Andrew Mackenzie: Being a partner of a global practice presents an interesting dilemma. Clearly there is a shared approach between offices, yet there are also subtle differences. How would you define the differences between the OMA Hong Kong and OMA Rotterdam?

David Gianotten, head of OMA Asia Pacific.

Image: Andrew Tang

David Gianotten: There are things that are very similar, and things that are very different – one of the key things is the way we address clients. Clients in Asia are extremely demanding and very direct. In America and Europe you always work with project managers and client reps; here in Asia, when we meet with our clients, they are the top bosses, so their decision stands.

What that means for the design process is that we need to make very focused efforts, more so than in Rotterdam where there is more space for exploration. Here we explore in the very beginning, but then we need to develop and never allow ourselves to go into the experimental phase again. The feedback we get also represents a very interesting difference. In Rotterdam, the client rep will say ‘good’, but you never know. In Hong Kong we know immediately which direction we should go in, or if a client has a difficult idea we don’t agree with, we know what to address.

AM: I assume that means you have to be that much more careful in how you describe something. If you’re working with intermediaries who have professional experience, they at least understand that you’re presenting in broad brushstrokes, whereas with a client without that experience there might be an expectation that what you present, by way of computer renders for example, is [literally] what will be built…

DG: It can be a virtue that some of them are not professionally experienced, because they allow themselves a broader vision. On the other hand, they also sometimes make decisions for other than architectural reasons – because of spectacle and nothing else, for example. Sometimes that is hard to deal with. Of course, we can do all kinds of things in sketches and models, but then we have to realize it in a building of 400,000 square metres. These are the kind of numbers we’re dealing with – the biggest building in the Netherlands is 180,000 square metres, which for us here is a normal-sized building!

