Peter Wilson, 2013 Gold Medallist.

Flattered as I am to be the recipient of the Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal, I feel a certain obligation to explain my lack of visibility in Australia, although I understand this is not the case in terms of media visibility.

The fact is that I drifted overseas at the age of twenty-one for a year out, one that has now extended to forty years. Even after ten years it was obvious that my personal and professional commitments in the European forum had gotten hold of me. I was at that time a very young Diploma Unit Master at London’s Architectural Association, as were Zaha Hadid and the whole team of chums and rivals assembled by what Peter Cook referred to as “that wily old fox,” the Architectural Association chairman, Alvin Boyarsky. In fact, Peter, Zaha and I were all keynote speakers at an Australian Institute of Architects conference in Adelaide in the late 1970s, where our hosts took the liberty of hiring a stand-up comedian to lampoon us “paper architects.” The Adelaide audience found it mirthful in the extreme for Zaha to be referred to as “Zaza” and me as “Peter Will-soon” (I hope that old clown is now rotating in his grave).

How was it that we came to build buildings in many European countries? The answer is quite simple – the European competition system. This, our principal form of procurement, is also our principal form of research and we have accumulated over the years an archive of some two hundred zombies, designs that did not win and yet cannot be buried. I regularly hold seances with this archive of experiments, most of which are, due to the excessive hours they involved, embossed on and dear to one’s heart. A clever shrink could make a healthy living treating the trauma of unsuccessful architectural competitions; at the same time overpaid lawyers laugh their heads off at architects who spend so much time on unpaid work. We once in a fit of scientific office control calculated that we needed to win at least one in five to keep our heads above water. Even then only 50 percent of first prizes get built. Yet this is still a good system, one that delivers, or should deliver, architectural quality for many private institutions and all public buildings – schools, universities, government offices and so on – especially when, as is the case in Germany, 10 percent of participants must be young architects (a selection procedure that is now regulated by European law).

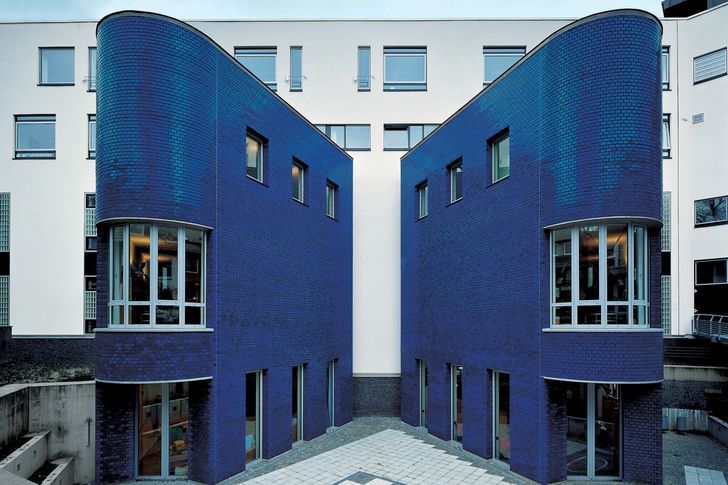

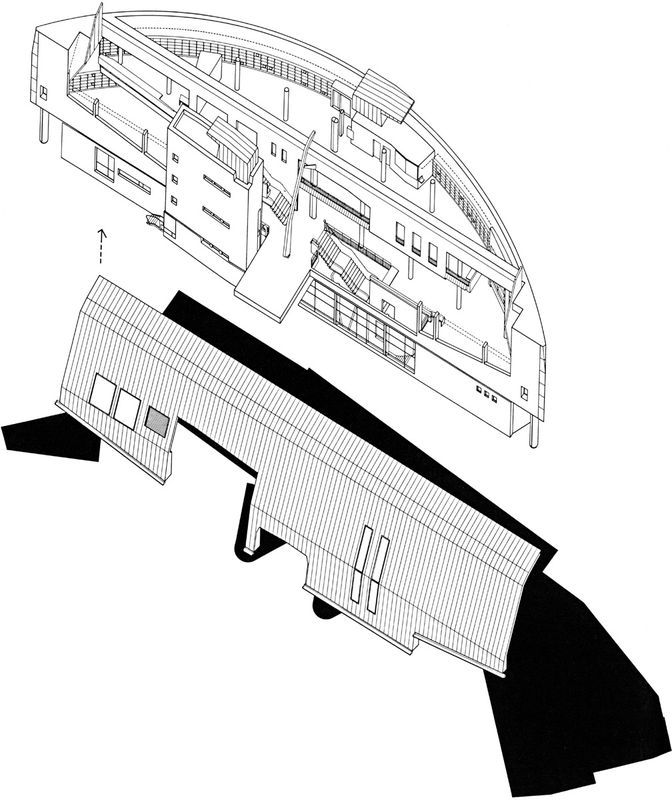

New City Library, Münster, Germany, 1993.

