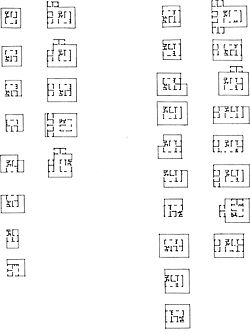

An early example of generative plans for an Aboriginal community housing portfolio, based on self-build staged technology, designed by architect Ken George at Wilcannia, 1976. From Paul Memmott, Humpy, House and Tin Shed (University of Sydney, 1991.) Column 1: Stage 2 variants Column 2: Variants produced by combining Stage 2 plan form with breezeway and double bedroom modules Column 3: Stage 3 variants Column 4: Stage 4 variants

Cultural issues are difficult to address in the supply chain, and are therefore often forgotten. Paul Memmott outlines the accumulated knowledge and suggests that it can form the basis for an improved national procurement strategy.

Aboriginal housing has been on the national political agenda since around 1970. Benchmarks, backlog targets and planning goals have come and gone but the problems are hardly closer to being solved than thirty-eight years ago. Another wave of political rhetoric, finger-pointing and closet-rattling arose in the media in 2007, and policy was set to shift again.

This time last year I was of the view that the Howard Government was repositioning Aboriginal settlement policy back in the 1960s with a form of neo-assimilation that fitted within neo-liberalism. In 2008, with the new Labor Government, I’m concerned Aboriginal settlement policy may be being repositioned back in the Whitlam era of the early 1970s. That is, the new government is trying to solve the problem simply by throwing money at it fast. This won’t solve Aboriginal housing problems either.

The last thirty years have seen a recurring pattern in government responses to Aboriginal housing: so-called “new ideas” are introduced to reduce the capital cost and delivery time, steps which consequently reduce housing standards, increase medium-term running and maintenance costs for residents and lead to premature housing failure as opposed to optimal housing longevity of, say, forty or fifty years plus. (Some of us in cities live in houses that are 120 years old.) In early 2007, members of the Indigenous Housing Taskforce asked some searching questions. Was the wheel (of Aboriginal housing) being rebuilt or reinvented? Were the original problems defined correctly but never properly addressed by successive governments, or have the problems been transformed along with political agendas and the nature of wider society and the global context?

The answer is probably a little bit of both. However, I would like to discuss cultural issues, which are difficult to address in the supply chain and which have been either poorly undertaken by government or rejected as being irrelevant. A number of persistent and critical cultural issues continue to recur in the delivery and performance of housing. Nonetheless, important knowledge has been developed over the last three decades, and this can provide a base on which to build local, regional and jurisdictional approaches.

The issues also need to be understood in the context of three factors: the housing backlog, the complexity of the client groups and the political time cycle.

Housing backlog

National Aboriginal housing backlog surveys and estimates have been done since the early 1970s. The backlog has never been filled or looked like being filled, ever. The shortage in appropriate housing, particularly for Indigenous communities in remote areas, remains to be addressed. Housing shortages lead to stressful crowding which, in turn, exacerbates problems caused by malfunctioning or inadequate health hardware and a lack of regular maintenance. The figures are scary and translate into billions of dollars. For example, the last time I obtained accurate figures on the Northern Territory backlog (in 2003), the assessed need was twenty times what could be provided with the annual Aboriginal housing budget; and there was an ongoing population growth rate of three times the national average.

The consultation with and participation of client groups

At first European contact, there were about two hundred language groups with diverse cultural differences, which had varying degrees of contact over time. Processes of cultural change have varied across the continent, producing even more cultural diversity among contemporary Aboriginal cultural groups. This complexity means it is not possible to generalize precise cultural needs at a national level. Instead, we need ongoing consultation to identify qualitative housing needs. Indigenous groups, and both men and women, need to be able to actively participate in defining needs and in the design and supply of housing. Consultation should support both the traditional owners and the residents who use and own the housing to make the key decisions concerning the housing.

The political cycle

The political time cycle itself causes problems. The housing procurement process – needs assessment, securing of funds, design consultation, documentation, tendering, construction, occupation, implementation of housing management policies and stabilization of tenancies – represents a sequence that always extends beyond the three-year political cycles. We need to find ways to ensure the continuity of this process despite the fact that government policies can change regularly in three-year cycles. How do we make Indigenous housing resistant to the political cycle? By long-term planning? By use of statutory authorities? Or by bipartisan partnership?