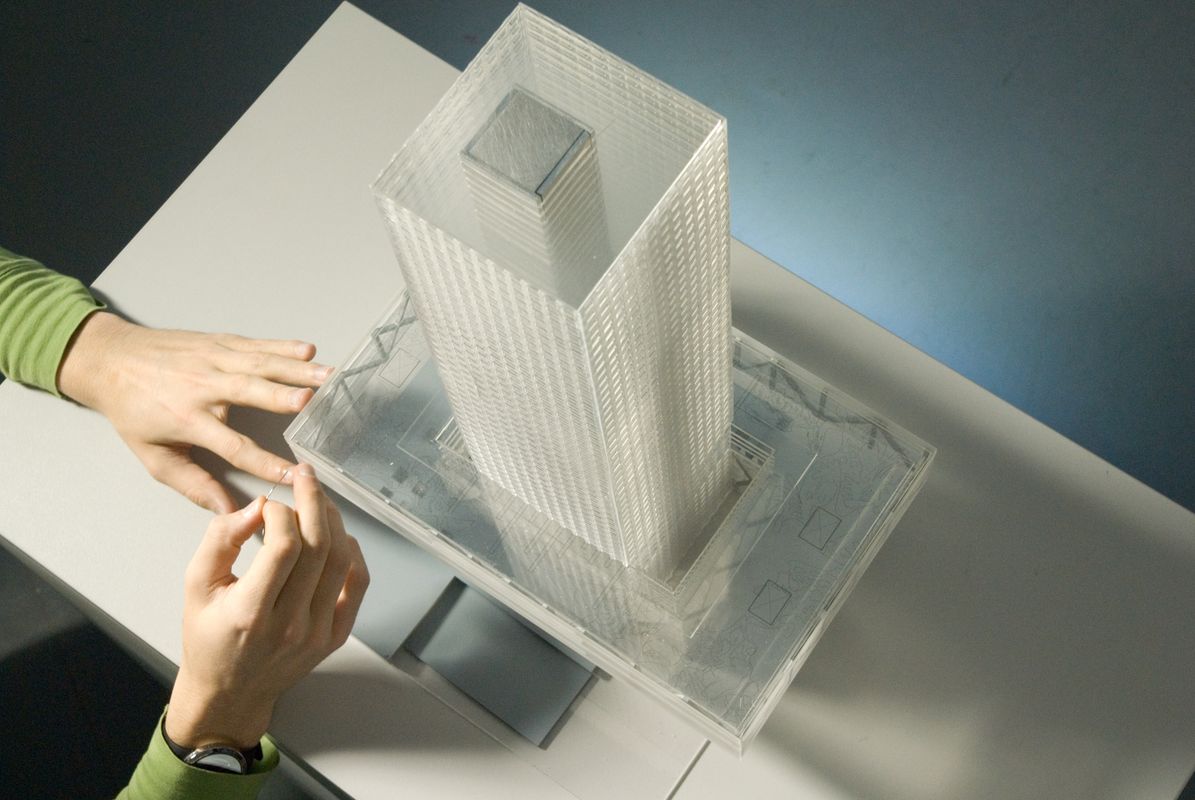

Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

Image: Philippe Ruault

The other big difference is that I’m here as partner-in-charge. I set up the [Hong Kong] office, but I’m not that long in OMA, I joined only one-and-a-half years before I moved here. What that allowed us to do was experiment a little and reconfigure some of the thinking OMA had as a reflex. When I first came to this office, the teams would present fifty or sixty different options but without any context to the project, and it became a picking exercise. Rem was literally going: “I like this one, I like that one.” That, in my opinion, cannot be the starting point of a serious design process; there should be an exchange of argument, then of course the options. So in Asia, we seldom work with more than three to five options in a design process. Rem was also happy with this change, because he was becoming more a judge than an architect.

AM: Was that somewhat replicating Rem’s early experience? The early houses had hundreds of models…

DG: Then it had a purpose, but when the economy was so good it started to turn into making a hundred items and selecting the nicest one, while architecture of course is something totally different.

AM: How did you go about establishing the business and networks in Asia?

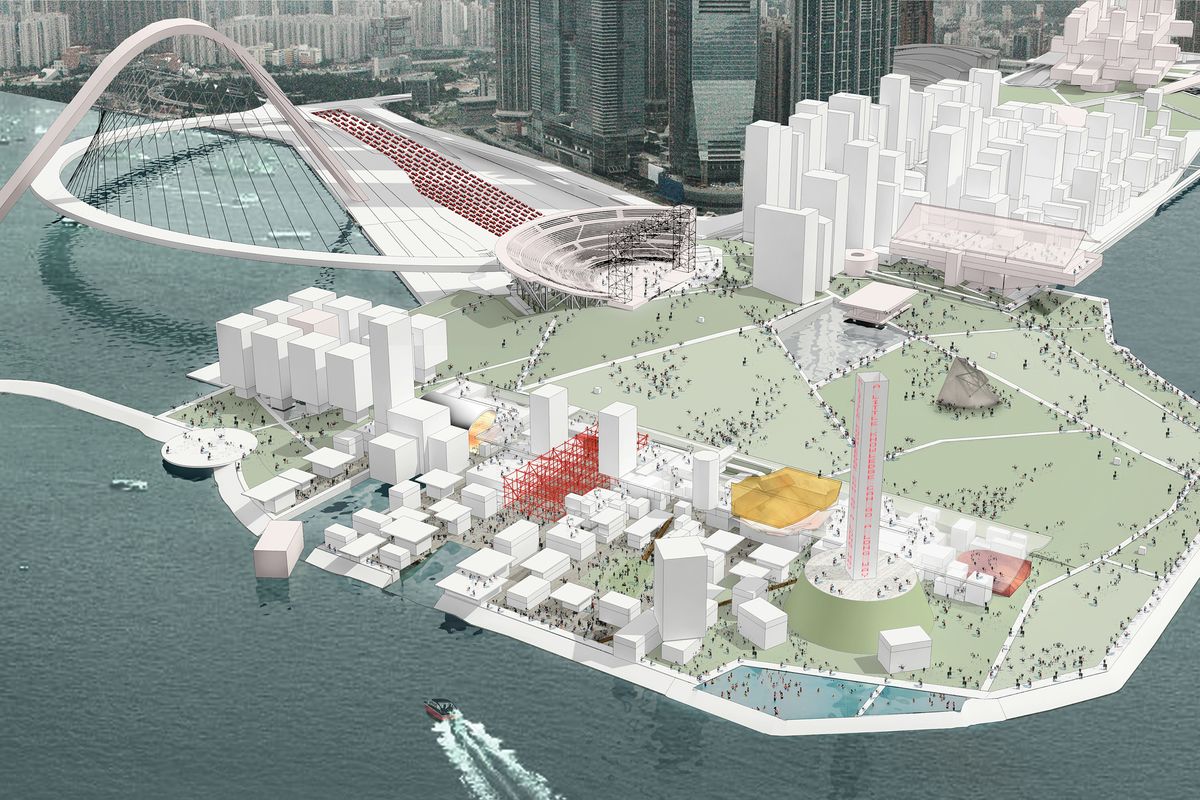

DG: Firstly, we had the West Kowloon Cultural District, which was an important cultural project as a starting point. We had the Shenzhen Stock Exchange that [OMA associate] Michael Kokora and I had been working on from Europe, and we had the Taipei Performing Arts Centre, which was a very important cultural building in the portfolio of OMA overall. So from the beginning we were a Greater China office, you could say. What we also did was cut the geographic area of Asia into four pieces in light of research we did on cultural sectors, relationships, languages, GDP etc.

