In Australia, the average life expectancy of Indigenous people is estimated to be eight years lower than that of non-Indigenous people.1 As a result of years of health disparity, Indigenous people access aged care at a much younger age than non-Indigenous people. This is acknowledged by federal government policy that enables Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders aged 50 years and over to access aged care services, 10 years earlier than their non- Indigenous counterparts. A submission to the 2018 Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety by the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation highlighted the under-representation of Indigenous people in residential aged care services and the lack of culturally appropriate facilities.2

Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population has increased significantly over the past 25 years, especially in areas such as South East Queensland, where this population is both ageing and highly urbanized. The significant under-representation of ageing Indigenous people in the Australian aged care system is the result of a lack of cultural understanding, culturally appropriate environments and cultural safety for these people. Little research has been done on culturally appropriate design for ageing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the Australian aged care quality standards, guides and recommendations are typically generic, giving little sense of what can be done to improve the experience of these populations through the physical environment and architectural interventions. By comparison, evidence-based research and culturally appropriate design is widely used in Indigenous housing, courthouses, prisons and, recently, healthcare facilities. Given the accepted practice in these building typologies, how can aged care design also be improved to enhance the physical environment in residential aged care facilities to better support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?

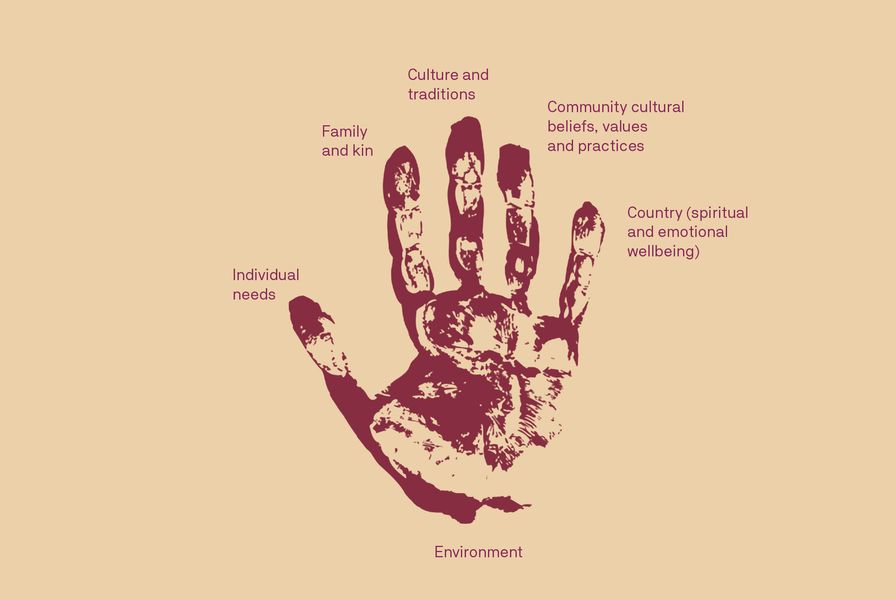

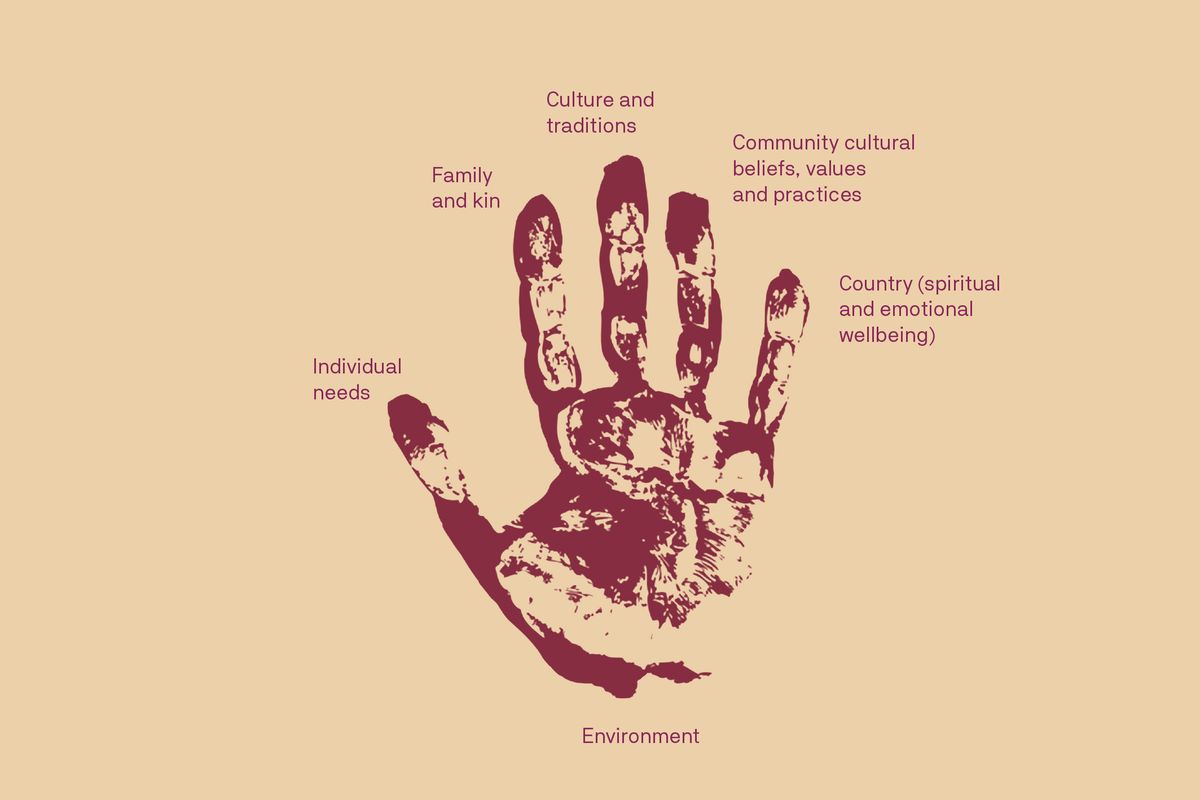

My doctoral research at the University of Queensland uses a cross-disciplinary case study approach to answer questions surrounding Indigenous residents’ experiences in aged care facilities, considering the design implications of an Indigenous construct of wellbeing centred around individual health needs; connections to Country, family, kin and community; and cultural and social preferences. The research seeks to provide design practices and aged care providers with information to help improve and enhance the experiences of older Indigenous people living in aged care facilities by addressing the needs of residents with diverse cultural backgrounds. The case study research was carried out across four residential aged care facilities in South East Queensland: Jimbelunga Nursing Centre in Eagleby, Brisbane and Nareeba Moopi Moopi Pa on North Stradbroke Island (both designed by Conrad Gargett); Georgina Margaret Davidson Thompson Hostel in metropolitan Brisbane; and the Ny-Ku Byun Elders Village in Cherbourg, 280 kilometres north-west of Brisbane.

The research, which is still being undertaken, has begun to describe varied and overlapping social and cultural spatial implications for designers and service- providers involved in the planning and design of residential aged care facilities. For example, nursing staff across the facilities commonly observed that Indigenous residents’ family and kinship connections result in more visitors during event celebrations such as NAIDOC Week, Christmas and National Sorry Day. Research participants suggested that the size of existing spaces in the facilities is often inadequate to accommodate the influx of visitors during these events, with temporary marquees having to be set up to accommodate guests. If residential aged care is to have any relevance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, its design needs to consider how spaces can be made more flexible to better address their needs and to enable them to maintain their traditions, culture and connection to communities. Interestingly, in a design project described in Architecture Australia’s May/June 2018 issue on housing diversity, Nigel Bertram and Catherine Murphy include flexible spaces as one of the recommended design principles for ageing in place.3