So, how might we proceed? What should be considered when developing appropriate, culturally specific approaches to delivering housing for Aboriginal communities? A great deal of skill and specialist knowledge about Aboriginal housing has been built up in a subsection of the architectural profession. This can be characterized in terms of three paradigms – cultural design, environmental health and housing-as-process, which are discussed in detail by my colleague Carroll Go-Sam elsewhere in this issue. I shall draw on this knowledge to address three themes in the delivery of culturally appropriate housing – building community capacity for housing management, developing scales of economy through a portfolio approach and developing scales of economy through regionalizing Aboriginal housing delivery.

Build community capacity for housing management

The first issue is quality. Longevity can only be achieved if good quality housing is supplied in the first place. The life span of a $150,000–$200,000 building (in 2007 dollars) is very short and the function rate low (indeed, the products would not be compliant with industry codes and standards). High-quality design and construction needs to be combined with regular, adequately funded, programmed maintenance. Most Indigenous rental housing is overcrowded and old. However, a growing body of evidence shows that the primary causes of housing failure are poor initial construction or lack of regular routine maintenance (as required in any Australian home). Blaming residents does not address the primary causes of the problem.

It is also vital to build and maintain the capacity of Indigenous communities to manage their own housing and essential infrastructure. Many Indigenous organizations have demonstrated the capacity to deliver and maintain housing services through constantly changing policy regimes. These Indigenous organizations could be even more effective if provided with adequate long-term government support. Poorly resourced community-based maintenance teams with a low level of trade qualifications cannot effectively operate in a privatized industry model of delivery combined with low rentals paid by low-income earners. (We should note here that public rental housing management itself is heavily subsidized by government.) However, Indigenous community housing organizations are currently being wound down in certain states, with responsibility for the management of community housing stock being handed over to state and territory governments. Many see this as a retrograde step. We have only to look at Queensland in early 2008 to see the issues: the government has been unable to electively deliver repairs and maintenance for nurses’ and teachers’ houses in remote communities. I predict Indigenous citizens will fall further to the bottom of the pecking order in terms of housing services. The mainstreaming of housing services by state and territory governments will also adversely affect community capacity building.

Scales of economy – portfolio design

A general problem in housing procurement is selecting the overall design approach for a settlement, community or region. Options include one-off designs for individual clients, repetitive use of a one-off design, a generic design approach (extendable and generative house systems), a portfolio of a limited number of house types, and a large portfolio of diverse types.

A portfolio requires a set of house designs that can work climatically in all orientations in a settlement, along with designs for flat sites and sloping sites (if both occur). It requires house designs with one, two, three, four and even five bedrooms for varying household sizes and types. The portfolio may also need “special needs” designs: single men’s houses, single women’s houses, old people’s houses, large communal or extendable family houses (six bedrooms or more), and houses for people with disabilities.

In all, I would estimate that a regional portfolio should be in the order of fifty to one hundred designs. A portfolio of a limited number of types, as employed by many government departments in the past, fails to satisfy the diversity of user requirements for the differing cultural groups within or across regions.

My ideas on this topic have developed following the analysis of approximately 120 designs in the Tangentyere Design portfolio in 1986–88. There were important lessons to be gained from the Tangentyere experience. A skilled process of consultation involves tours of existing houses for prospective clients. Often this leads fairly quickly to clients identifying and selecting already-existing designs as being appropriate for their needs. At the same time, the architect consults with individual clients to identify their specific needs and to determine if the design they have chosen requires amendment or modification. In some cases, there is of course no suitable design available and the architect will commence from first principles and develop a special one-off design. But this in turn adds to the portfolio of designs. Before using a design again, Tangentyere staff obtained feedback from users on the performance of the house.

Coupled with this process was a management approach that aimed to capitalize on the potential of individually designed houses to assist in the stabilization of tenancies, which increases educational and employment prospects. This is based on the argument that client participation in design results in a strong identity with the house and leads to an attitude of care and responsibility.

However, designing a house for a specific client cannot prevent the possibility of that client becoming obliged to leave that house. The strength of traditional Aboriginal cultural values in certain parts of Australia means that the value placed on a house is not likely to supersede the importance of observing customary law following a death. Other types of social problems and pressures can also result in a family abandoning a house. These problems require social planning with an aim to introduce appropriate environmental changes, leadership training and support, and educational programs that will assist in socially stabilizing communities and their tenancies.

There was, therefore, an important implicit strength in how the one-off design process was used at Tangentyere. Each time an architect carried out a process of consultation, brief preparation and translation into design, the architectural result, if carried out competently, contributed to a broader statement of communal design needs in itself. In this way, the Tangentyere portfolio represented a composite statement of design needs for all the Alice Springs town camps, made up of over 130 individual statements as assessed by five or more architects over ten years. There was, therefore, no real dilemma between the one-off design process and optimum economy, because at the centre of the problem is the difficulty of establishing an objective definition of Aboriginal needs in housing and translating it into a suitable portfolio of design.

