Researchers at the University of Melbourne are currently undertaking a three-year study of twentieth century school design in Australia. The group’s research is focused on innovations in planning and architectural expression that accompanied new approaches to teaching both primary and secondary school children. Researchers are contextualizing Australian developments by comparing them with those in North America and Europe during the same period. In addition, the project is looking carefully at the scope of heritage protection for important modern educational buildings. In November 2012, the group is hosting a workshop to highlight the heritage and conservation issues presently confronting schools and university campuses. The event will include public lectures by leading international conservation practitioners David Fixler and John Allan.

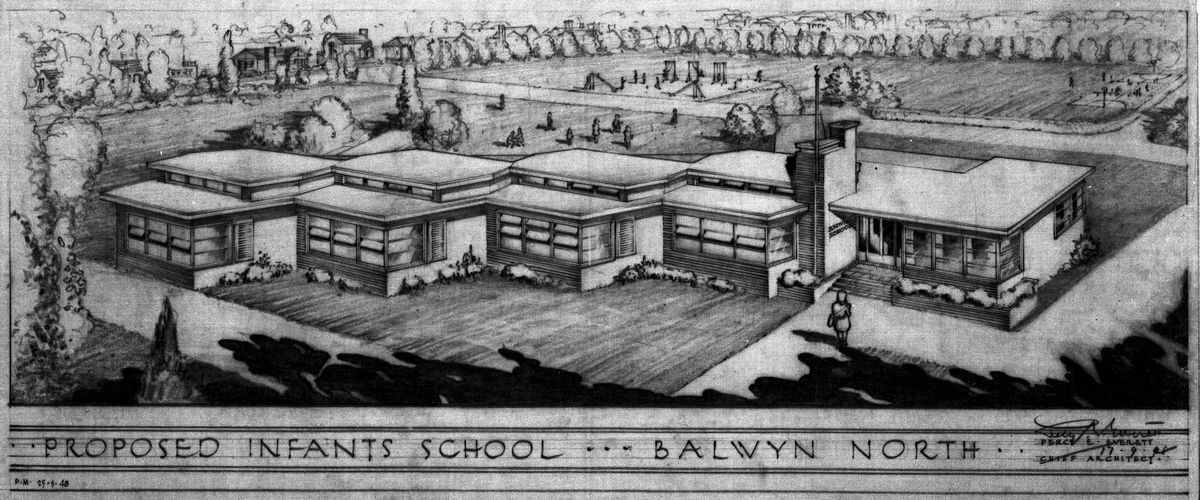

In the twentieth century, Australian educators, taking their lead from progressive thinkers such as John Dewey and Maria Montessori, encouraged a more student-centred approach to schooling, which involved greater freedom of movement for pupils and also demanded greater flexibility of teaching spaces. Designers sought continued improvement in the environmental conditions of schools through lighting, ventilation and acoustics and, in later years, through greater attention to the landscape qualities of sites. Yet for much of the century public works departments and state education systems struggled to keep up with growing demand for new facilities. Not only did they face rapid growth in population, especially in the proliferating postwar suburbs, they also grappled with expanding entitlements and expectations as secondary education shifted from being a preparation for university to a universal entitlement.

In NSW in the postwar decades, the Government Architect’s Branch struggled to reconcile these competing demands. Perhaps the most significant shift in thinking in the period was led by Michael Dysart. In the period between 1959, when he developed designs for the Belmont Primary School and the hospital school at the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children, until 1966, when the new high school at Pennant Hills opened, he accomplished a transformation in the way the GAB approached school design.