Image: Julia Cawley

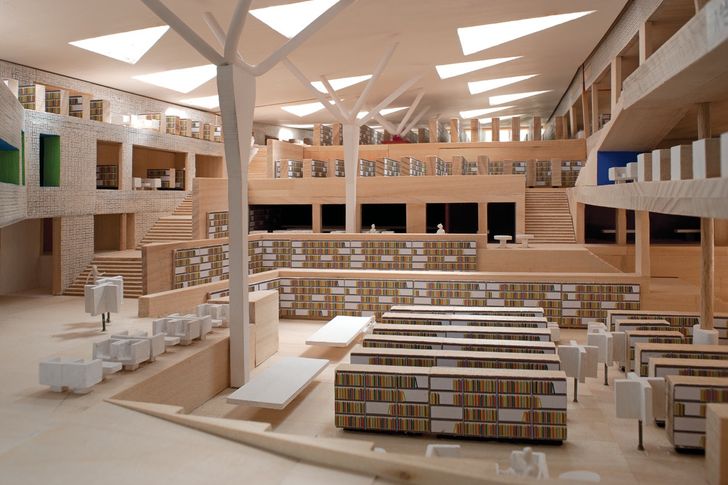

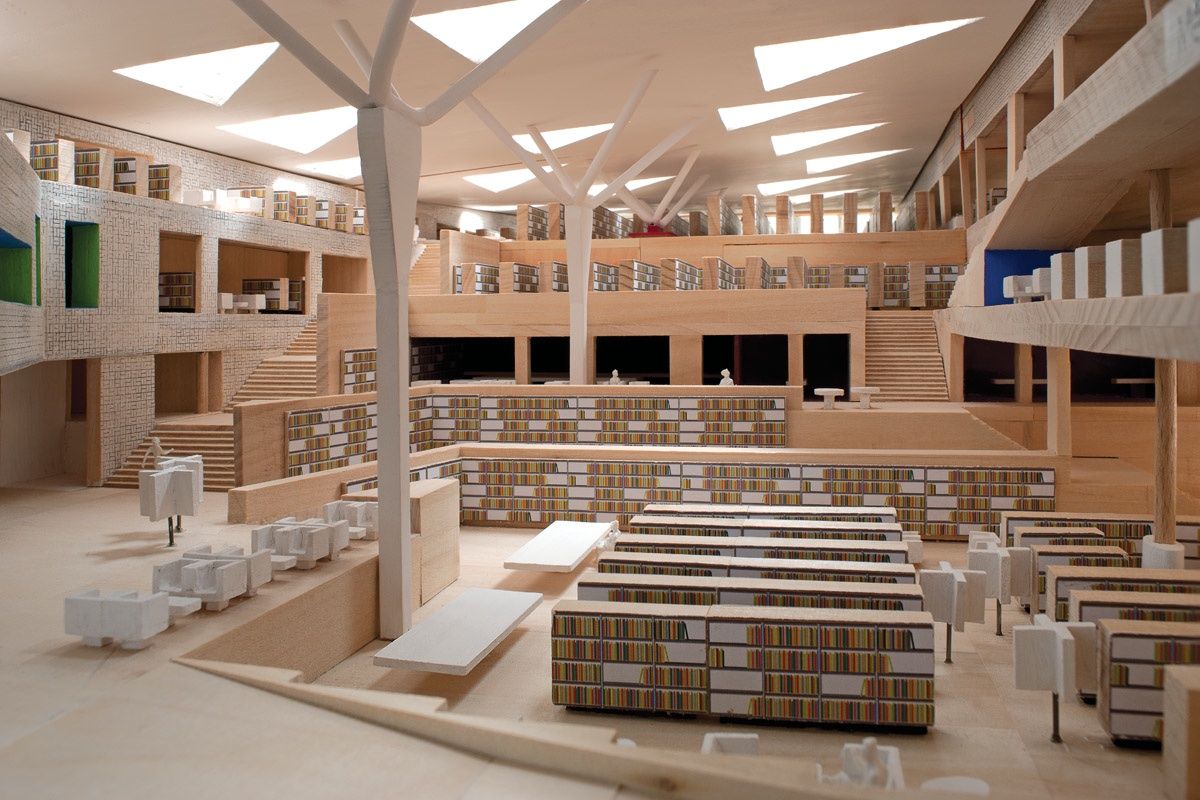

Bolles + Wilson made the transition from academics to building architects with our early win of the Münster City Library competition. This remains our flagship, and after twenty years remains also at the top of the ranking list of more than seventy public libraries in Germany. With this project, heavily influenced by Asplund and Scharoun, we taught ourselves to detail, or, as the German establishment never tires of saying, to make a meal of detailing. Gerard Reinmuth once suggested that after this project we went straight, adapting to circumstance (or perhaps budget). There certainly is an acquiescence to rule systems that one acquires (and even enjoys) in a middle-European context (I spend my evenings grappling with the differences between Kantian logic and Mr Burke’s sublime). We are right now just back from a workshop in Venice, one dominated by the residue of a German/Italian rationalist axis (Ungers and Rossi), who regard us with our Anglo-Saxon pragmatism and playful Architectural Association background as wilful heretics, dammed souls. Ten years ago this did not stop us winning the BEIC Library competition in Milan and taking it on as general planners, also responsible for subcontracting a full team of native consultants. Complete documentation is still waiting on a shelf in Milan for Italian politics to find the right gear.