Taipei Performing Arts Centre.

Image: Courtesy OMA

These four territories included Greater China, Korea and Japan, South East Asia and everything below. Initially we held off Australia as we felt we needed more background. Some parts of South East Asia are still very difficult for international architects to work in because of legislation that only allows you to be an advisor, not lead architect. So we decided not to target those countries initially as we like to have the capacity to make the decisions. Then Greater China exploded in our portfolio, so the second decision we made was to have a much larger presence of Chinese architects. Dealing with China is very specific, you need people from there.

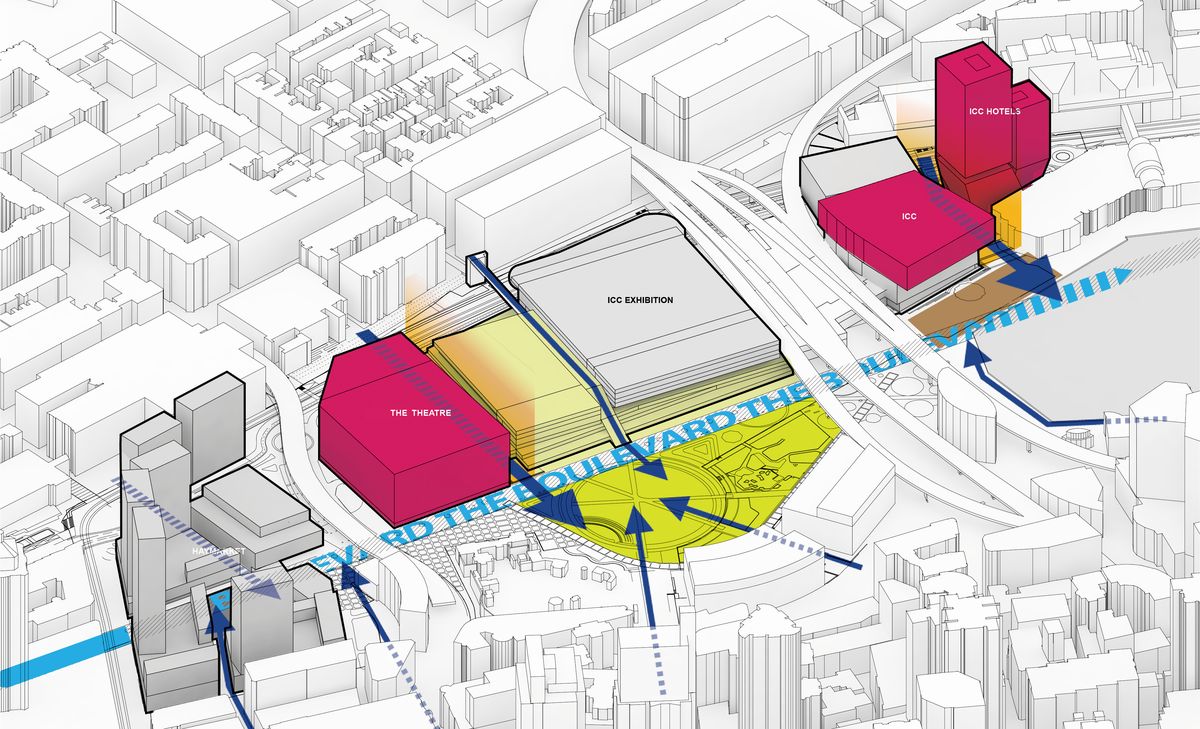

South East Asia started to hold more potential after two years, partly because our networks expanded and partly because legislation started to change in Thailand and Vietnam. Once we had some projects in South East Asia we decided to take the leap and try Australia. We worked with Lend Lease in Sydney at Darling Harbour, which was a mixed success; we won the competition but it sometimes was a clash of two cultural approaches. After that we also worked on a competition for Monash University with Timothy Hill in Melbourne, where we were shortlisted but didn’t win. We made ourselves visible, and we’re still exploring our opportunities, especially now that Paul Jones [formerly of Donovan Hill] has joined our senior team from Australia.

