — Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House and Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal in New York — have since become world-famous, the two churches — Guillaume Gillet’s Notre Dame de Royan, France, and Harrison and Abramovitz’s First Presbyterian Church at Stamford, Connecticut — have fared less favourably in the annals of architectural history. It is as if the semiotic crisis of modern architecture suggested by these four buildings in the late 1950s could only be resolved by editing out the challenges (and arguably the postmodern answers) posed by the religious building. Spirit, representation and tradition were simply too hard. In an increasing secular world, it was easier to remove religion from modernism’s trajectory.

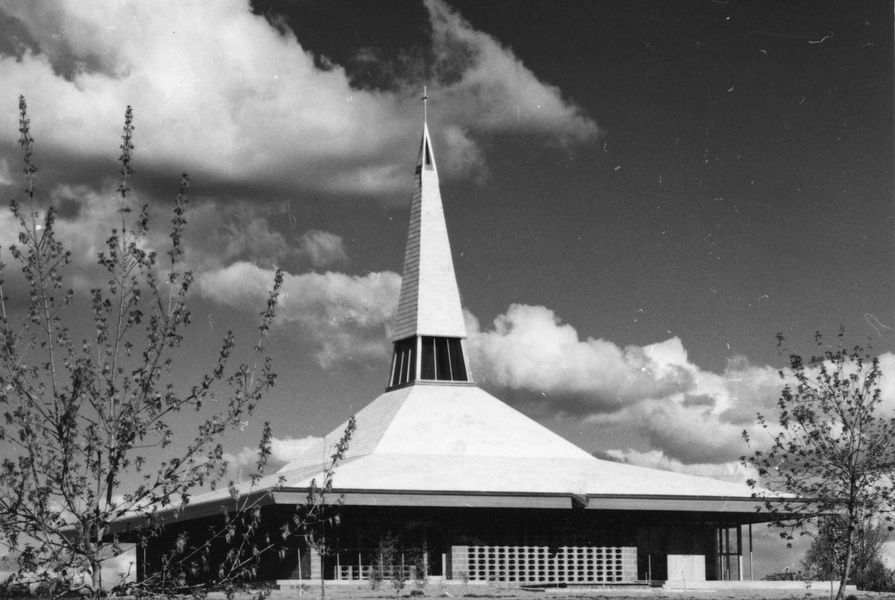

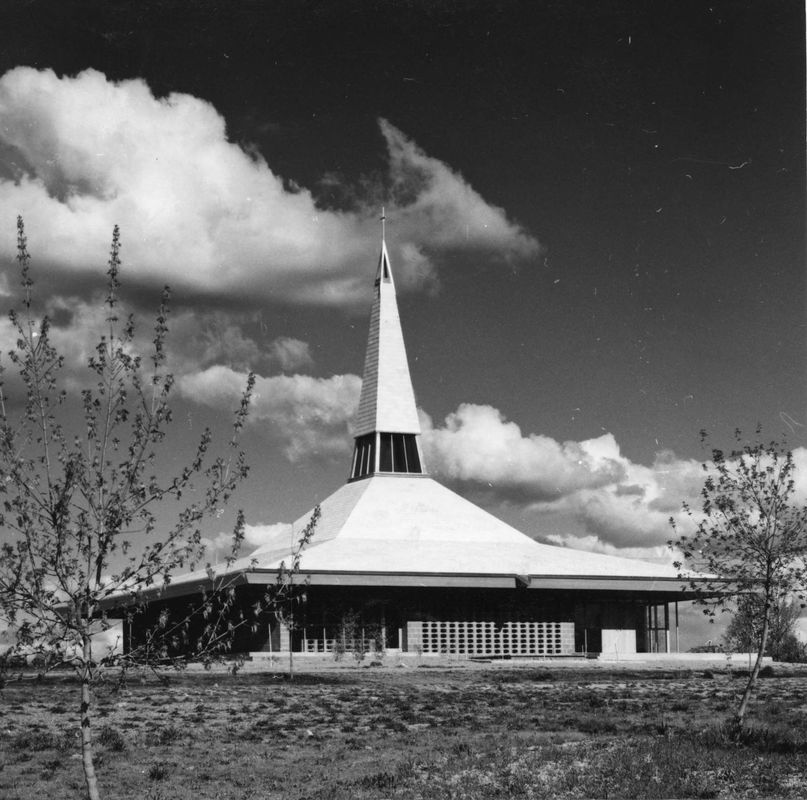

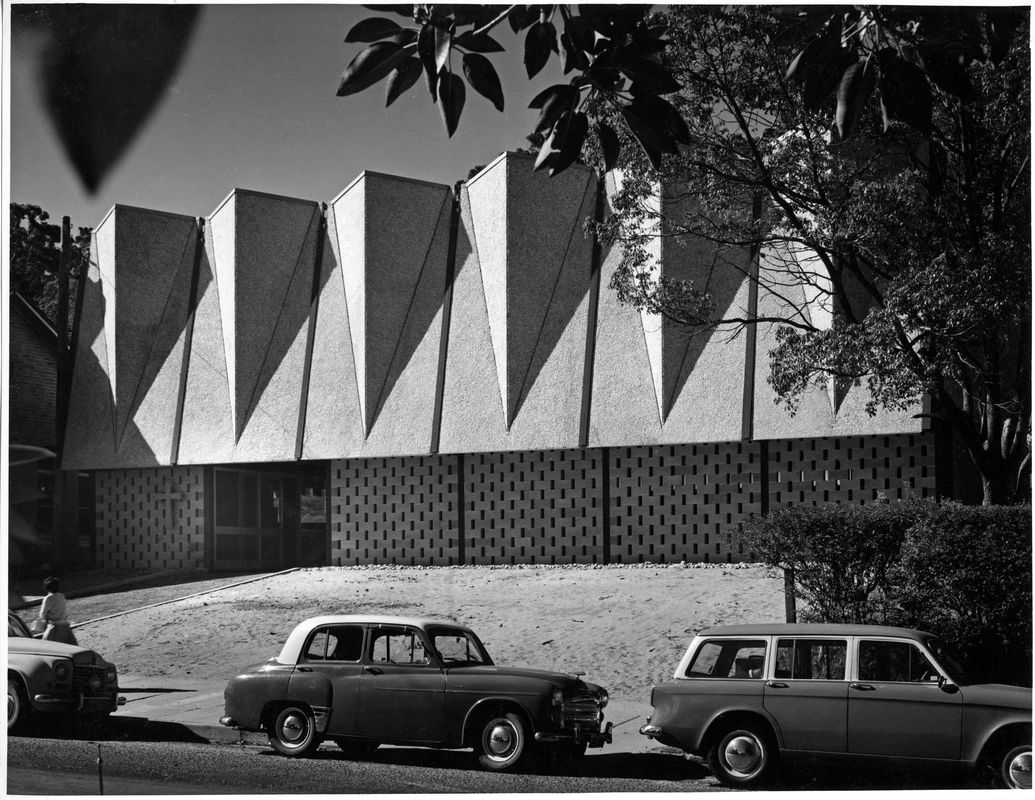

St Andrews Presbyterian Church, Gosford, NSW, designed by Loder and Dunphy (c. 1960, demolished 2002). Milo Dunphy was one of Australia’s most articulate spokespeople on religion and modern architecture.

Image: David Moore, published in Cross-Section , no. 95, September 1960, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne

After World War II, rapid population growth in Australia led to a construction boom, not just in housing and education but also, significantly, in religious buildings. Each denomination, depending on circumstance and aspirations, played a key role in defining urban and suburban development, alongside government agencies, developers and project home builders. This proliferation of new religious buildings prompted re-evaluations of religion’s symbolic role in society. It also heralded a phase of experimentation in the design of individual religious buildings and in their urban placement, which, in many locations, affirmed their potency in forging new postwar communities.

