Controls: Do They Work?

| As public places increasingly are built by private enterprises, governments arestruggling to balancecorporate profits and public benefitsvia design controls drenched incontroversy. Philip Grausdiscusses the dilemmas. |

| Around the world, governments are set on a course of deregulation and competition. Privatisation is on the agenda of political groups of most persuasions. In the prevailing view, private initiative is in the public interest. Australia’s federal government appears to have a clear mandate to pursue this path-and it is clear that private enterprise increasingly will design, build and operate the public realm.

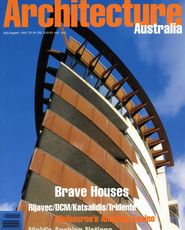

During the 1980s, desire to deregulate the economy was reflected by a call for performance-based design controls. More recently, an alternate view has been put forward by those who believe that control of the public realm has not been sufficiently safeguarded. The words ‘public realm’ appear time and again in the more recent codes. Why is this necessary? Surely market forces will best reflect what the public actually wants, and private enterprise will deliver it. Nowhere is this contradiction more clearly illustrated than in the current furore over Sydney’s East Circular Quay project, erupting next to the Opera House. Strict design controls were applied to shape the development as an appropriate urban form. The Prime Minister of the day negotiated a deal with the city council to allow a hotel and apartments to occupy a length of public road in return for a lower building more in keeping with the form of Circular Quay. On the face of it, this would seem the ideal melding of public good and private initiative. But now that the buildings are going up, there is a public outcry-including demonstrations and calls for their demolition. In recent years, as governments have increasingly sought to deregulate and hand over more responsibility to the private sector, design controls (especially urban) have increasingly referred to ‘the public realm’. In reality, governments are trying to devolve responsibility for providing public places to private interests, while still retaining control over outcomes. It is here that a key contradiction lies. For how can the outcome be assumed without strictly regulating the situation? Two quite different approaches have emerged over the past 10 years or so. Prescription or Performance? The second approach involves far more specific codes- prescriptive controls-intended to provide more certainty. These range from ‘minimalist’ codes, in which only a few basic elements are prescribed, to those containing highly detailed requirements. In general, prescriptive codes have been championed by people seeking a return to traditional architectural styling-and because such forms are well-known, they can be easily prescribed. Exemplifying the prescriptive approach, Prince Charles declared in A Vision of Britain (1987): “We have a second chance. Pray God we can get it right this time.” With Leon Krier and Andres Duany, he established a masterplan and detailed planning code for Poundbury in his Duchy of Cornwall. Not surprisingly, the result looks like a Krier town with Duany Plater-Zyberk new urbanist controls. In many ways, the two approaches-performance and prescriptive-are diametrically opposed; reflecting a schism in planning theory. On one hand, Duany maintains that the modernist, laissez-faire approach to the city is wrong. Change the codes, he maintains, and you change the city. On the other hand, those promoting performance-based controls believe that, given clear performance objectives, the market will efficiently and economically find solutions to meet these objectives. Both approaches have in common a desire for design controls to create a nexus between the market and economic forces on the one hand, and the community and the public domain on the other. But is this notion based on a false dichotomy-one that seems to separate the form of a city from the forces that really shape it? Historical Precedents London, on the other hand, had little need for city walls, and developed, unplanned, as an ‘open city’ free from attack. Even after the Great Fire of 1666, when the opportunity arose to rebuild in a more planned way, the government lacked enough authority to control privately owned land destroyed by the fire. While main streets were widened to minimise the risk of a future fire, the alignments generally were not changed as land on both sides of major streets was generally privately owned. In contrast to London, Paris has been historically controlled by a strong city administration; a factor which facilitated Hausmann’s wilfully planned system of boulevards. In the United States, Chicago architect Daniel Burnham (planner of the 1893 Colombian Exposition) also proposed a clear architectural system in his city plan of 1909. However, the economics of private development-specifically pressures arising from the new type of the tall office building-defeated his ideas. While uniform heights for elevator and non-elevator buildings were established, these controls did not take into account vastly different property prices in various precincts of Chicago, so the controls were progressively forgotten. The plan was only successful in its concept of a waterfront and park system-clearly a scheme which supported rather than hindered property profits. These examples make it evident that successful plans or systems of control must acknowledge the economic and political realities of the times when they are conceived. Architects on Australia’s Controls Sunshine Coast architect Lindsay Clare also believes that simple prescriptive controls are the most desirable. “Sienna had three controls-height, bulk and colour-and voluminous controls don’t achieve much more,” he says. However, he agrees that controls are necessary in areas of rapid growth, including greenfield subdivisions as well as consolidations of existing settlements. Without such controls, Maroochydore has grown into a city which lacks a core precinct-seemingly contradicting its state government designation as a regional centre. Clare also suggests that development control plans need to acknowledge the vernacular architectural character of the region, as gradually evolved from practical responses to local conditions. He laments that some recent DCPs for the Sunshine Coast actually discourage appropriate designs because they impose controls ignorantly imported from colder areas of Australia. As another point, “most codes do not understand scale,” says Clare. In Victoria, Anne Cunningham supports performance controls, as demonstrated by Victoria’s new Good Design Guide, a document which updates AMCORD’s provisions. Performance controls, she says, “allow designers to design projects using basic architectural and urban design principles without being restricted by prescriptive codes. Successful outcomes need good designers as a code will never design a project.” She admits that a major problem with performance codes is that bureaucrats assessing proposals often lack training and confidence to interpret the controls in design terms. Yet many authorities envisage performance controls as design guides capable of generating good outcomes even without the involvement of a qualified designer. Yet, like Clare, she supports the establishment of strong frameworks for urban design. Cunningham suggests that local authorities should prepare strategic plans to underpin performance