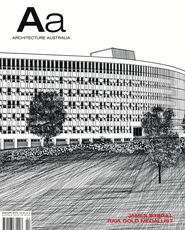

Landscape or giant animal, Undulant ’s shaggy green folds represent “Nature” within the restrained space of the waiting room.

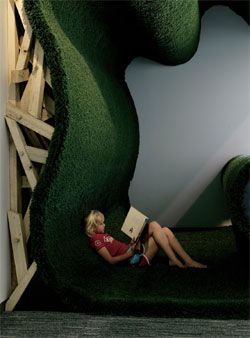

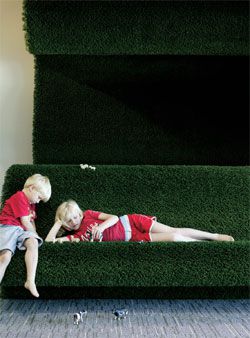

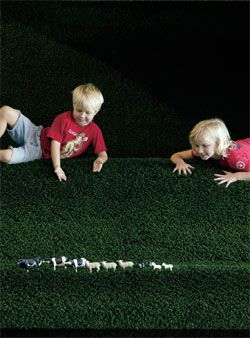

Undulant is particularly child-friendly. The bench seat can be climbed on; the cave can be lounged in comfortably.

Undulant is such a beautiful word. Its generous vowels so aptly match the wave-like motion it describes with a lulling, torpid comfort. Undulant qualifies the form of a surface, beneath which something perhaps more mysterious is at play. Its fluid nature is capable of unpredictable, even monstrous change and holds below its surface our fear of the unseen. The gentleness of form belies an inherent sense of discomfort, and it is from this perspective that I propose to consider the latest collaboration between architect Alice Hampson and artist Sebastian Di Mauro.

Undulant is a public art installation for the entry foyer of the child and maternal health and welfare centre in the sprawling city suburb of Logan. It was commissioned under the Queensland Government’s Art Built-in programme, which allocates two per cent of the funding of all new government buildings (except prisons) for the commission of public artworks. Hampson and Di Mauro sought to physically engage both children and adults with this work and to generate a dynamic and memorable set of poetic, spatial and social relationships within its modest waiting room setting. Undulant establishes a dialectical conversation with its context as a primary conceptual tactic: it is giant-sized rather than precious, a section rather than a discrete object, curved and hairy instead of rectilinear and smooth. The section, itself an abstraction of the Australian coastline, is used to extrude an imaginary landscape of lush folds from a surface of artificial grass (Wimbledon Unreal®). The human body is recognizable in this abstracted section through the introduction of a giant bench seat and the archetypal presence of a cave. It is this familiar unfamiliarity which allows the work to absorb multiple roles and to incorporate a certain functionality without losing its qualities of uncanny abstraction.

Dis comfort is a condition of Undulant . As a public artwork, it is designed to invite interaction. To take the analogy of the ocean, one can choose to observe its gentle folds or to journey on its surface at the risk of becoming queasy. I was intrigued by a palpable queasiness, a slight discomfort, in the public reception of the work. This reaction is testimony to the pertinence of its conceptual strategies – there is perhaps nothing worse for an artist than an indifferent audience. Discomfort forces a physical and emotional acknowledgment of the location of the body in space. Undulant compels its public to observe the present and to be conscious of the immediate physical environment.

The waiting room is a perceptually invisible space – one that anthropologist Marc Augé groups in the same category as the airport or the supermarket: a non-place. 1 Augé describes the non-place as “the collective without the celebration and solitude without the isolation”. The plastic chair of the waiting room is particularly significant in this light. Codes of representation underpin the perceptual invisibility of non-places and are matched by codes of behaviour ensuring personal anonymity. The visitor is presented with a choice upon entering the new community health centre. To the left one may be seated on a plastic chair and to the right on a giant astroturf bench. Individualized space is contrasted with collective surface and the visitor must choose between viewing and being on view. Undulant creates theatre by subverting the social interactions of the non-place and inverting its power as adult realm. Children climbing on plastic chairs are misbehaving, whereas children straddling hairy benches are having fun. This play on functionality transforms the waiting room, and the act of waiting, into aesthetic experience.

Undulant is primarily a representation of “Nature” within the confines of a hospital interior. This is nothing new. Nature is generally understood to be calming and most waiting rooms contain it in some form, whether a sad pot plant or a photograph of a forest. The originality of this work derives from its violent disruption of the codes of the invisible representation of the non-place. This green, organic form can be understood as a landscape or a giant animal brought indoors. Paradoxically, an artificial nature becomes within this space unruly, disruptive and unhygienically hairy. Discomfort is, however, individually experienced and depends on one’s point of view. In this instance the perception of the child differs fundamentally from that of the adult. Children understand the language of this work. Grass is a friendly surface for a child, animals are to be touched and caves are spaces in which to imagine and play. Diametrically opposed was the reception of the work by the director of the centre, for whom there was decidedly too much Nature represented in his waiting room. Hairiness is generally unwelcome in a medical environment and Undulant has particularly long hair. Lawrence Toaldo of Conrad and Gargett Architects, the Art Built-in project manager, is reported to have tackled the aftermath of the unveiling with consummate tact.

Percent for art schemes have existed in many parts of the world since the late 1960s. Tasmania was the first state in Australia to implement such a scheme in 1980, followed by Western Australia (1989) and Queensland (1999). In addition to state government programmes, there has been a substantial investment in public art throughout Australia by city councils, development corporations and the private sector. Public art is a slippery term. Where do the boundaries lie between art and architecture, design and decoration? Turf wars and aesthetic discourse aside, does public art have a public? At the risk of becoming just another form of space junk, there is a pressing need in the public arts for frank and critical debate among the many parties involved on both the processes and the outcomes of these policies.

Undulant is a powerful and lyrical work for which Hampson and Di Mauro should be commended.

1. Marc Augé , Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity , translated by John Howe (London: Verso, 1995) .

Credits

- Project

- Undulant

- Project Team

- Lawrence Toaldo, Thomas Justice, Ben Tait, Mat Tobin

- Architect

- Conrad Gargett

Australia

- Consultants

-

Artist

Alice Hampson in collaboration with Sebastian Di Mauro

Fabrication Urban Art Projects

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Type Installations