The five buildings presented in this Dossier were chosen from the fourteen papers presented at Constructing Religious Territories: Community, Identity and Agency in Australia’s Modern Religious Architecture, a symposium convened by Lisa Marie Daunt and Philip Goad on 24 August 2018 at the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne. This symposium, the first of its kind in Australia, investigated connections between religious architecture, urban design and community formation. The five case studies offer just a tiny sample of the thousands of religious buildings built across Australia between 1945 and 1975.

South Head and District Synagogue in Dover Heights, NSW by Neville Gruzman (c. 1958, demolished). A suspended canopy dome marked the entry off the street into the modern synagogue.

Image: Max Dupain, published in Cross-Section, no. 72, October 1958, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne

Isabel Rousset and Annette Condello’s piece on the New Norcia Catholic Pilgrim Cathedral and Abbey, an avant-garde design for New Norcia in Western Australia by renowned Italian engineer-architect Pier Luigi Nervi, sets the scene. Though unrealized, the widely-published scheme highlighted the experimental potential of modern ecclesiastical architecture for architects and clergy alike. In her account of the Holy Family Catholic Church at Indooroopilly, Queensland, Lisa Marie Daunt examines a progressive design by Douglas and Barnes that was influenced by Nervi’s design, built when the Catholic Church was rethinking ecclesiastical architecture to cater for modern society. However, as the 1960s progressed, the Catholic Church and the other Christian denominations moved away from monumental, landmark buildings in favour of international ideas for liturgical renewal and worship spaces in which congregation and priest participated in the liturgy together. Designs that were sensitive to communities’ needs and responsive to urban context grew in popularity. Stuart King’s discussion of the Church of the Incarnation at Lindisfarne in Tasmania by architect Lindsay Wallace Johnston exemplifies this new direction.

