How many urbanisms are there now? New urbanism, generic urbanism, bingo urbanism, landscape urbanism, ecological urbanism, splintered urbanism, superlative urbanism, guerilla urbanism, green urbanism, polycentric urbanism, integral urbanism … and now “distributed urbanism”! What all these isms indicate is that the rapid urbanization of the world’s population is not only topical, but perplexing. And that’s probably how it should be because if there is one thing we’ve learned from twentieth-century urban planning it is that cities defy reduction.

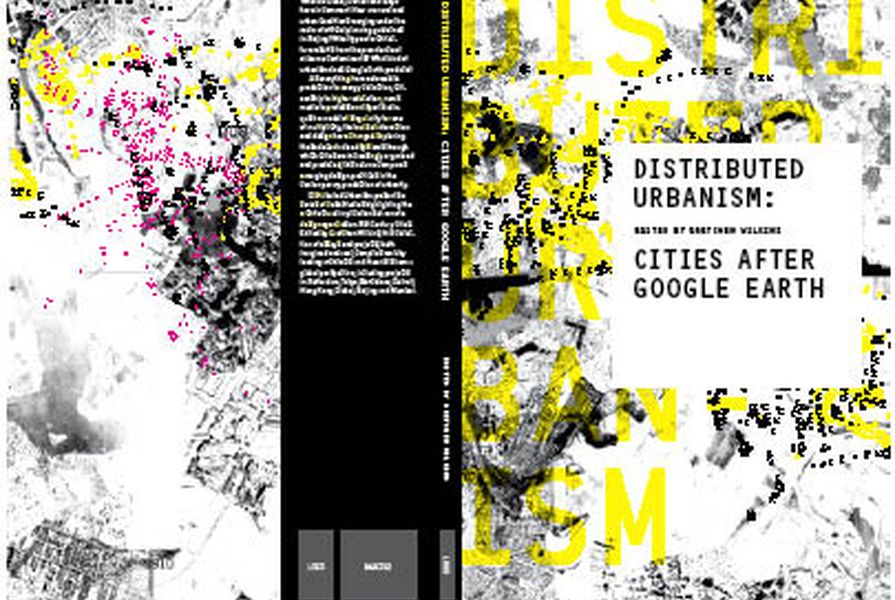

Distributed Urbanism is a small collection of essays about contemporary cities edited by Gretchen Wilkins, an architect based at RMIT. The term “distributed urbanism” is not clearly defined but it seems to mean that contemporary systems (communications, logistics, etc.) are – by virtue of technology – no longer centralized but distributed across global space and increasingly democratically interfaced. The premise of the book is that as a consequence of this technological dispersal we are experiencing new forms of urbanity and these new forms require new descriptions. As Wilkins says in her short and somewhat scatty introductory essay, the ultimate purpose of this book is to “identify the agents of change in contemporary cities and speculate on the role these agents have in architectural practice.” Easy to say …

The subtext to Distributed Urbanism, “after Google Earth,” adds to the enigma of the book but does little to help clarify its theoretical intentions. Ilka and Andreas Ruby do their best to honour the book’s title by situating the view from Google Earth in a broader account of twentieth-century urban visions. Ignasi Pérez Arnal, a professor of architecture in Barcelona, addresses the topic with a description of his research into using Google Earth and digital mechanisms to virtually generate instant urbanism in response to remote political and natural emergencies. Johan van Schaik and Simon Drysdale, both practising architects in Melbourne, record a chat they had about Google’s efficacy and its superficiality in relation to projects in the United Arab Emirates. The other contributors (“distributed” appropriately from Detroit to Dubai) really just head off in their own directions, in several cases making no effort whatsoever to address the editor’s agenda. For example, the landscape architectural duo of Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha from the University of Pennsylvania present work they have published elsewhere regarding their mapping of Mumbai, work that is as questionable in its relevance as it is beautiful in its graphic composition and politically correct in its posturing. But what the book lacks in synchronicity it makes up for with diversity.

There is an essay by Li Shiqiao about the aesthetics of cleanliness and sanitization in Hong Kong. Robert Mangurian and Mary-Ann Ray discuss unofficial settlements and urban agriculture in Chinese cities and Michael Speaks offers a select history of architecture in Rotterdam from 1979 to 2007. With three essays devoted to it, Detroit features prominently, but the essay by Jerry Herron, a professor of English and American studies and Detroit resident, is outstanding.

Wilkins has the last word in an essay titled Bubble Cities, where, all too briefly, she draws an axis from Dubai to Detroit. For me this is the crucial line in the book for it is along this axis that one will find the true nature of contemporary global urbanism. Declaring truth, defining what you really mean and honing towards accountable conclusions are, however, not what this book is about. What we get is a vague cartography of contemporary urbanism, a melange that for fear of reductionism renders the contemporary city more enigmatic than it really is. Distributed urbanism doesn’t do what it said it would and identify the forces behind appearances – indeed, for architecture the reflections are always better at an oblique angle.

For the foraging, free-range academic there is a lot of nuanced thought in this book, but the term “distributed urbanism” won’t catch on and at only a tad over two hundred pages, no-one will be banging the lectern with it. The book is a typical Routledge featherweight, one that wilts in the sun or subsides into the shadiest recesses of your shelf. But as weak as it might seem in the Darwinian struggle of contemporary publishing, this is precisely the sort of book that can contain the germs of new ideas - or at least new ways of approaching the old.

Gretchen Wilkins (ed), Routledge, 2010. Paperback, 208 pages. rrp $72.00; Hardback, 224 pages. rrp $247.00

Source

Discussion

Published online: 23 Feb 2011

Words:

Richard Weller

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2011