BEIC (European Library for Information and Culture), Milan, Italy by Bolles + Wilson. Invited competition 2001. Awarded first prize. Planning phase 2004–2013.

Image: Bolles + Wilson

In the meantime we have been happily librarying away, with a city library in the Dutch provincial town of Helmond (not a competition win but the result of a selection procedure that called for a vision – the Dutch way around European competition law), and also the German Library of the Year prize for a very small (one-room) library we built, again in Münster. This was in the local prison, built by prisoners, costed by criminal businessmen and responsible for a significant behavioural shift among prisoners. Reading has now replaced TV watching as their principal activity. Embodied in this little work is what we regard as one of architecture’s principal roles – a form of social engagement – a belief that spatial quality and generosity can affect everyday lives. In fact my partner Julia Bolles-Wilson has now with her students designed a further fifteen prison libraries. Their implementation on minimal budgets has caused a veritable reading revolution among inmates in this part of the world (prisoners prefer travel books to detective novels).

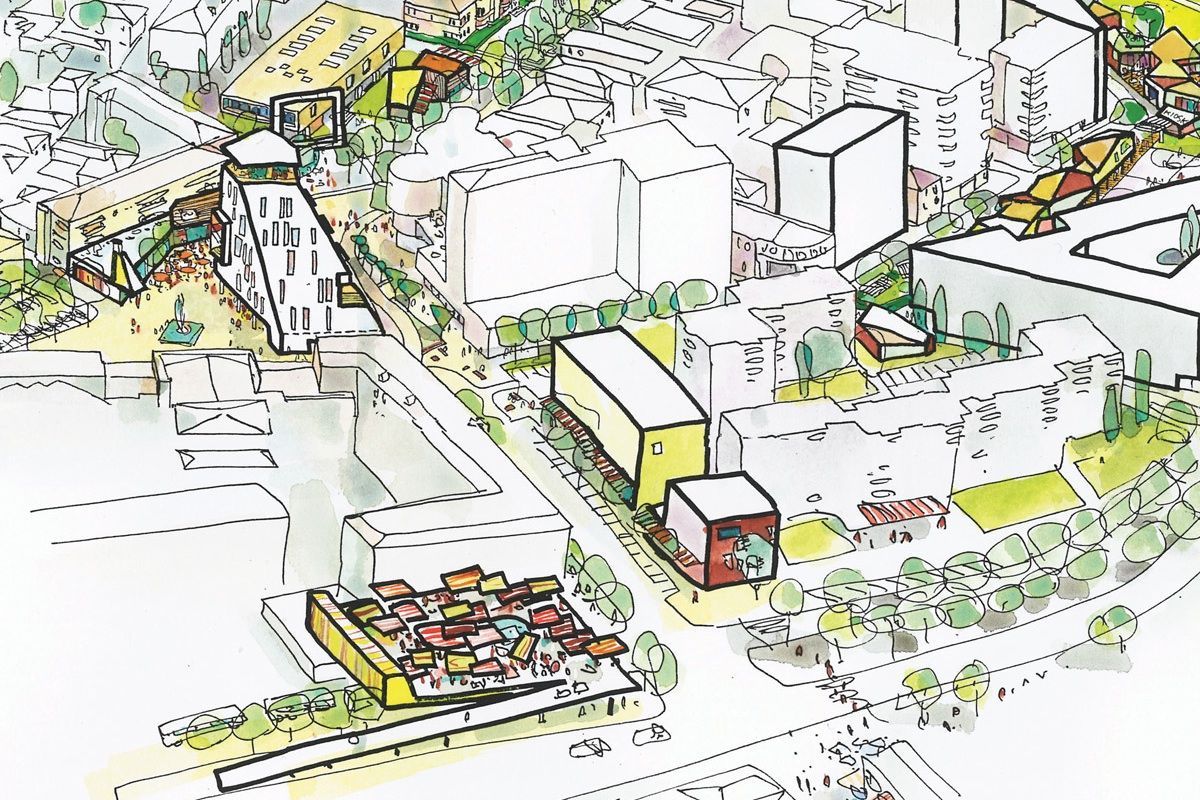

Scenographic urbanism – masterplan for Pilgrim Street Newcastle, 2007.