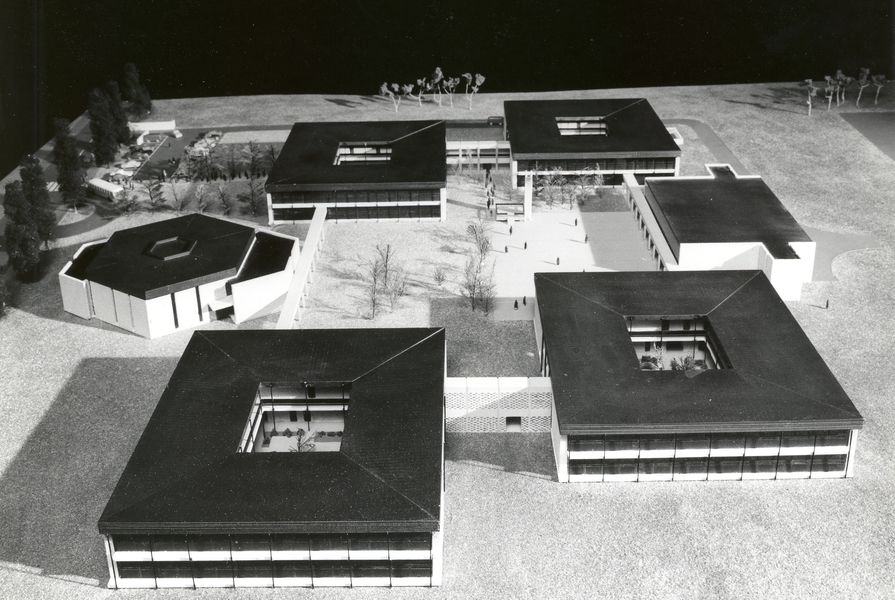

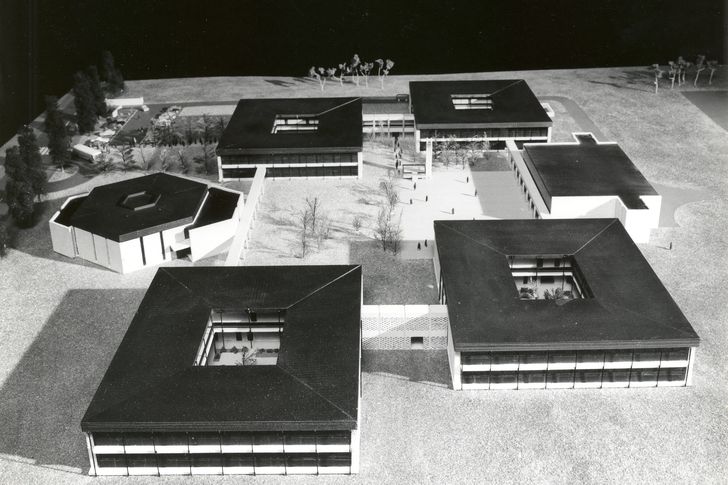

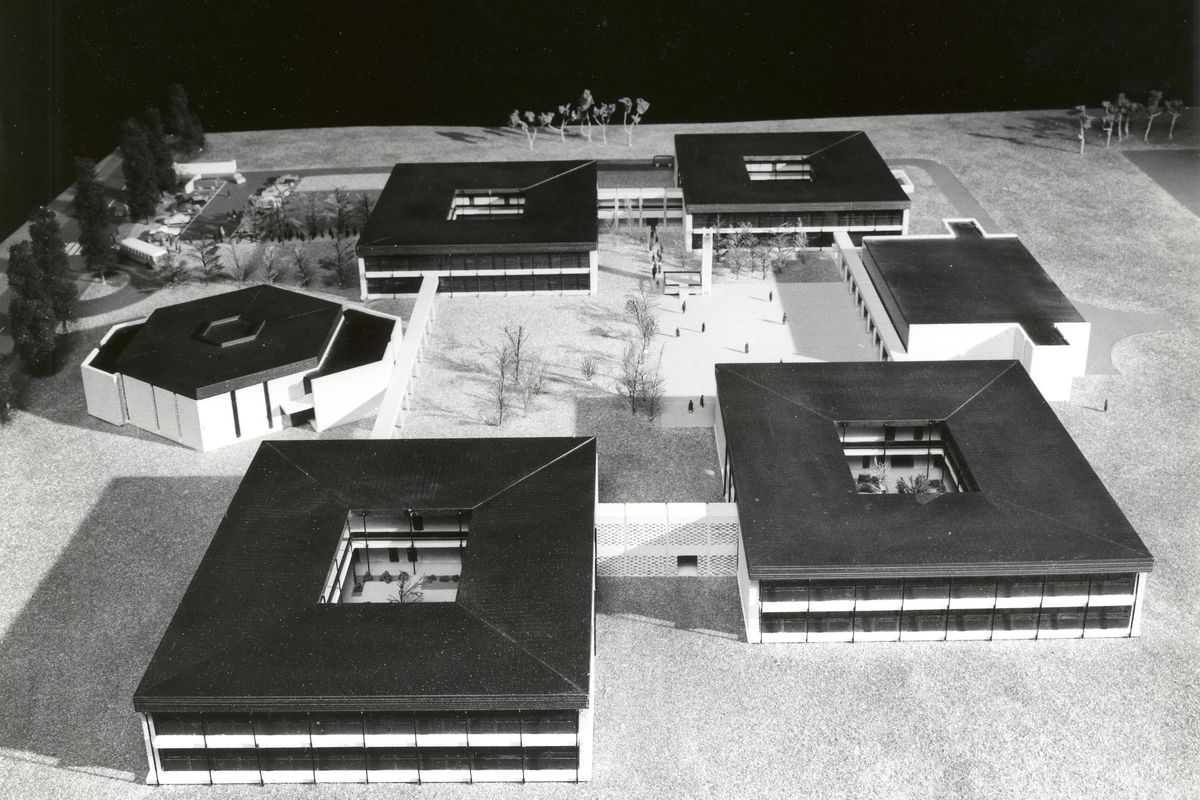

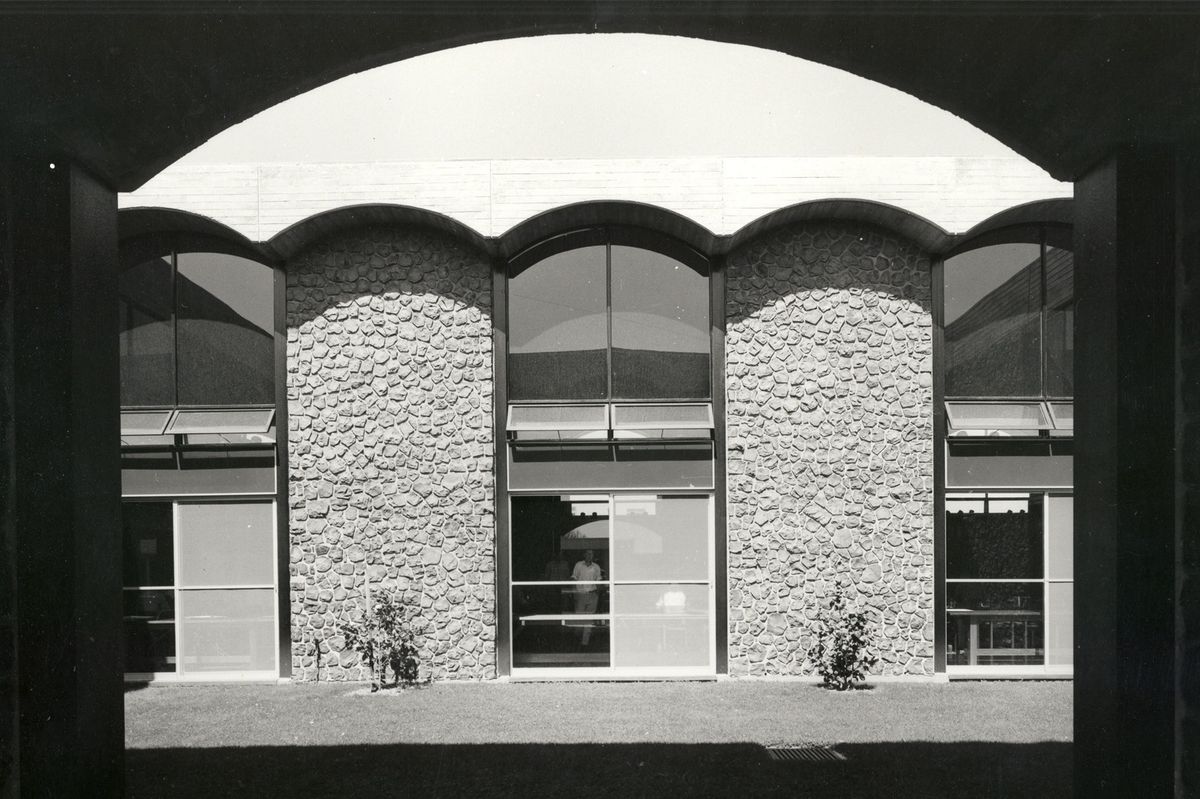

Undated photograph of a model of the doughnut schools designed by Michael Dysart, NSW Government Architect’s Branch.

Image: Max Dupain , AIA NSW Dupain Collection

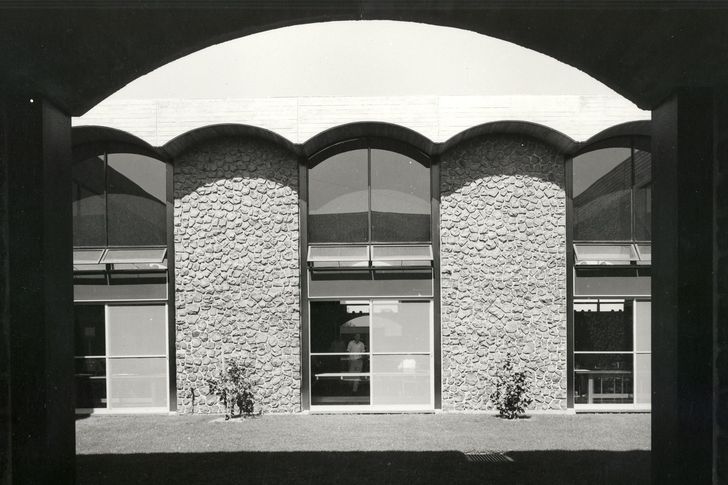

The Dysart schools from this period were innovative in two main ways. As with leading European and North American architects who designed innovative schools in the period such as Arne Jacobsen, Hans Scharoun, Denys Lasdun and Caudill Rowlett Scott (CRS), Dysart moved away from simple linear blocks or finger planned schools, which were typical in the postwar years. In their place he employed a series of square doughnuts in a sort of pinwheel configuration around a large central space. He usually placed a rostrum and bell tower – which sometimes also doubled as an incinerator – in that