controls. “Performance controls should be supported but councils require considerable assistance; otherwise the codes will produce boring results that mimic existing situations with little skill or imagination.” Peter Fletcher, originally from Sydney and now practising in Darwin, believes his city requires more regulation to promote a higher degree of architectural quality. He recalls the introduction, by the Department of National Parks in the 1970s, of codes for Koscuiszko that were considered dictatorial by architects of that time. Yet “architects had the opportunity to justify variations to the controls and the results have on the whole been successful.” In Darwin, Cyclone Tracy forced the writing of simple, deemed to comply, controls included in the Building Code of Australia. Yet the greatest influence on the territory’s architectural character, he believes, will always be its tempestuous climate. Designs unresponsive to the local climate are not livable,” Fletcher says. However, Darwin citizens are still regularly delivered buildings designed by interstate firms of architects who do not understand the territory’s seasonal extremes. Also in Darwin, Adrian Welke of Troppo supports performance rather than prescriptive controls, noting that “we would never have been able to do the sort of buildings we did a number of years ago under strict prescriptive design codes. Since that time we have developed our own principles to deal with the tropical climate of the Northern Territory. Funnily enough, these are included in AMCORD’s Practice Notes.” Yet he believes, like Clare, that national codes need to be adapted to suit local circumstances. Sydney architect Peter Reed says that codes must arise from a process of local research and analysis, including community debate. He believes that planning codes also need to promote specific principles-but notes that that such principles can be forgotten. For example, the Northern Territory government promotes Darwin as a ‘green city’-but this aspiration is not reflected in its codes. In Sydney, Philip Cox is suspicious of any controls-believing that ‘planned’ cities are no better than those that have evolved in response to changing circumstances. In fact, he says, many planned environments are dull and lack the excitement and intrigue so important to create a real sense of place. “Design is important-a set of rules is no substitute.” Meanwhile, Cox’s partner, John Richardson, believes that there are two key areas of control: the public domain and the buildings that frame it. “It may be best to have prescriptive controls for the public domain (streets, landscape, etc) and performance codes for buildings.” Stephen Buzacott, a Sydney architect and urban designer, is sceptical of performance controls, saying that local authorities cannot control an outcome without fairly straightforward prescriptive controls. “Planners, who are most commonly the authors of planning and urban design controls, are generally not trained in design-resulting in codes that do not provide certainty with regard to built form.” He believes that prescriptive controls are in the interests of the community, and cites Sydney City Council’s codes as a good recent example of design controls. Sydney’s central zone is controlled by an extensive local environmental plan and a development control plan. Traditional controls for zoning, height, setbacks and FSR are supplemented by detailed ‘urban design’ performance and prescriptive controls including sun planes to maintain solar access to public open space. Running through the code is a traditional view of the city as streets defined by built edges; the street as a room. Modernist towers set on plazas-such as Seidler’s MLC Centre on Martin Place-are strongly discouraged in the council’s plans-yet it has approved Renzo Piano’s plaza-based scheme for the State Office block on Macquarie Street. (The design for East Circular Quay, mentioned earlier, is in accord with the streetlife intent of these controls.) Peter Hooper of Greenway Architects in Adelaide is also sceptical of performance-based controls because he believes the results are often mediocre: “controls are never a substitute for design.” He says that many planning documents, including the City of Adelaide Plan, contain worthy intentions and objectives, but their principles do not always translate into built results. Many of the best buildings break the rules-but Hooper claims there is definitely a need for what he calls ‘good neighbour’ controls for privacy, light, and general amenity. Glenn Murcutt, no stranger to council codes, believes that authorities need to impose controls but these should represent ‘real’ constraints, such as site cover and floor space ratios, not arbitrary stylistic judgements which planners are not trained to make. He proposes four areas needing to be addressed by controls: Typology, Morphology, Materiality and Scale. “The architect, as well as those assessing any proposal, should understand the existing typology and morphology [built form characteristics] of the area.” Murcutt believes that judgment of such issues cannot be made by those without training in design. “Most planners have no training in visual matters and consequently rely on numerical standards to assess a proposal. Prescriptive standards assume that the designer will get it wrong,” he maintains. Drafted by non-designers, detailed controls for built form will usually prescribe past solutions.” In the end, for the non-designers, the only certainty is the past.” No Substitute for Good Design Yet it is becoming clear that prescriptive controls are restrictive and that performance controls alone will not guarantee high quality results. Authorities now need to consider a basket of measures to produce public places of quality-and controls should be only one component. It is unfortunate that many authorities appear to believe that design controls can replace good design by acting as some type of design guide. As has always been the case, creative ideas, insight, careful analysis of existing conditions, and good design are essential. If design is to have any real impact on the public domain, the architectural and design community need to reinforce this point with government authorities, rather than accepting their current focus only on the forms of controls to be. Philip Graus is an architect and urban designer at Cox Richardson in Sydney. He helped design the Olympic Village masterplan. | top The “too high, too long, too wide” scheme now being constructed at East Circular Quay; seen across Sydney Cove from the Overseas Passenger Terminal. At right, behind the Cahill Expressway, are the Royal Automobile Club (brick) and Quay West apartment tower.

above, from top to bottom Photo montages of approved schemes for Sydney’s East Circular Quay, supplied by the Lord Mayor’s Office. editor’s summary All these developments (like the existing railway station and ferry wharves) obscure the Opera House from the north-west edge of the city-and ignore former Premier Neville Wran’s televised acknowledgement, after a 1988 RAIA ideas competition, that Sydney clearly wanted low buildings leading to the Opera House. Although conforming at all times to regulated (and diminishing) envelopes, these schemes also block views and access between the water and the Botanic Gardens surrounding historic Government House. The 1994 scheme by Peddle Thorp was also intensively massaged on its aesthetics and amenities by the Sydney City Council. |