One of the earliest known artworks in a hospital is William Hogarth’s 1736 mural Christ at the Pool of Bethesda, housed in St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. Not intended for public eyes, this work was instead instructive – diagnostic even – with the figures standing about the healing waters of Bethesda depicting symptoms of diseases that were common at the time.

However bold and radical this was in the eighteenth century, the positioning and deployment of art within hospitals has come a long way. Melbourne-based sound artist Philip Samartzis has worked with Dr Tracey Weiland in initiating a groundbreaking study into the effects that sound and recorded compositions have on the anxiety levels of patients in emergency departments. Through presenting a sample of patients admitted to St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne with one of five sound recordings, they discovered that those patients who listened to either an electro-acoustic musical composition, audio field recordings of natural sounds, or audio field recordings embedded with binaural beats, measured a self-rated level of anxiety that was 10 to 15 percent lower than those in the first two groups.

The Creature sculpture designed by Alexander Knox for the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne.

Image: Shannon McGrath

These findings are remarkable when teamed with evidence-based design research such as that conducted by Roger Ulrich in 1984. Ulrich discovered through a controlled study that the recovery rates of patients who had a view of trees from their window was reduced by almost an entire day. This focus on the healing powers of nature within a hospital is one of the core guiding principles employed in two new Australian children’s hospitals: the Queensland Children’s Hospital (QCH), designed by Lyons Architecture and Conrad Gargett (still under construction), and the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) in Melbourne, designed by Billard Leece Partnership and Bates Smart with HKS as an international adviser. Both buildings draw heavily on structural and creative metaphors of nature in their design and philosophical intentions.

The Lyons/Conrad Gargett QCH is structured as a tree and branch system, whereby the clusters of rooms and gathering points are akin to roots, offering large open vantage points or “family centres” that jut out of the building’s core and provide vast sight lines to the environment. Bates Smart’s RCH, on the other hand, is situated within Melbourne’s Royal Park, which allowed architects to maximize the porosity between the built and the natural environment. Every room at the RCH has a window that opens onto parkland and this ecological thematic is continued in the wayfinding that emulates the strata of the Australian natural environment, from underwater to the treetops and all the creatures therein. Likewise, the colour palette selected for the QCH is drawn from Queensland’s deserts and rainforests.

But how, within these overarching ideas, can art maintain an independent presence or sustain its individual integrity as an artwork? There are certainly opportunities for art to be employed as a therapeutic tool, as with Philip Samartzis’s work, but in both the QCH and the RCH large sculptural commissions have been, or are planned to be, constructed within the building and it is these that are pulled into dialogue with the architecture, for better or worse.

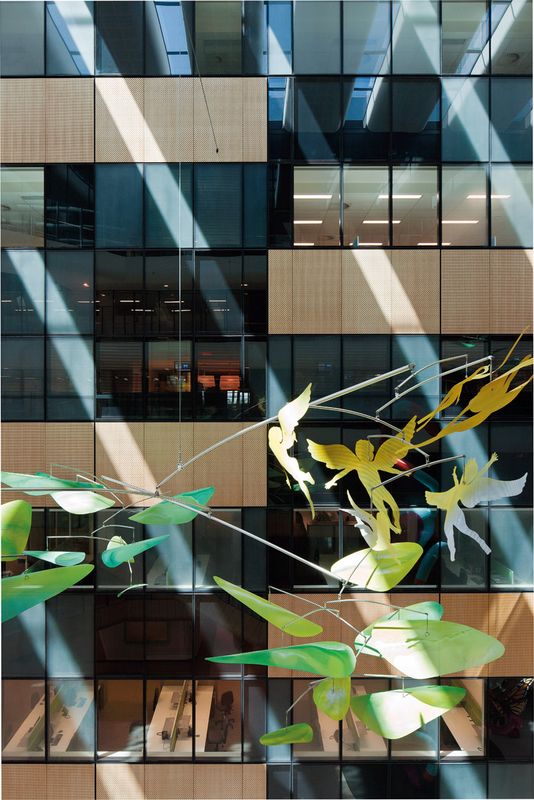

Jade Oakley’s Sky Garden installation at the Royal Children’s Hospital.