So the vision, to work in parts, and work differently on each part of the region, prioritizing one above the others, has worked.

Sydney International Convention, Exhibition and Entertainment Precinct (SICEEP).

AM: Historically with OMA, whenever a large project comes out of a place, there’s always cultural engagement with that place, not just a building. A lot of practices just fly-in, fly-out – OMA has a reputation for thinking and publishing about the economy, the culture, where it’s going, where it’s come from.

DG: I think that is also a very successful part of this office. I am here as a partner, I have full decision powers on everything; I don’t need to report back to a design board in Rotterdam for a final decision. For many clients, that’s very attractive as our competitors are organized with design boards and their branch offices have limited decision-making power. With clients who are very direct here, they want to go fast, they want to say yes or no, and they expect you to do the same.

AM: That structure of the ‘branch office’ in Asia obviously betrays a particular attitude that is almost colonial. To reverse that attitude, what can Europe learn from China?

DG: I did a few lectures a year ago that were called ‘Speed in Architecture.’ To realize something, the momentum off the project is extremely important in that the speed actually helps. People could learn to make a decision and never go back. Firstly, people don’t make a decision, or when a decision is made it’s going to be tested 15 times. You always end up with a compromise, because the original decision is always different from the decision that results from 15 rounds of testing. In the end, the project is really influenced by that process. What we see is that when a decision is made and people stick with it, there is a much steeper development curve in the projects. I think especially at the moment with the financial crisis in Europe and the United States, people just don’t know anymore how to create that curve, how to initiate action again.

The funny thing is, that speed is not at the expense of people being able to express themselves; a lot of people in the West think that in China when a decision is taken, not everybody is involved, only the leader, but it’s totally the contrary. On the table in a meeting there are sometimes up to sixty people, from every layer in the organization; they all give you their opinion and in the end, the leader summarizes and a decision is taken, in consensus. That is a very interesting process, because it means that everybody understands why the development is as it is. In Europe or the United States at this time, people are following orders that are really the result of bureaucratic procedures, therefore excellence has become extremely rare.

Another thing is the project management models are so complicated in the West these days, it really compromises the outcome of a project for everybody involved. Here, things are kept relatively simple and very open, so people are able to give input to the process – we’re not doing the process because it’s prescribed, but because the project needs a certain process, and you can always change it when the circumstances call for it. That flexibility is also something Europe and the United States can learn.