Housing for changing user needs

Even when a suitable housing portfolio is operational, housing needs will not remain static from generation to generation. It is important to design for changing Indigenous user needs. Houses need to be able to be easily renovated in response to shifting spatial and hardware needs. These might include changing spatial needs arising from increases (or decreases) in household sizes or from dissatisfaction with spatial planning due to cognitive shifts in house constructs or architectural values. The self-definition of needs can occur through ongoing experiences of housing. Geoff Shaw of Tangentyere Council talks of “families growing into houses.” This implies a symbiotic process of adjustment between household character and house design, as household needs are redefined and transformed during residence.

The basic principles of housing design for future architectural change are well known, of course. They include such strategies as ensuring ablution facilities are not poorly located in plan (thereby preventing extensions), using a proportion of non-structural walls to facilitate changing room layouts, ensuring verandah areas can be readily built in as rooms and designing roof forms, rakes and ceiling heights to allow extension in desirable directions. Indigenous community housing organizations also need access to appropriate resources (agencies, funds, tradespeople, tools, materials et cetera) to ensure that their new houses are designed to facilitate future ease of extension.

Scales of economy – regionalizing Aboriginal housing delivery

What is the best scale for delivering housing service programs? From centralized government or from local community? Or is there a middle ground, at a regional level? Given the issues of cultural variation across the continent, my preferred approach is to strengthen regional delivery systems through stable Indigenous housing organizations.

One of the more difficult problems is the coordination of all the relevant bureaucracies in a combined plan of action. For an Indigenous community housing organization, the best approach is to incorporate or at least coordinate as many functions as possible within its own organization. This means coordination can be centralized as much as possible. However, it may be in direct contrast to trends in government jurisdictions that promote the mainstreaming and decentralization of welfare services among different agencies. This multiplies the number of organizations Aboriginal people have to deal with and the accompanying communication and coordination difficulties.

One problem with the regional model is assessing the optimum size and scale of operation of such an organization. If it is too big, with too broad a geographic range and too large a bureaucracy, it is likely to weaken its grassroots contact and support. On the other hand, if a strong management base is required with adequate resources, running costs necessitate that its services be spread as widely as possible.

A meaningful starting point for the design of housing service delivery is an understanding of contemporary Aboriginal mobility regions or sociogeographic regions, a phenomenon documented consistently since the 1960s by anthropologists and geographers. One merit of such a regional approach is that housing needs appear fairly similar across the communities of the region, due to a similar cultural background, pattern of cultural change and history of settlement experiences. Hence the process of providing architectural solutions should, predictably, after an initial period of in-depth consultation and individually prepared designs, result in a portfolio of houses that is suitable for most of the needs of the cultural region for the immediate future.

Conclusion – culturally specific approaches

A general consensus emerged from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous attendees at the Which Way? conference that current Indigenous housing conditions are unacceptable and, if anything, are set to deteriorate further. We need an approach to delivery and performance of housing that is premised on longevity of housing stock, cultural fit of design to lifestyle and the physical and mental health and wellbeing of households – one that builds rather than undermines human capacity and social capital in communities.

There was wide support at the conference for immediate moves by government to ensure that seventy-five percent of current defective housing be rectified within the coming three years. There was consensus that this was an achievable task, using a commonsense, hands-on approach to basic maintenance issues, and that the current situation of poor health linked to poor housing is avoidable. In addition, new rental housing for Indigenous communities should be appropriately designed for the traditional and cultural practices of the occupants and their communities as well as for particular geographic and climatic conditions. Rental housing must be designed and built to ensure ease of maintenance, low running costs for residents and adaptability for sustainable usage across generations.

Throwing government money quickly into the housing industry will not readily solve Aboriginal housing problems, but we do have the building blocks for an improved national procurement strategy. A lot of work remains in order to build a strategy that will have a stable, nationwide, longitudinal capacity to deliver culturally appropriate designs with culturally appropriate management systems across political time frames and across generations.

At the time of writing, the Northern Territory Government was about to employ “alliance” tendering in a large-scale housing program – the first time this method will have been used in the Aboriginal housing sector. Hopefully it will include a post-occupancy evaluation to determine which of the many necessary goals can be achieved using this new procurement approach.

Paul Memmott is Professor and Director of the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre at the University of Queensland. He is the chair of the Australian Institute of Architects’ Indigenous Housing Taskforce and was one of the convenors of the Which Way? Directions in Indigenous Housing Conference.