The scene set by this exhibition is of a serene Victoria enjoying her postwar prosperity, along with the pleasures of a bayside leisure lifestyle. This is an age in which the Victorian citizen, the everyman, can feel sure of his place in the workaday world, and then return home to large helpings of meat and three veg prepared by the wife. There persists, more or less imperceptibly, the quiet murmur of a fading Indigenous race, whose children and land have been stolen; but little matter, this is now a resolutely white Australia.

Whiteness has been so thoroughly internalized in the nation’s psyche that the White Australia Policy has been cautiously allowed to ease. Even with the considerable postwar push for immigration – populate or perish – the newcomers are mostly European, and the newsreels show images of smiling blonde women and smart, healthy young men in stylish sunglasses alighting from large ocean liners. There are dams to be built and primary and secondary industries to consider. Television is just being introduced into the mainstream and all the living room picture windows, one by one, up and down the block, begin to flicker and glow after dinnertime as families gather around the televisual hearth to hear news from elsewhere.

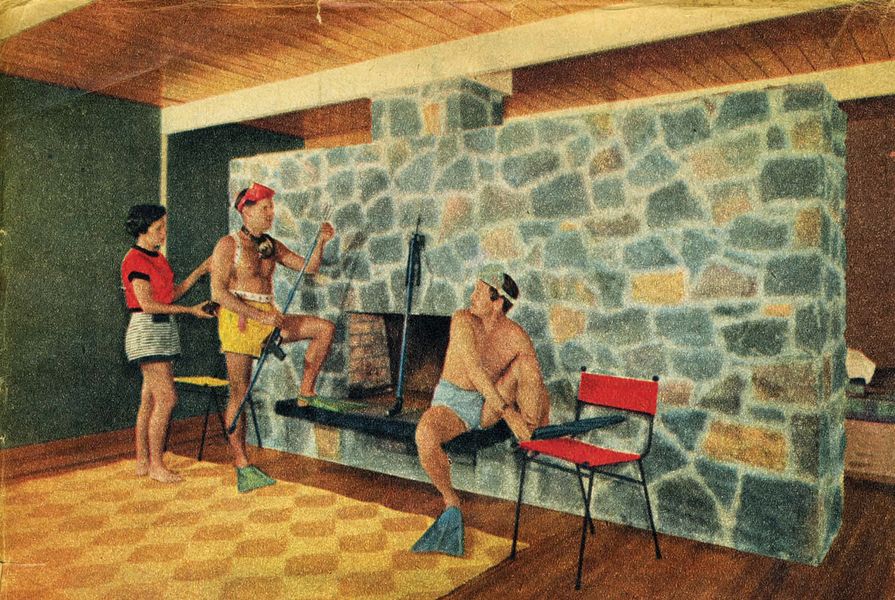

Interior, Rothel House by Chancellor and Patrick.

It is during this period, from the early to mid 1950s, that experimental young Australian practices such as Chancellor and Patrick look with great admiration toward the new architecture emerging out of Europe and the international flowering of modernism. As an architecture student, David Chancellor collects books by Bauhaus architect László Moholy-Nagy and he also purchases a copy of Alfred Roth’s The New Architecture.

At the Mornington Peninsula Gallery, in an exhibition display case, on a page strategically opened, there can be witnessed a line-up of what have become the icons of modernism, the money shots, from Corb’s Villa Savoye to Mies’s house in Brno and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bear Run (or Fallingwater). The desire for these pure expressions of form is almost visceral, albeit still in black and white and coloured with a yearning nostalgia for a possible future. No unnecessary excess, truth in materials, an honesty of form.