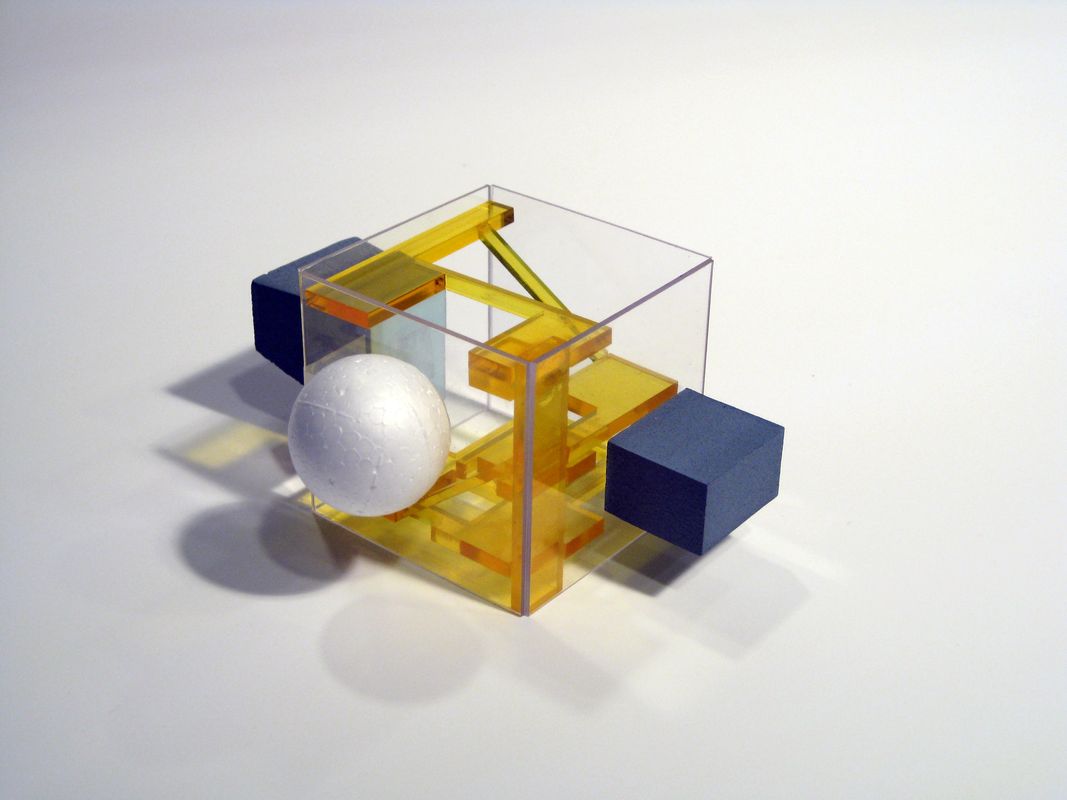

AM: The practice has traditionally relied very heavily on physical models. What are your thoughts about their importance?

DG: For me, very important, because I’m trained in the old way where we did everything by hand, the computer was supporting. We have a model builder that has a team that only works for us. We make models from the very early stage of a design and continue that over its course, from the smallest detail to the overview. No matter how big a building is I always carry a small model if it in my bag so I can touch it, feel it, before presentations.

Models are important to not only understanding the building, but to conveying the message. What you see in our portfolio in Asia is that many of our designs rely on a maximum of three moves, in the architectural and functional planning, and to explain these well you need to have some physical substance. As I’ve said, very often clients don’t read drawings and clients always respond well to the model, much better than any drawing.

The other reason is it’s important to represent the context of a building well. One of the key elements of my approach to design is that we are extremely contextually oriented. Because of the huge scale and ambition of some of our projects, you need to make sure they fit in with their surroundings. In Europe there are plans that cater for that, your maximum height and so forth are set from a governmental level. Here that very often doesn’t exist.

The three villages of West Kowloon Cultural District.

Image: Courtesy OMA

AM: In Australia the dominant paradigm is of small design-focused practices and large commercial practices, with very little in between. It seems that OMA wants it both ways; to be creatively and commercially engaged in the nature of practice.

DG: I don’t have any faith in architectural organizations that can’t control the project from beginning to end and be able to do whatever is necessary in all the phases. We are always intermingled with the boundaries [of practice]; the boundaries are where the excitement happens. If you don’t understand what is within other people’s expertise, you will never be able to make innovative proposals. You need to in-source a lot of idea-making, not only on a design level but on an engineering level, an image level, a contract level, and a PR level. In Asia we have all these layers in-house.

AM: What aspects of working in Europe do you miss?

DG: I miss the fact that you can work on projects that don’t need to have a built outcome, so the research part. Here, research is fully targeted to delivery. All our AMO [OMA’s research arm] projects here are paid projects. Now in Rotterdam that’s not the case.

AM: How do you decide what an OMA project is and what an AMO project is?

DG: We have five guiding terms. To give you an example, AMO is non-physical, OMA is physical. I’m not going to tell you all of them, because that is one of our secrets! It is very attractive to some clients because they cannot predict the outcome, and it’s the adventure they are after.

AM: What opportunities do you see in Australia for OMA?

DG: Our value in Australia could be that we approach our projects without presets. Australia for us is still an experiment. I think it’s an important territory, however, in my opinion the architecture world there, with the exception of a few, is stuck because of the entanglement with their clients. The clients in Australia are really powerful and don’t really allow for any response other than what they are expecting to get. To find a client who is willing to not have a preset outcome for the collaboration is probably more difficult.

We don’t service in the way other large Australian practices do. We service by pushing the idea and that’s a very different way of serving. Clients have to get used to it. They want to control every little step of the project, which you can read in the outcomes. This needs a realization on the client-side. I think OMA can definitely add something if we are given the opportunity to show that our process can lead to a responsible, good outcome, but one that’s slightly more adventurous.

There are so many circumstances that could lead to very interesting dialogue. It’s not the architectural profession that’s going to change things, it’s not the clientele – a public discussion is more important. It’s about creating more of a critical attitude to the possibilities Australia would have if it did things differently.

David Gianotten will give a keynote talk on workplaces across the globe at the 2014 Work Place/Work Life conference. See the full program and purchase tickets here.