Image: Shannon McGrath

For Kristen Whittle of Bates Smart, design director of the new Royal Children’s Hospital, art was present within the hospital design from the earliest point of design conception. Whittle was stimulated by Olafur Eliasson’s sculptural installation at the Tate Modern, London, entitled The Weather Project (2003), which explored notions of experience, mediation and representation. Whittle was struck by this work’s capacity to operate as an emotive opener that short-circuited the banal of the everyday, which as Whittle states “speak of how a person’s mind and body is encoded to enjoy certain natural phenomena and how spatial aesthetics are linked to core emotions.”

For Corbett Lyon, director of Lyons, the incorporation of art in the hospital is also integral to their client’s and team’s ethos. The hospital invited groups of curators to pitch for the role of art consultant and brought on the winning team early in the schematic design stage, which has allowed the architecture and curation to inform each other, working in partnership to communicate the thematic of the building.

Both Whittle and Lyon agree that the function of art is to distract and engage, and for Whittle it is a distraction from the everyday that elevates or separates the visitor experience from their immediate reality – as Eliasson’s work might.

In Melbourne’s RCH this philosophy is articulated in large sculptural commissions by Alexander Knox and Jade Oakley, both of whom have drawn from nature in their works. However, the emphasis in both of these large-scale installations is on the fantastical, whimsical and other-worldy, with each artwork distracting and elevating the viewer in distinct and successful ways.

At the QCH, one idea is to introduce artworks throughout the building as small ruptures in the seamless flow – for example, an artwork beneath the floor that is visible through Perspex, or one that clads the elevator shafts. Lyon also points out the extent to which the client and the architectural design team are approaching an expanded concept of art within the hospital, which encompasses drawing workshops, musical and acrobatic performances, and other more interactive public programs.

A render of the Queensland Children’s Hospital reception area.

Image: Courtesy of Lyons Architecture.

However, while it seems that both approaches draw on evidence-based design theories that focus on the healing power of nature, and also incorporate artwork as a means to divert attention and inspire imaginative responses, their approaches are distinct.

Lyon talks of the artwork at the QCH as independent of the architecture, maintaining that the design is sufficiently robust so as to accommodate strong individual artworks in their own right. Lyon also points out that at times the building invites points of tension where the art and the architecture are free to coexist. Whereas, for Whittle of Bates Smart, art is a means to communicate with the imagination, and is seen as an approach rather than an outcome that is holistic with the entire context of the hospital. Whittle believes that the artworks embedded within the new Royal Children’s Hospital will “combine with adjacent spatial partners to invoke a true splitting open of core clinical and public functions to bring about greater public participation and an overall empowerment of activities within.”

Credits

- Project

- Queensland Children’s Hospital

- Design practice

- Lyons Architecture

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Design practice

- Conrad Gargett

Australia

- Site Details

-

Location

South Brisbane,

Brisbane,

Qld,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Health, Interiors

Type Hospitals

- Client

-

Client name

Queensland Health

Website health.qld.gov.au

Credits

- Project

- Royal Children’s Hospital

- Design practice

- Bates Smart

Australia

- Project Team

- Jeff Copolov, Mark Healey, Kristen Whittle, Andrew Francis, Nicola Lodge, Jane Reiseger, Rosemary Burne, Wai Fong Chin, Lucy Croft, Paola Echeverry, Lynsey Fox, Ross Goldsworthy, Sue Guzick, Tonya Hinde, Claire Hughes, Alice Milledge, Simone Morgan, Mairead Murphy, Daniel Rafter, Evan Reeves, Anna Spirou, Kathrin Stumpf, Inta Thomas, Elisabetta Zanella, Sarah White

- Design practice

- Billard Leece Partnership

Australia

- Landscape design

- Land Design Partnership

Carlton, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Horticulture

May Horticulture

Irrigation Ten Buuren Irrigation Design

- Site Details

-

Location

50 Flemington Road,

Parkville,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Suburban

Building area 165000 m2

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2011

Design, documentation 43 months

Construction 12 months

Website http://www.batessmart.com.au/#/projects/health/the-new-royal-children's-hospital-parkville-interiors/proj/description0

Category Health, Interiors

Type Hospitals

- Client

-

Client name

Royal Children's Hospital and Lend Lease

Website rch.org.au

Source

Discussion

Published online: 26 Jun 2012

Words:

Emily Cormack

Images:

Courtesy of Lyons Architecture.,

Shannon McGrath

Issue

Artichoke, March 2012