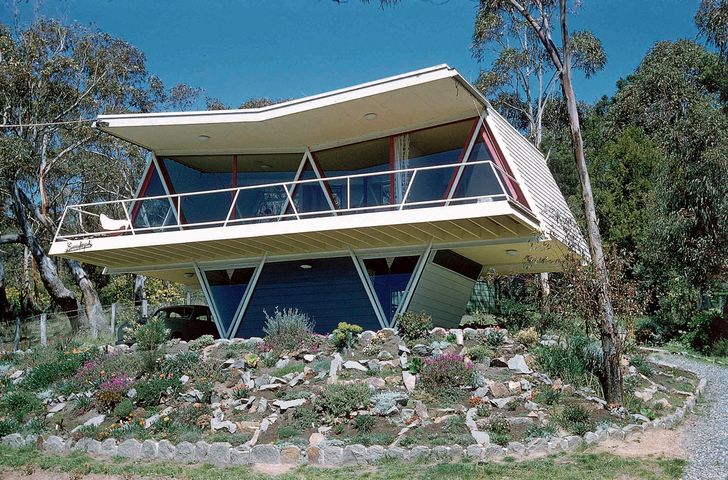

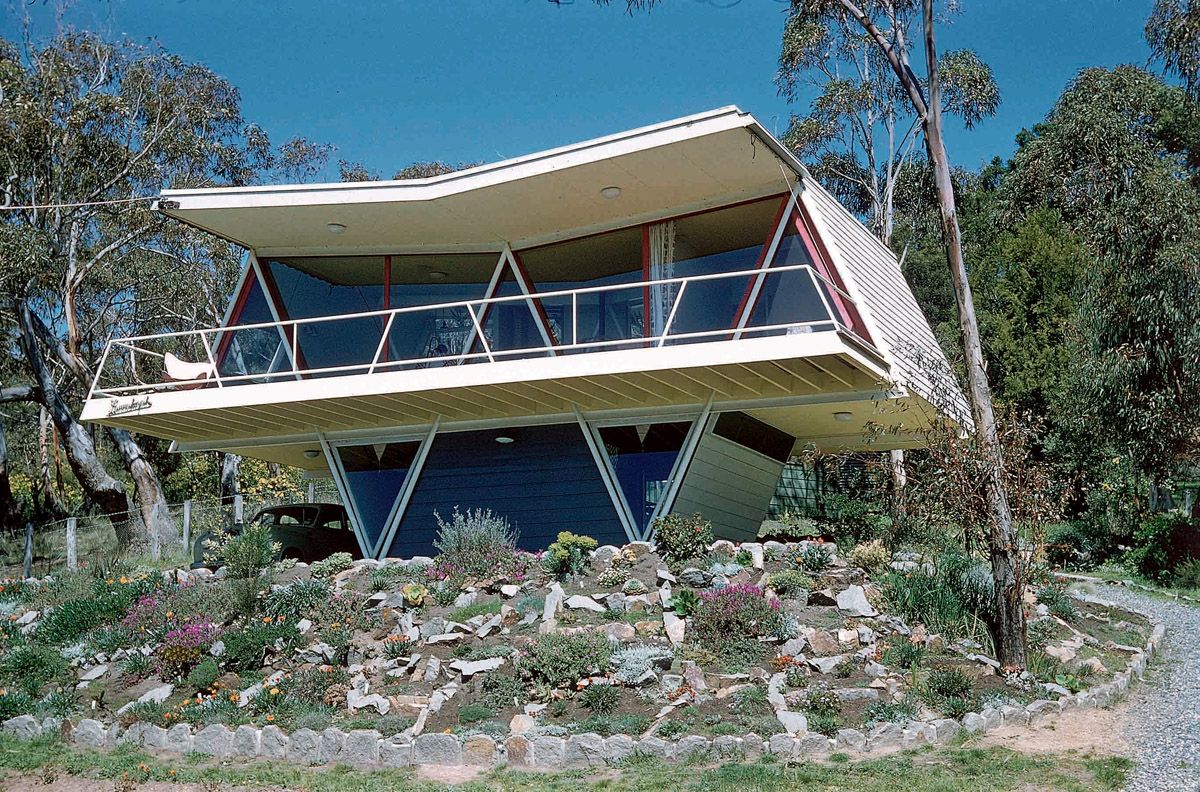

McCraith House by Chancellor and Patrick (1958). Courtesy of the McCraith family.

The exhibition that tells us this story of identity and desire is politely arranged in chronological order and a narrative of form emerges. It would appear that the way to an Australian identity is via a thorough experimentation with new form and a flavoured vernacular through the employment of local materials, not to mention an abundance of fine views. The new lifestyle gives rise to open, horizontal and dynamic L-shaped plans. Then there is the radical shift to the flat roof form with “thrusting eaves”, and later the institutional experiments with monumental closed form, and the many pavilion forms, with and without shallow pitched roofs, along the way.

The framed drawings, which are sometimes mere butterpaper scraps retrieved from the archive, are evidence of architectural work masterfully handled. It is clear that the architects have studied their predecessors with great care and respect, and that their own vision has matured during the history of their practice. The exhibition hierarchy favours the framed drawings, which are then offered secondary support by foam-mounted photographs that document the final built products and associated paraphernalia – here the face of a client, elsewhere a magnificent view.

On an interactive screen of sorts, visitors can peruse postcard snapshots of works by Chancellor and Patrick, intermixed with historical contextual images. In the midst of depictions of a Melbourne preparing for the 1956 Olympic Games, houses under construction, a range of cars pulled up in driveways and “car shelters” as evidence of the nation’s great love for the automobile, there also appear convivial images from the “Peninsula boys” – for instance, a lunchtime game of chess to prove the intellectual mettle of the office. Suddenly, light is shed on the image of David Chancellor. He wears a calm expression and appears to be standing beside a drawing board. The workspace is flooded with sunlight.

What is unusual is that he appears to be wearing a drawing smock of some kind. This is strikingly familiar; it could be a scene from the Bauhaus – maybe it mirrors a faded, iconic photograph of Moholy-Nagy? Unfortunately, no Google Image search will confirm my suspicion. The identity that can be seen to unfold at first is highly indebted to Europe, but necessarily skewed through the interpretative lenses of the land down under. The hearth is still the representative space around which the family gathers, as womenfolk hover beside the elbows of their husbands. Slowly, as the fifties approach the sixties, there are signs of the disappearance of the hearth and the emergence of the feature wall and another kind of sensibility.

One telling newspaper advertisement, which clearly signifies the new joy of the larrikin and mongrel identity that Australians will grudgingly come to love, depicts two men with snorkels and goggles squeezing into their flippers against the backdrop of a living room feature wall, presumably composed of local stone. The handmaiden beside them is not only showing her knees and wearing no stockings, but is dressed in a beach playsuit!

ES&A Bank, Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, by Chancellor and Patrick (1958). Ritter-Jeppesen Studios, Melbourne. Chancellor and Patrick archives.

Laborious research has been undertaken to present the exhibition and much of the debt is owed to the principal curator, Winsome Callister, whose Monash University PhD was based on the architecture of Chancellor and Patrick. Of merit also is the associated program of lectures, with an emphasis on hearing from some of today’s well-known women architects, such as Maggie Edmond of Edmond and Corrigan, who in 2001 designed an extension and renovation for Chancellor and Patrick’s Cameron House in Flinders (1961); also Debbie-Lyn Ryan, of McBride Charles Ryan, famous for the Klein Bottle House. What is finally confirmed is an ongoing and resolute fascination with formal experimentation that persists today, a desire for new form as though this will be the way to confirm the Australian identity. But will formal experimentation suffice to save us?

Source

Discussion

Published online: 5 Jul 2011

Words:

Hélène Frichot

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2011