The postwar boom in religious building was evident across every faith. Catherine Townsend’s piece on Kurt Popper’s Elwood Talmud Torah Synagogue in the Melbourne suburb of Elwood details a remarkable story of reinvention by a community fleeing persecution during World War II (page 72). The émigré Jewish communities of Melbourne brought with them from Europe new ideas for modern architecture, which they embedded, without hesitation, into new synagogue designs – a contrast to the arguably delayed take-up of modern architecture by Christian communities.

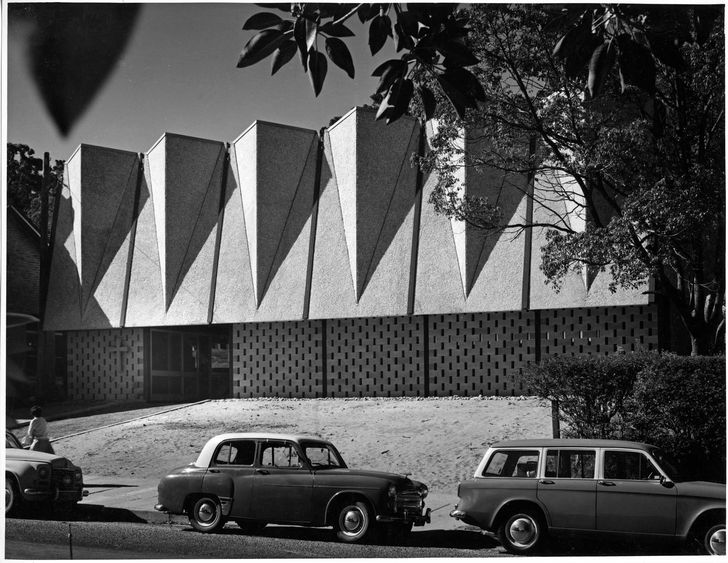

Michael Dysart’s expressive form for a chapel for the migrant Polish Catholic community in Blacktown, NSW. Marayong Memorial Chapel for Polish War Dead (Polish War Memorial Chapel, c. 1967).

Image: Max Dupain, published in Cross-Section, no. 207, February 1970, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne

The construction of new religious buildings was not confined to the cities. Many rural and regional communities replaced their existing churches with new ones, displaying ambitious aspirations for the future. Elizabeth Richardson’s piece on Muir and Shepherd’s design for the Katamatite Methodist Church in country Victoria details how one regional community sought to achieve its own modern church building, with both congregation and architect intent on designing with modern materials and contemporary structural systems with modest economic means.

Today, many postwar religious buildings are at risk of neglect and demolition. In the decades since their construction, the place of religion in society has shifted dramatically and parishioner numbers have dwindled, leaving many structures redundant. Increased land values have become an understandable temptation for cash-poor religious organizations, often superseding community appreciation for the buildings’ inherent social value and architectural worth. In this social context, advocacy for the protection and care of religious buildings is challenging but necessary. This Dossier opens a window onto five vital postwar experiments with a new language for ecclesiastical architecture, and acts — we hope — as a compelling and relevant companion piece to the contemporary buildings reviewed in this issue of Architecture Australia .

— Philip Goad is Chair of Architecture and Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at the University of Melbourne.

— Lisa Marie Daunt is an architect completing her PhD at the University of Queensland on the relationship between modern church design and community in postwar Queensland.

Authors’ note

We would like to thank Barry Bergdoll and Elizabeth Richardson for drawing our attention to various sources in the preparation of this article.

Footnotes

1. Robin Boyd, “Church builders are in a dilemma,” The Herald (Melbourne), 23 November 1954,16.

2. The church in question was the Roman Catholic Church of St Thomas Aquinas in Bromby Street, South Yarra (architect: T. G. Payne).

3. Milo Dunphy, “4 Aspects of Church Design,” Architecture in Australia, vol 47 no 2, April–June 1958, 59.

4. Arthur Drexler and Wilder Green, Four new buildings: architecture and imagery (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1959).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 4 Nov 2019

Words:

Philip Goad,

Lisa Marie Daunt

Images:

Cross-Section , no. 110, December 1961, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne,

D. Darian Smith, published in Cross-Section, no. 83, September 1959, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne,

David Moore, published in Cross-Section , no. 95, September 1960, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne,

Mark Strizic, published in Cross-Section, no. 110, December 1961, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne,

Max Dupain, published in Cross-Section, no. 207, February 1970, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne,

Max Dupain, published in Cross-Section, no. 72, October 1958, Architecture Library, University of Melbourne,

Wolfgang Sievers, source: State Library of Victoria

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2019