Embraced by the folds of the Yarra Valley’s mountainous upper reaches, approximately seventy kilometres east of Melbourne, is one of Victoria’s great public works of the interwar period. Many Victorians know it through Sunday drives, childhood picnics on its shaded lawns, vertigo-inducing strolls atop its massive dam wall and the excitement of its seasonal torrents cascading down the spillway. Often referred to simply as Maroondah Dam, its creation was an exercise in monument building. It was also an experiment.

Maroondah Reservoir, constructed between 1920 and 1927 by the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW), was the first reservoir built in Victoria under the MMBW’s controversial closed catchment policy. This policy was designed to protect the purity of Melbourne’s drinking water by denying all public access to water catchments, but compensated this loss by providing new public parkland. Thus the development of attractive and publicly accessible parkland as an adjunct to the new reservoir was central to the success of the venture. The MMBW had previously carried out retrospective planting in older reservoir reserves, such as Yan Yean and Toorourrong, to improve their attractiveness to visitors and prevent erosion. But including landscaped public parkland as an integral part of the design for a new reservoir had not been previously attempted in Victoria. Maroondah Reservoir would be a first.

The area’s rugged, forested majesty demanded a designed landscape that was equally grand, and the MMBW spared no effort in its creation. Functional dam infrastructure was designed to embellish the grandeur of the natural scenery in which it sat. The massive cyclopean rubble and concrete dam wall thrown across the Watts River valley was topped with a walkway finished with ornamental balustrading and pyramidal capping. A highly decorative, classically- inspired outlet tower and twin valve houses complemented the massive structure.

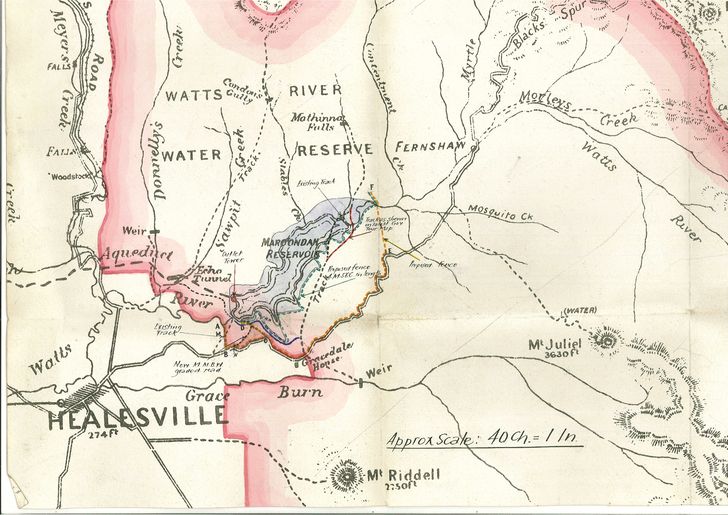

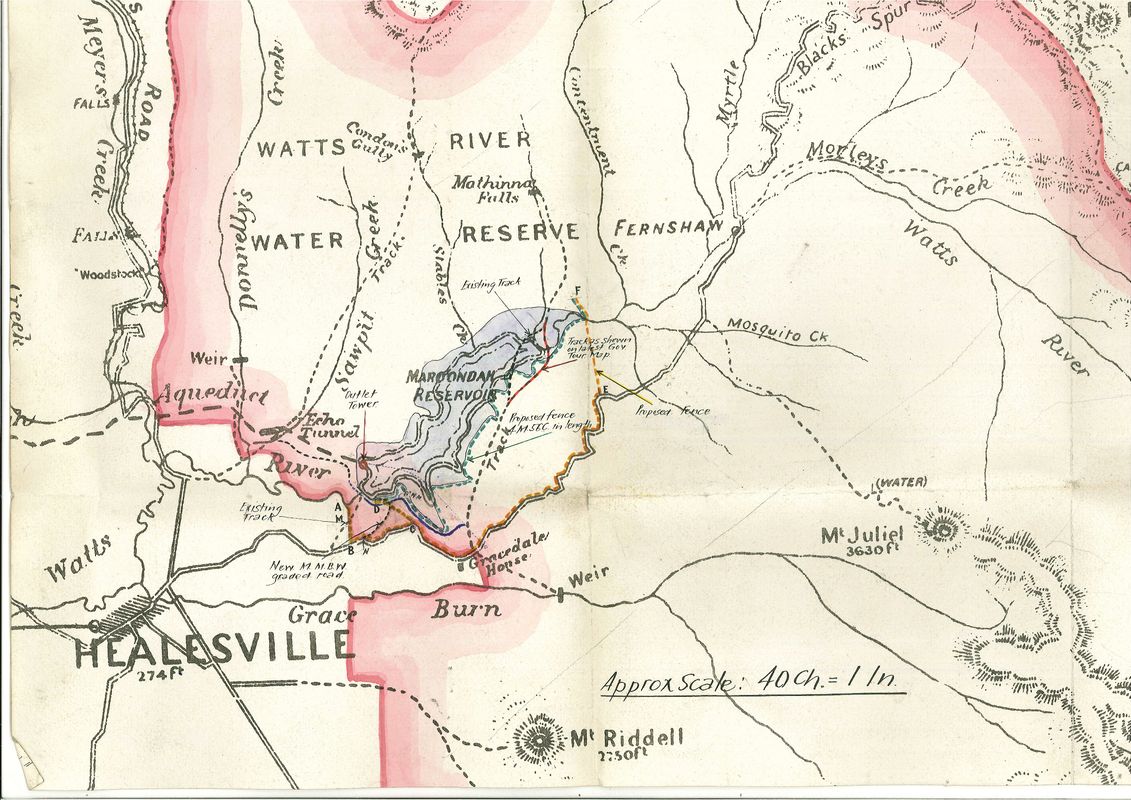

Historic map of Maroondah Reservoir.