Image: Bolles + Wilson

It sounds as if we spend all our time working on or in libraries, and it must be said that the library, even in the age of the ebook, remains one of the few truly public building typologies (unlike the rest of today’s mono-functional city centres, dedicated as they are to exploitative commerce). I was recently chairing a competition jury in Medellin, Colombia, where a program of public libraries has in the last few years been instrumental in transforming the most dangerous neighbourhoods of the world’s most dangerous city into well-functioning communities. It is an example we can all learn from, an uplifting moment when architecture becomes the catalyst for social change. I would here ask the question, where in an Australian context might be the cracks for this type of intervention, for an optimistic rescripting? In Rome there are more than a thousand community garden projects, both official and informal, upgrading derelict public space.

HouseP, MÜnster, Germany, 2012 by Bolles + Wilson.

Image: Christian Richters

This would probably be the place to do some high-minded sermonizing on the subject of sustainability, a subject that right now has the moral upper hand – quite rightly. It takes a lot of head bashing to bring about a paradigm shift in the popular imagination. But if anyone out there has not yet grasped the necessity of sustainable thinking I doubt if I will be able to convince. The question inevitably arises, what is it that we are sustaining? Our irresponsible, selfish and excessive consumption habits, or even our pathological mobility? In a European context, sustainability is boiled down to the amount of energy consumed in the construction and the life of a building. The zero-energy house is bandied about as the right medicine for our bad conscience as good consumers. What does this involve? In cold climates, an overcoat of twenty to thirty centimetres insulation and triple-glazed windows that do not open. Air for breathing comes from modest mechanical ducts. This is the official European Union policy for the passive house, the adoption of which can lead to all sorts of subsidies and tax gains. There is, though, among architects and specialists a growing body of dissent pointing out that the official energy philosophy is the result of successful lobbying in Brussels by the insulation industry. Heavily insulated buildings are also airtight, which leads to problems of condensation and hostile mould cultures. The alternative is thick walls of adobe, which breathes. We have recently completed one of our rare suburban villas. The walls are fifty-centimetre-thick Poroton, a lightweight, high-thermal-insulating clay brick. It also breathes and absorbs humidity.

BnL (Bibliothèque Nationale de Luxembourg), international competition entry by Bolles + Wilson. Awarded first prize in 2003. Construction to commence 2014.

Image: Tomasz Samek

For our current large library project, the National Library of Luxembourg, our clients the Administration des bâtiments publics (office of public works) took the brave decision to ignore the official Brussels philosophy for sustainability and to go one better with a low-tech, low-energy concept – thick walls utilizing thermal mass, natural ventilation with night purging and, at the core of the building, the national archive, which maintains a constant 18 degrees due to its bunker-like layered walls (but no airconditioning).

I would like to dispel any implication that I as an Australian operating in Europe might be a sort of cross between the architect hero of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead manifesto and a narrative-spinning Banjo Paterson (even if our narratives now play out on a phenomenological level). The primacy of the individual as architect or Silicon Valley winner has been recently and powerfully debunked by cult filmmaker Adam Curtis. The thesis of his mesmerizing BBC film All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace (watch it) is that computers have failed to liberate humanity, that the internet commodifies personality, also that there is no such thing as a stable cybernetic self-organizing system (the hypothesis of ecology). Curtis’s debunking method is based on the idea that as long as you are intellectually clear about what you are saying, you can be as silly and as emotional as you like. While Curtis’s media sampling style is close to avant-garde film techniques, he does atmospherically capture significant moods that move through society, something that one would hope architecture also capable of doing. It is a question of taking responsibility for the built environment, first understanding the deep structures it embodies and then developing techniques to reformat it. In this sense we at Bolles + Wilson have developed what we term a scenographic urbanism – visual scenarios that seek a way around the box ticking and report writing that today encumbers and incapacitates urban design.

Source

People

Published online: 17 Dec 2013

Words:

Peter Wilson

Images:

Bolles + Wilson,

Christian Richters,

Christian Richters,

Julia Cawley,

Tomasz Samek

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2013