A similar spatial demand also occurs during a resident’s end-of-life phase, when there can be a continuous flow of visitors. Participants said that a lack of space and privacy inhibits residents’ family members from speaking with clinicians and others about end-of-life care. Social and cultural preferences mean that many of these discussions need to occur without the resident present – but the appropriate space is not available. Participants suggested the provision of a family-care room where family members could make a cup of tea or grieve and moan/wail together. It was recognized across all four sites that this room should have outdoor access and connections to the natural environment. A lack of space and demand for a family room to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people during end-of-life care have also been described in hospital settings.

Residents, visitors and staff indicated a strong preference for outdoor spaces, and ease of access to outdoor spaces, at aged care facilities. The outdoor environment offers residents a restorative and supportive space, and opportunities to socialize and have a yarn with other residents and community groups. Participants also mentioned the benefit of cultural symbolism at aged care facilities, such as Indigenous paintings and artefacts, and portraits of famous Indigenous sportspeople, which are welcoming and identifiable to residents and visitors.

These are just a few of my research findings into the design implications of an Indigenous construct of wellbeing in a residential aged care setting in an urban context. It is important to note that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are diverse and have different backgrounds, traditions and life experiences. This means that they might not share identical practices, values, beliefs or lifestyles and, as a result, their needs vary. Indigenous social and cultural preferences challenge current design guidelines in residential aged care settings and the common perception that one size fits all. For residential aged care to be culturally safe, welcoming and relevant to older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, purposeful consultation is required, along with an interdisciplinary team coming together to provide an appropriate and comprehensive design solution. While this research focuses on the design implications in residential aged care settings for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the care needs of these people should also be considered at a community level. If architecture and design is culturally and socially inclusive in a community-care setting, older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are likely to be able to remain within the community, and outside aged care settings, for longer.

1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, “Life Expectancy and Deaths,” 2019, aihw.gov.au/reports-data/ health-conditions-disability-deaths/life-expectancy-deaths/overview (accessed 25 June 2021).

2. NACCHO (National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation), “Submission in response to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety: Consultation paper on program design,” January 2020, agedcare. royalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-09/ AWF.660.00185.0001.pdf (accessed 25 June 2021).

3. Nigel Bertam and Catherine Murphy, “The Space of Ageing,” Architecture Australia , vol 107 no 3, May/Jun 2018, 46–50.

Community cultural beliefs, values and practices

Country (spiritual and emotional wellbeing)

Source

Discussion

Published online: 2 Dec 2021

Words:

Yim Eng Ng

Images:

Supplied

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2021