Image: Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria

With the dam finished, the MMBW turned its attention to creating an exceptional public park befitting its splendid natural setting. This was particularly challenging as construction works and, in particular, a catastrophic bushfire in 1926 had devastated much of the densely treed land set aside for the public park. To ensure success, the MMBW called upon Hugh Linaker (1872–1938) – senior public servant, tree specialist and one of the most significant landscape designers in Victoria in the early twentieth century – to design and implement a tree-planting scheme for the park in 1927–28.

Despite the devastation, the broad valley floor behind the dam, the rising monolithic structure of the dam wall and the tumbling waterfall of the cascading spillway running into the Watts River – all ringed by the distant hills of the catchment – provided a splendid backdrop for Linaker’s design. Linaker set about replanting “idealized nature” for the visiting public, perhaps reminded of the broad glacial valley, monolithic rock formations, cascading waterfalls and meandering river of California’s Yosemite National Park (with which the area had been compared).

Linaker was a master of creating grand forest landscapes. In his designs, he achieved great visual richness by contrasting qualities of tree species such as form (upright and spreading), foliage (colour, texture and shape), bark (texture and colour), tree origin (exotic and native) and seasonal character (evergreen and deciduous). In tree choices, Linaker drew on a favoured palette of conifers, eucalypts, palms and deciduous species. Where allowed full expression, as occurred at Maroondah, his results were spectacular.

MMBW records reveal that by June 1932, Linaker had supervised the planting of almost six thousand trees and seventy-nine shrubs in both the public park and in the closed catchment area. Linaker’s outstanding tree collection remains largely intact today and is highly significant, both as a collection and for individual specimens of exceptional quality. These include Upright Monterey Cypress ( Cupressus macrocarpa “Fastigiata”), Smooth-barked Apple ( Angophora costata ), Smooth Arizona Cypress ( Cupressus glabra ), Blue or Himalayan Pine ( Pinus wallichiana ), Cork Oak ( Quercus suber ) and Coast Redwood ( Sequoia sempervirens ).

Descending the entry road today, one can see Linaker’s vision for the park fully realized. A rich tapestry of majestic trees, both exotic and native, lies before the visitor. Grassy gentle slopes punctuated with conifers and eucalypts gradually yield to a magical tree-canopied sense of enclosure on the valley floor, along which the Watts River meanders.

Linaker’s tree-planting scheme was soon augmented by hard landscaping elements including steps, retaining walls, paths and shelters made of local stone and timber. In design and choice of construction materials, these elements demonstrate the influence of both the European nineteenth-century naturalistic landscape tradition and the United States’ National Parks Service on interwar landscapes in Victoria.

The purchase of adjoining land in about 1972 extended the area of the park, and today provides visitors with a glimpse of the area’s indigenous vegetation prior to the formation of the reservoir. Throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, the park experienced embellishments and ornamentation typical of their time, but always in a way that was respectful of the spectacular landscape created during the 1920s. Despite the inevitable changes that have occurred over more than eighty years of use, it remains surprisingly intact and continues to be one of the most popular public parks in Victoria.

By creating a splendid recreation area for the public as an integral part of its first closed catchment reservoir, the MMBW was in effect promoting its work throughout the state. Maroondah Reservoir became a powerful advertisement, in living colour, for the MMBW’s ambitious policy. Its immediate and spectacular success was a public relations triumph, and made it the model on which all subsequent MMBW reservoirs have been based.

What was achieved at Maroondah Reservoir was one of the most impressive landscapes ever designed for public purposes in Victoria. The combination of the awe-inspiring mountain scenery, the engineering and architectural masterpiece of the reservoir and Linaker’s grand forest landscape resulted in one of the best examples of a monumental landscape in Victoria.

A comprehensive study of the Maroondah water supply system, undertaken by Context for Melbourne Water in 2010, assessed Maroondah Reservoir as historically, aesthetically, socially and scientifically significant to Victoria. Such places with recognized heritage values pose many challenges for their future care and development. This is especially true of landscapes, which are constantly evolving, and where new uses, plantings and structures may be required in the future.

Looking across the Maroondah Reservoir Park from the dam wall.

Image: Mahfuzul Haque

Those responsible for the parkland at Maroondah Reservoir are currently examining such issues. But there exists a process that assists heritage specialists, landscape architects and managers to understand heritage sites and work together for their future. The process, which results in a comprehensive document known as a conservation management plan, can help chart a course to balance protection of heritage values with future developments. Additionally, it can transform heritage considerations from constraints into sources of inspiration that can be used to create landscape responses of sophistication, nuance and great textural richness. It can also allow heritage consultants and landscape architects to resolve much of the tension inherent in planning for culturally significant sites. For the monumental landscape of Maroondah Reservoir, the creation of a conservation management plan is the essential next step to assuring the future of this magnificent place for generations to come.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 7 Aug 2015

Words:

Lee Andrews

Images:

Courtesy of Parks Victoria,

Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria,

Mahfuzul Haque,

Russell Charters

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2015