Photos David Moore.

The bush around David Moore’s Lobster Bay house is thick with angophoras. These wildly contorted and intensely sensual trees invite comparisons with a photographic series of nudes which Moore began after he moved into the house. In these works he approached the body in the same way as he approached landscape, treating it as a living changing landscape that related directly to the forms of the angophoras and the eroded, shoreline rocks.

Concealed in the angophoras, the house is difficult to find. It sits isolated, astride a bony ridge, in the shadow of a hill named Top Rock. The house was intended as an isolated retreat. Following the break-up of his marriage, Moore wanted somewhere tranquil and peaceful where he could take his four children on weekends, which was less trouble than camping, and which was near the bush, so he could go bushwalking.

For convenience, it also had to be less than two hours from Sydney.

Moore acquired the site on Highview Road at Pretty Beach in December 1968.

On the western edge of Bouddi National Park, occupying the north slope of the ridge, it has wonderful views of Brisbane Water, Ocean Beach and Pearl Beach. In addition to the magnificent angophoras, the site had rock outcrops covered with scattered lichen. Moore recalls that he “didn’t want the house to interfere with the landscape”. He considered the land to be more precious than anything that might be built on it.

Ian McKay’s first scheme went out the window fairly quickly. The second, an irregular wing which hooked onto and curled around a large rock outcrop on the ridge, didn’t fare much better. McKay was struggling to come up with a suitable scheme. In discussions, Moore said he wanted the house to sit like an insect. At this point Moore went away to think. He then made his own sketch which became the foundation for McKay’s third design.

Moore’s proposal was for a roughly symmetrical building centred around the living space with kitchen behind, master bedroom on one side, bunk rooms attached to the opposite side, and the entry between them. McKay found this “very interesting”.

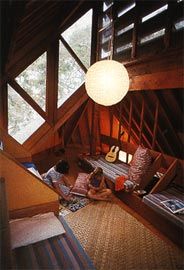

He modified it by stacking the bunk room over the living area, making the house perfectly symmetrical and more vertical.

McKay introduced two standard timber trusses propped up in an “A” by rafter beams. At its top, the vertical face of the truss above the opposing rafters was exposed to let sunlight into the upper bunkroom through horizontal louvres. To this basic A-frame foundation, McKay added wing roofs on each side to cover the two bedrooms. The resulting pyramid shape is like a bird, but it also resembles a tent pitched with its guy ropes stretched wide from the central support.

The house took nearly four years from start to finish. The design and the drawings were completed in September 1969. The builder, Peter Velling, did not start till March 1971 and the job was completed and occupied in June 1972. The total cost was $27,524, including $2,632 in PC items.

This figure seems astonishing when compared to today’s inflated costs. The bearers and rafters were made of sawn Oregon lightly sanded, with 3/16” plywood for ceiling and walls, and a Super-Six A/C roof. The Oregon has weathered to a satisfying grey and now blends with the surrounding angophoras, small blood woods, and coastal banksias.

While the house feels like a tent inside, its unity is complicated by the upper sleeping level overlooking the main living area. The simplicity of tent living is echoed by the placement of the deck next to the living space facing west for the afternoon sun. The bunk room is snug and cave like with views out through the trusses on each side and down over the living area. This creates a wonderful connection between children and adults and moves the space vertically. The ladder up to the bunk room provides one of the most arresting details.

This challenging piece of climbing apparatus is made of individual timber foot pads mounted on a metal pipe. McKay also designed a fireplace, with the chimney flue on the diagonal following the ceiling slope. However the fire smoked and people cracked their heads on the hot flue, so it was replaced by a more practical vertical flue and a Canadian fireplace design passed to Moore by Colin Madigan.

The Moore House is obliquely Wrightian, yet it also departs from Wright’s dicta in significant ways. It is very Australian in its reticence, and sits lightly on the bulging rock shelf. And, whereas Wright often extended a wall past the roof eaves so that his houses appear to reach out symbolically into the landscape, McKay takes his architectural cues from the landscape. This is a crucial difference.

Where Wright starts with the “manmade” and acknowledges nature outside it, McKay allows the outside to work its way into the house. The Moore House nestles on the rock much in the way a bird might choose to build its nest.

Moore spent 15 years eradicating the lantana and bitou bush and getting the land in shape. He also thinned the bush as a precaution against the fires which threatened the house on two or three occasions. However, after more than 20 years, Moore’s familiarity with the site grew to the stage where it no longer offered him surprises and he felt a need to move on.

His children rebelled, insisting he keep the house. This passing down of the Lobster Bay house will add a new stratum of knowledge to it.

The Moore house is a thoroughly Australian masterpiece, because, while it is subtly Wrightian, there is no obvious literal borrowing and no noticeable quotations.

Moore came from an architectural family (his father was the famous architect and painter, John D. Moore, and his brother Tony was also an architect) and he was accustomed to exploring architecture through his photography. He possesses a critical architectural intelligence that at times placed great demands on McKay.

This has resulted in an exceptional work, inspired by the contorted structuralism and gestures of angophoras (that most human of Australian trees), the bulging rock outcrops, and the spirit of the bush itself.

The Moore House is about the transient occupation of the land, about camping and the bush. It derives its special outlook from a consideration of bushwalking as personified by the late Milo Dunphy. Non- Aboriginal occupation of Australia has been so brief, and as new arrivals we need to discover the bush so we can become more than mere sojourners.

Moore saw himself as having a custodial role for the land. This is embodied in the house, in the way that it rests lightly on the rock, and to the degree that it is a catalyst for the discovery of its surrounding.

Moore recalled later that he found new meaning through photographing the rocks and trees, the beaches and the ocean. The bush, with its subtle seasonal changes, gently affected his photographs, which are lyrical as a result.

Philip Drew is Sydney-based architectural critic and author