central space, which could then be used as an all-of-school gathering area. The scheme did away with indoor hallways and replaced them with covered walkways and cloisters. The second innovation was a novel construction process which enabled the erection of a structurally independent roof very early in the process. This allowed work to go on regardless of weather and proved to be a significant efficiency. By these means Dysart provided a new sense of refuge and place definition in the school environment while also devising an efficient system for delivering school buildings. While there was a general move towards ‘demonumentalizing’ school buildings in the postwar decades, the Dysart-designed schools introduced a different set of spatial relationships, one which recalled the deeper traditions of communities of learning.

Under threat Robb College, University of New England, 1960-1964. Architect: NSW Government Architect’s Branch (Michael Dysart).

Image: Max Dupain

It is important not only to recognize these innovations, but also to retain where possible some of the best examples. Interesting variations on the basic pattern such as the Malvina St High School in Ryde and well maintained standard versions such as Miller Technology High School are worthy of recognition and some level of heritage protection. There are challenges involved in effective conservation of school buildings not least of which is a broad obligation to avoid imposing new constraints and burdens on school communities. At the same time, acknowledgement of the significance of these schools and careful conservation is a very good way of fostering pride in them. In this period of tight funding constraints and ongoing attacks on the public sector such a show of support for the great legacy of twentieth century public schooling is much needed.

First published in Architecture Bulletin Nov/Dec 2012.

Classroom to Campus Symposium.